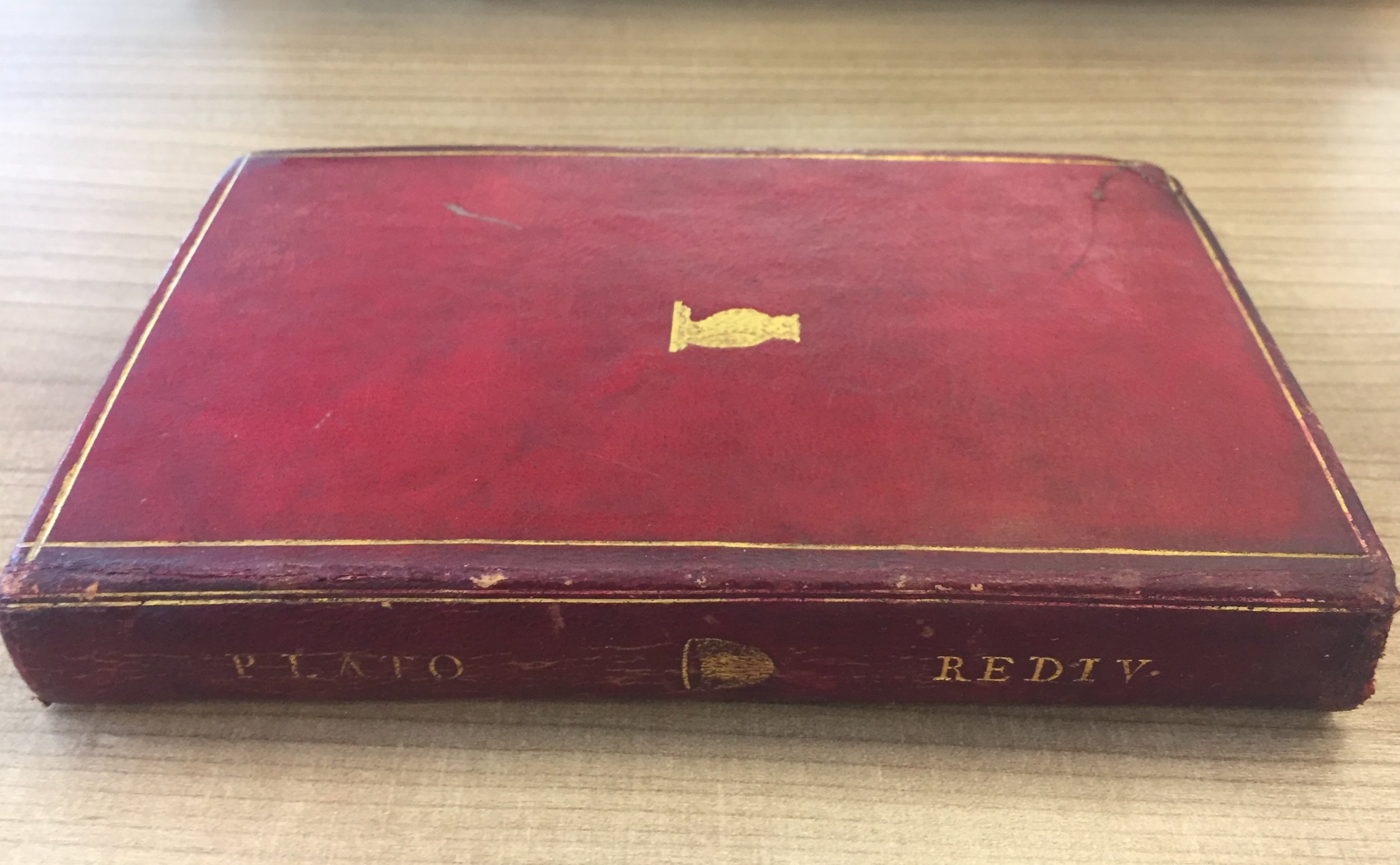

A shelf of books from the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, Germany. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

As an undergraduate I loved to scan the office shelves of the academics who taught me to see what books they owned. Later, I think the sight of my future husband's amazing collection of early modern books (stuffed into a small bedroom in a shared house in North London) was one of the things that attracted me to him. Part of this was of course library envy, but I think I always had a sense that the books a person displays on their shelves reveal something about who they are as a person.

The libraries of people from the past - especially scholars or political figures - can also provide insight into the influences on them and the development of their ideas. I currently have a PhD student who is reconstructing the library of King James VI and I, which is yielding fascinating information about his interests, contacts, and ways of working. Beyond royalty and the aristocracy it is rare to find much detailed information about the libraries of early modern figures. Some valuable reconstruction projects do exist. These include 'Hooke's Books' (https://hookesbooks.com), a database of books owned by the scientist Robert Hooke based on Bibliotheca Hookiana, the auction catalogue produced after he died, and incorporating other surviving books that bear marginal annotations by him. It is, of course, much rarer for the bulk of the books still to be held together, though we do have Samuel Pepys' Library at Magdalene College in Cambridge and Edward Stillingfleet's collection at the Marsh Library in Dublin.

Portrait of William Petyt holding a copy of Magna Carta (c.1690) by Richard van Bleek from the collection at the Tower of London. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

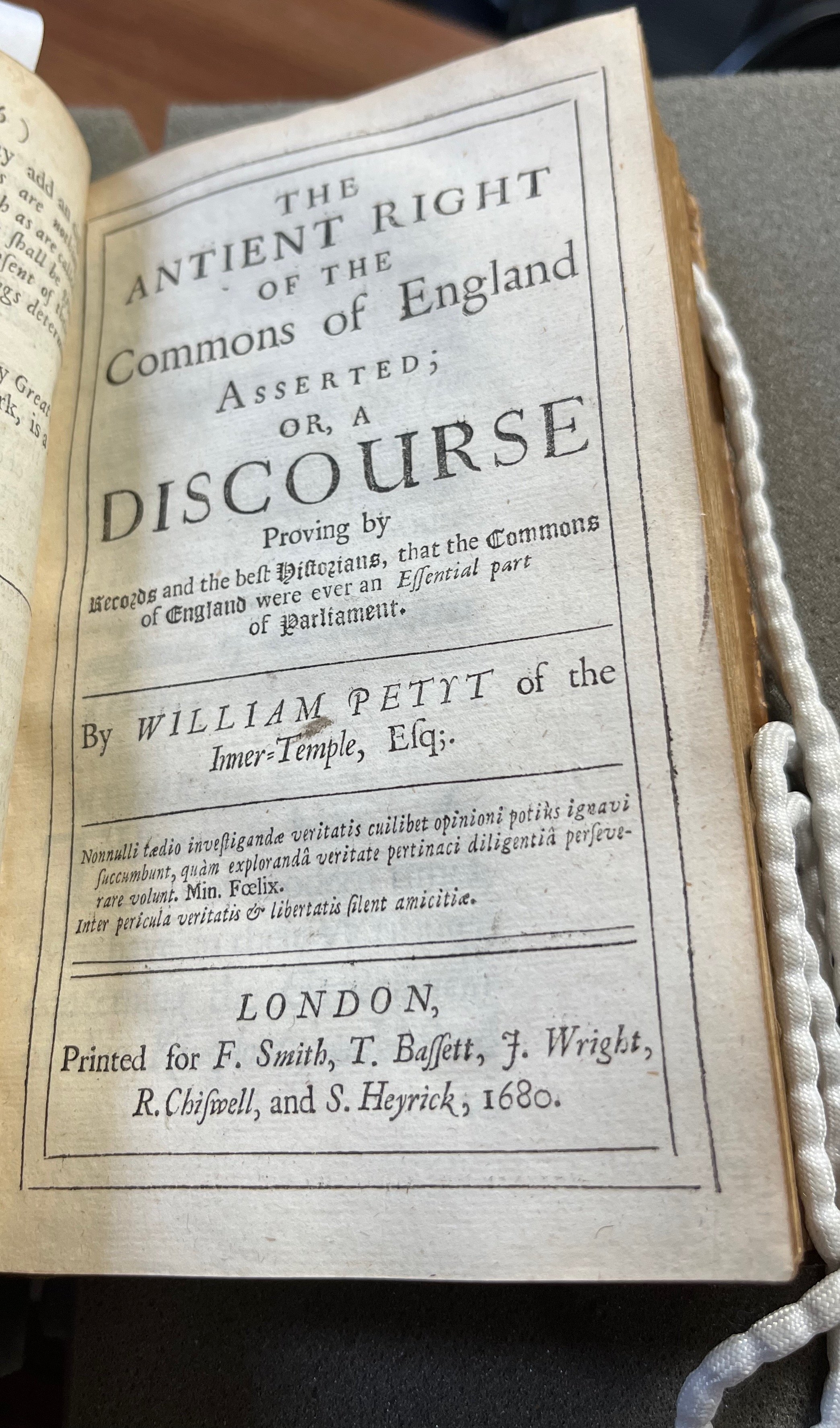

Consequently, the Petyt Library is a treasure for those interested in early modern books, scholarship, and reading habits. This library was transferred on long-term deposit from Skipton (where it had been held since the early eighteenth century) to the University of York in 2018. It is the library of not one but two individuals, the brothers Sylvester and William Petyt, both of whom were born and educated in Skipton before becoming lawyers in London. Sylvester became Principal of the Society of Barnards Inn in 1701. As well as being Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London between 1689 and his death in 1707, William was also the author of several works including The Antient Right of the Commons of England Asserted. Published in 1680 at the height of the Exclusion Crisis, this book justified the moves by Parliament to try to prevent James, Duke of York, from acceding to the throne on account of his Catholic beliefs.

Both men took care over what happened to their books. William requested in his will that his be preserved and kept 'safe and entire for publick use' (The National Archives: PROB 11/497/15). Some of his collection (in particular his manuscripts) went to the Inner Temple when he died and there is also a collection of pamphlets owned by him in the Middle Temple, but a number of his books were among those that Sylvester sent to Skipton.

William Petyt, The Antient Right of the Commons of England Asserted (London, 1680) in the volume Jane Anglorum facies nova, or, Several monuments of antiquity touching the great councils of the kingdom… Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle University. Special Collections: Bradshaw 342. 42 ATW. Reproduced with permission.

The library comprises approximately 4,600 books and pamphlets published between 1480 and 1716. As might be expected in a collection forged at this time, religious debates, political and legal controversies, and scientific treatises are all areas well-represented. The historical value of the collection is further enriched by the presence of a catalogue and manuscript notes telling the history of the library and its various movements. Having been sent to Skipton by Sylvester in the early eighteenth century, many of the books were housed in Skipton parish church. From there they were moved to the town's grammar school in 1881 and then to Skipton Public Library in the early twentieth century.

The Petyt Library offers valuable insight into the minds of these late seventeenth-century legal experts and the turbulent times through which they lived, and a revealing window onto the history of book ownership and libraries. Both aspects were reflected in the papers presented at the symposium held at the University of York on 20th June 2024. Yet, perhaps not surprisingly, thinking more deeply about the collection (as the excellent papers prompted us to do) tended to raise more questions than answers and to complicate rather than clarify. As Brian Cummings rightly commented in his closing remarks, there is a paradox in that the Petyt Library offers a wealth of material and yet it is difficult for us to make sense of it.

A central problem, hinted at in the introductory remarks by those at York who have been working with the Petyt Library and raised explicitly by Giles Mandelbrote in the first panel on early modern libraries and collecting practices, is whose library we have here. Not only does the collection now held at York include books that were once owned separately by William and Sylvester, but, as noted above, William's library was divided between the Inner and Middle Temple and Skipton. Moreover, the collection sent to Skipton was, at its origin, two libraries not one, since it was divided between the church and grammar school with the records suggesting that books were deliberately sent to one or the other.

There is also the question of purpose. Jessica Purdy noted that parish libraries are far from uniform, since they tend to reflect the aims and interests of the individuals who founded them. Moreover, there is a sharp distinction between a working library that was left in situ or to an institution after the owner's death, and an endowment library designed to suit the needs of those for whom it was constructed. In the case of the Petyt Library, the books sent to the grammar school do seem to have been primarily pedagogical but the origins and purpose of the books sent to the church may have been more complex.

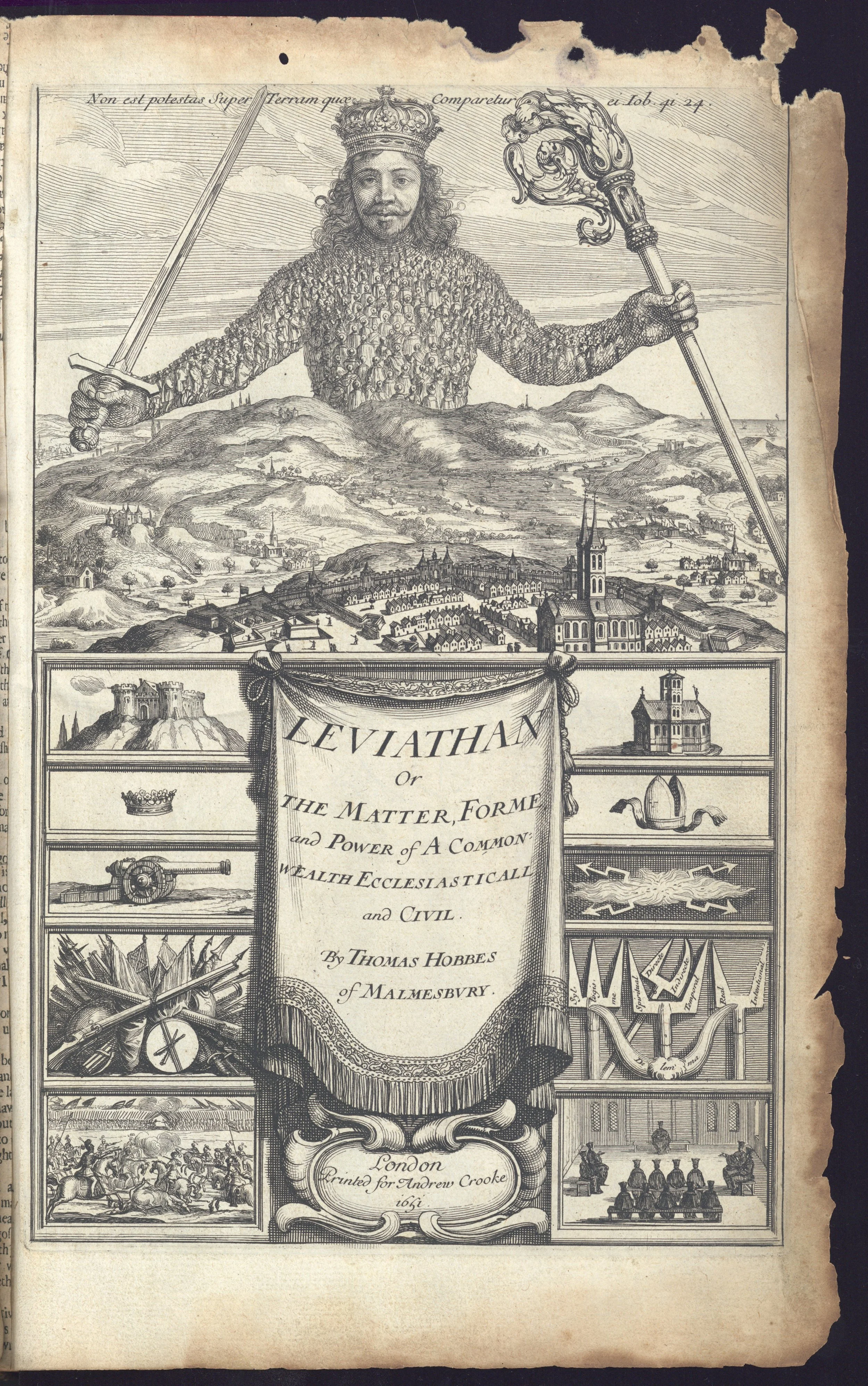

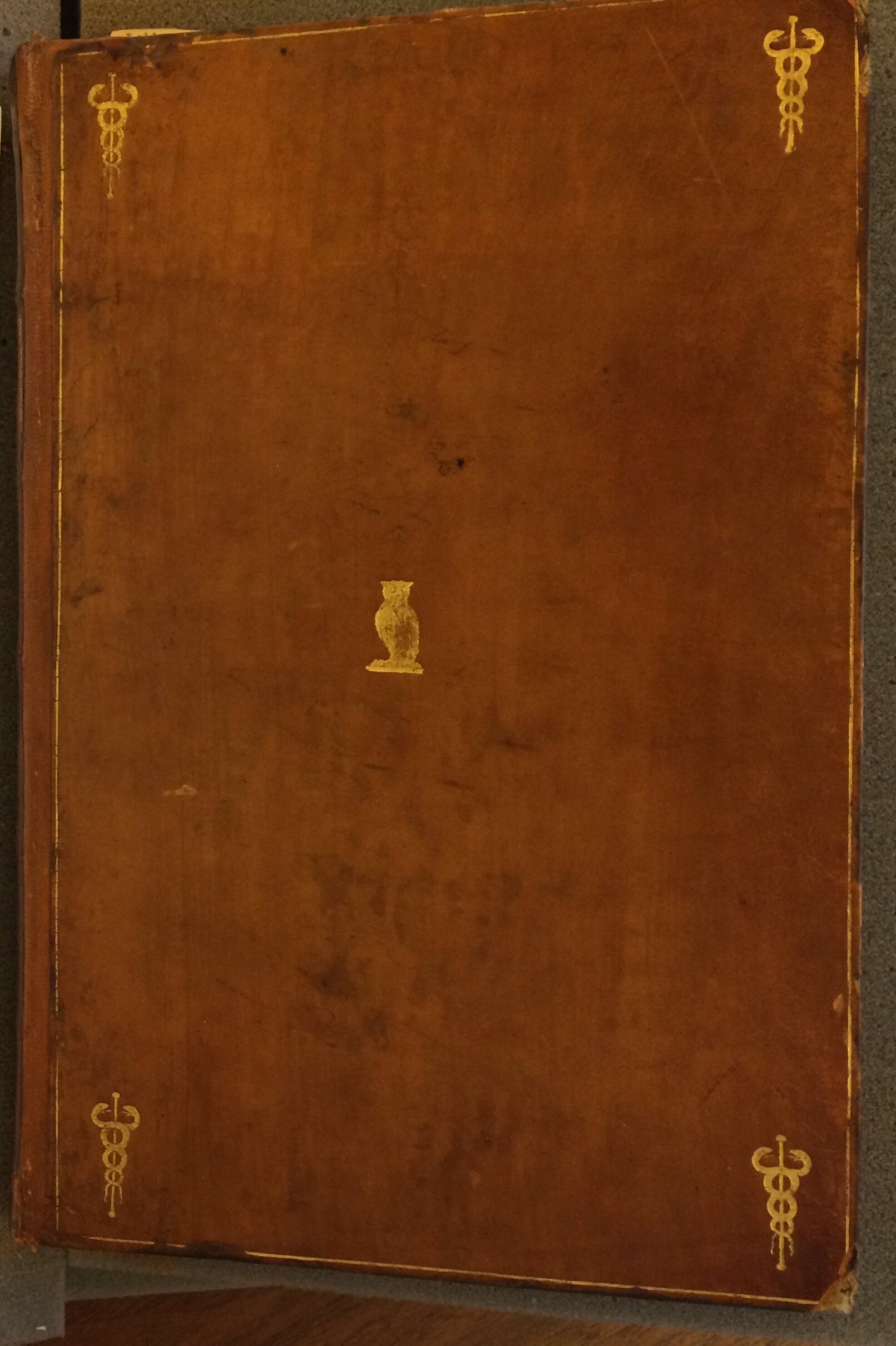

The Petyt Library also highlights the complex relationship between a library as a list or catalogue and as a collection of books. As Sarah Griffin discovered when the books started arriving at York, there are far more books in the collection than the catalogue suggested and yet, as Anouska Lester explained, 26% of the books in the catalogue are not now in the Library. Moreover, thanks to a major rebinding project in the 1950s, the books are no longer in their original bindings, and books that were originally bound together in Sammelband volumes have been separated (though Mark Jenner did offer the exciting prospect that it may be possible to reconstruct what was in them). The importance of seeing books as physical objects is something I have been exploring in my own research. I touched on this in my paper on the different approaches to the Exclusion Crisis reflected in the responses to Robert Filmer's Patriarcha written by William Petyt, Henry Neville, and James Tyrrell. Those approaches are evident not just in the distinctive use of vocabulary and sources, but also in the typeface deployed and the layout of the words on the page. Moreover, these elements complement - and in some case are even integral to - the arguments being made.

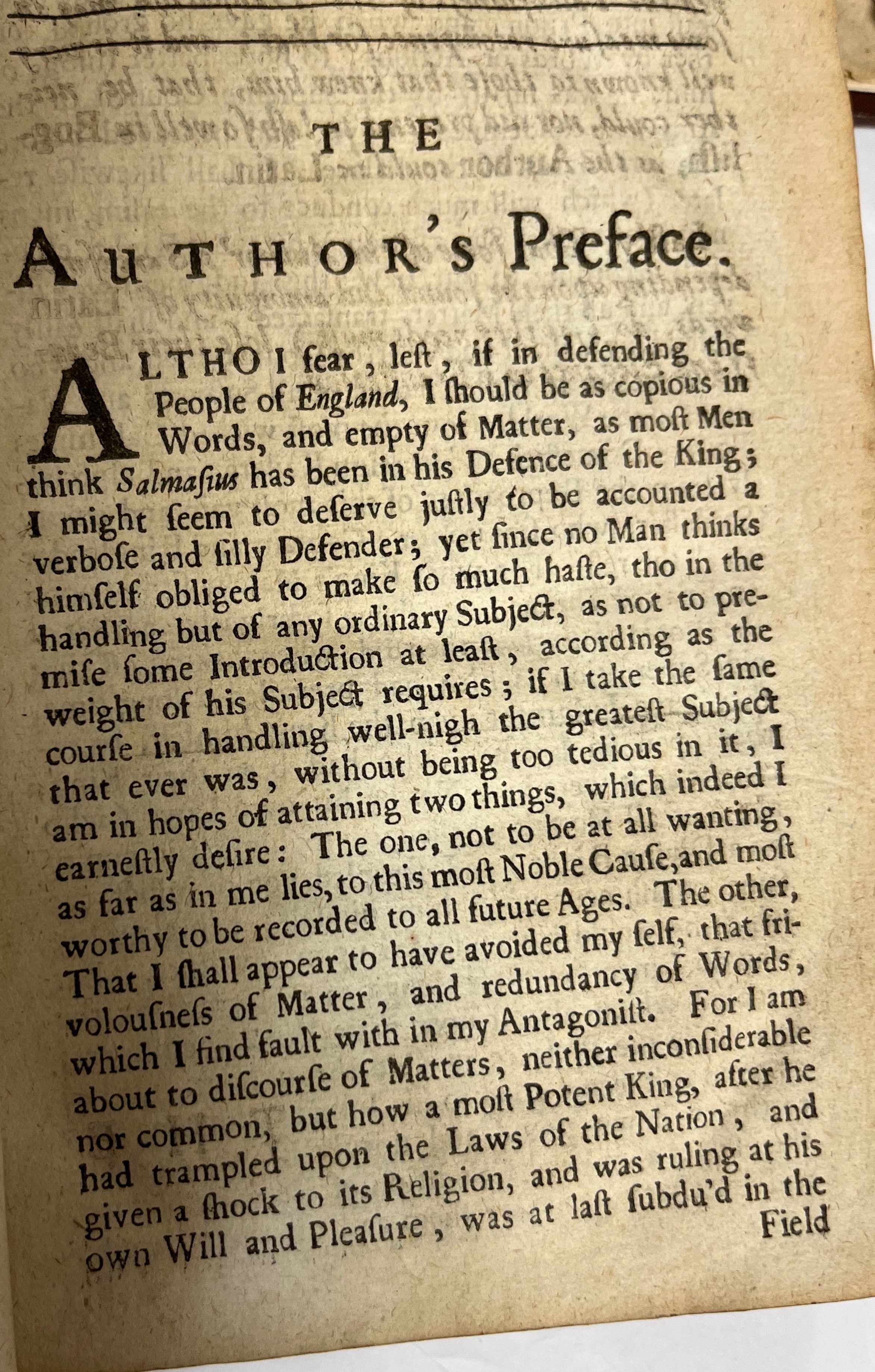

William Petyt, The Antient Right of the Commons of England Asserted, as above. This image shows one of the historical documents appended to the work.

The other set of reflections raised for me by the papers and subsequent discussion, centred on the themes of history and memory. In our panel, Mark Goldie and I explored the political languages deployed in the Exclusion Crisis debate. While the natural law approach - reflected in works by Tyrrell, John Locke, and Algernon Sidney - is often seen as having been dominant, William Petyt's more historically-minded approach, which drew on the language of the ancient constitution, was significant and influential at the time. History, and historical sources, lay at the heart of Petyt's argument (indeed he included copies of several historical documents at the end of The Antient Right). Mark reflected on Petyt's role in that volume as a keeper and curator of records - deciding and enacting which should be presented, how they should be interpreted, and which should be hidden from view. He noted that this mirrored both William's status as a collector of manuscripts himself - since there is evidence that he made them available to others - and his official position as Keeper of the Records in the Tower.

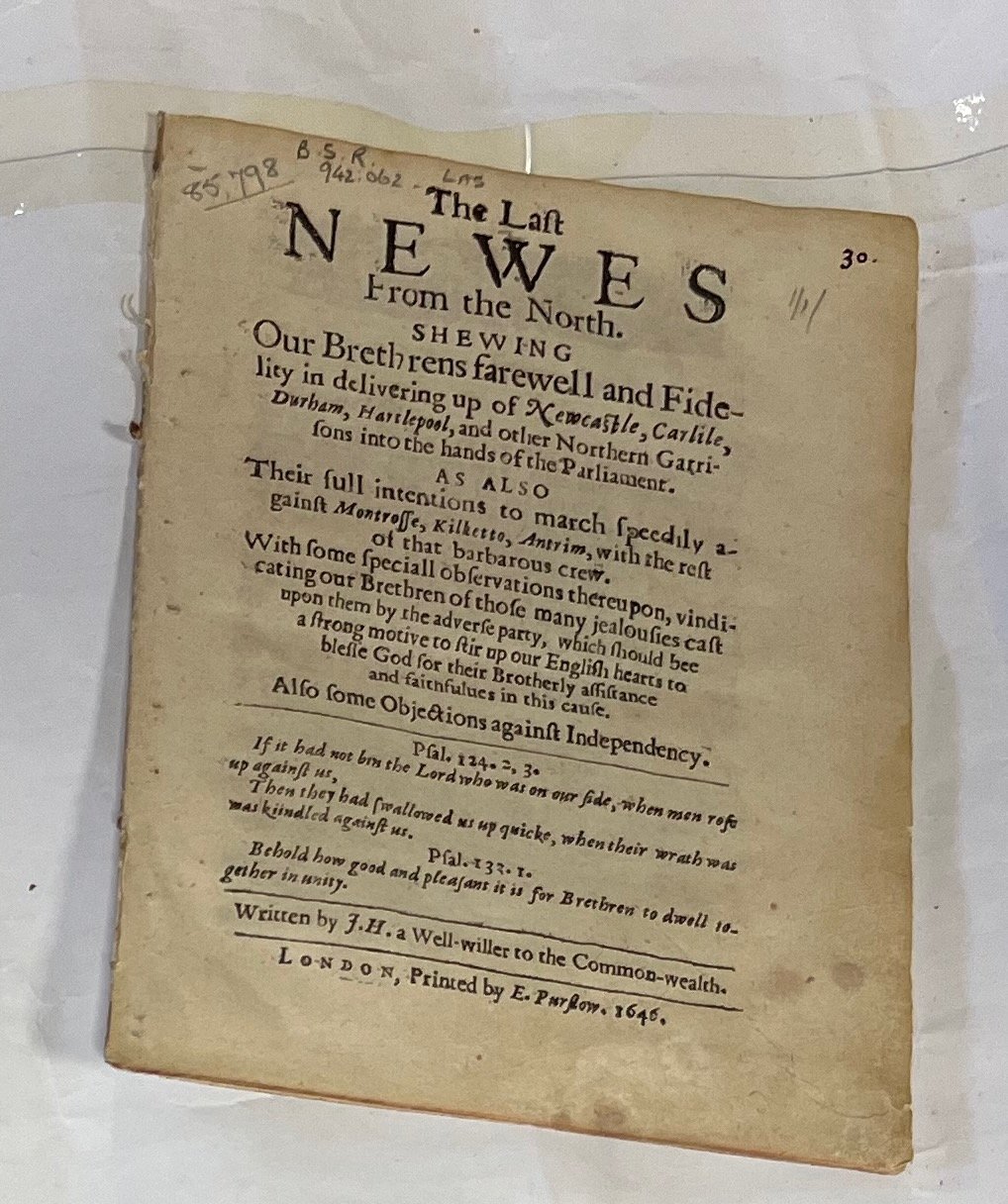

Curation determines not only history but also memory, and the question of memory and myth-making loomed large in the final panel as well as being raised explicitly by Laura Stewart in her closing remarks. The Petyt brothers grew up in Skipton during the Civil Wars. As Andy Hopper explained to us, Skipton Castle was a royalist garrison and saw much violence (including a siege in 1645 and the slighting of the castle in January 1649). These events left scars on the landscape, on buildings, and - as the Civil War Petitions project demonstrates - on local people. This gives significance to the large number of civil war pamphlets within the Petyt collection. Moreover, it was noted that just as Lady Anne Clifford's rebuilding of Skipton Castle, and her construction of a tomb to her ancestors in Skipton parish church, reflect her attempt to stamp her mark on the town (following a long legal battle to secure her property), so the Petyts' donation of the library was perhaps designed to serve as an equivalent or counterpoint to her acts of memorialisation.

There is another parallel, both Lady Anne and the Petyts used books and paintings as part of their memorialisation. Lady Anne's 'Great Picture' is a fascinating image that depicts her at different stages in her life, alongside carefully chosen books and portraits. This took me back to the case study that Hannah Jeans had presented to us at the beginning of the day. Among the manuscripts relating to the library, she explained, is a list of portraits that were sent alongside the books. It is not clear whether these were intended to be hung with the books, or even whether they were destined for the church or school. What the list does provide is a distinct sense of the circles in which the Petyts moved. It includes paintings of national figures, representatives from London's legal world, and leading figures from Skipton, and ends with portraits of the two brothers themselves. Significantly Lady Anne Clifford and her father George are included on the list, but not her uncle Francis nor her cousin Henry. The list, therefore, endorses her claim to the Skipton lands, and effectively erases her uncle and cousin from their title and history. As this suggests, history and memory are malleable and subject to reconstruction. In this context, documents and books are powerful tools and those who curate them, as the Petyts did, wield great power over what is remembered and what is consigned to oblivion.