Last month's blogpost centred on the radical periodicals produced by Thomas Spence and Daniel Isaac Eaton during the 1790s. This month I am extending that discussion by considering Spence's role as editor, and his use of his position to curate the words of others in such a way as to advance his own political ideas.

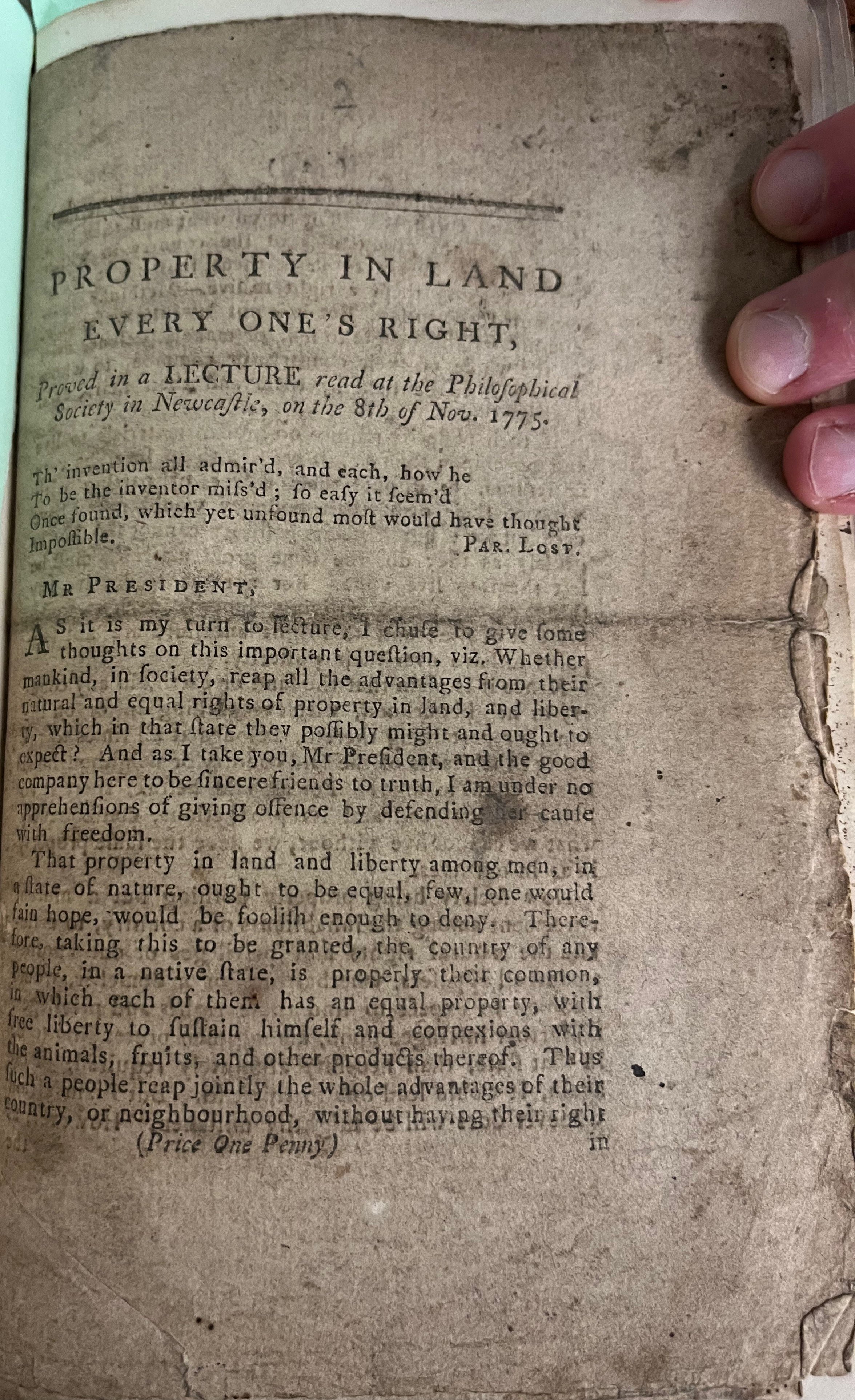

Spence’s Lecture, ‘Property in Land Every One’s Right’. From the collection of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne. Hedley Papers, Volume 1. Reproduced with kind permission.

Pig's Meat was composed almost entirely of extracts from a variety of political texts. Spence chose his extracts carefully, deliberately presenting key political themes. Prominent among these were: the importance of free speech and thought; the rights of man; and the superiority of republican over monarchical government. But Spence's main concern throughout was the oppression of the poor by the rich.

That theme also lay at the heart of Spence's Land Plan, which he first set out in a lecture to the Newcastle Philosophical Society on 8 November 1775. He argued that, in the state of nature, land was shared equally among all inhabitants for them to use to secure their own subsistence. On this basis, he insisted that 'the land or earth, in any country or neighbourhood, with everything in or on the same, or pertaining thereto, belongs at all times to the living inhabitants of the said country or neighbourhood in an equal manner' and that the state ought to protect this right to land (Thomas Spence, 'Property in Land Every One's Right'). In reality, however, land had been claimed by a few and divided among them for their own ends, making others dependent on them for subsistence. This injustice had been perpetuated through inheritance and purchase. Although this was the current state of affairs, Spence argued that things could be different if people were to acknowledge the injustice and take action. He suggested that each parish could form a corporation with the power to let, repair, or alter any part of the land, but without the power to sell the land. Individual inhabitants would pay rent to the parish for a portion of the land and those rents would be used to provide local and national amenities.

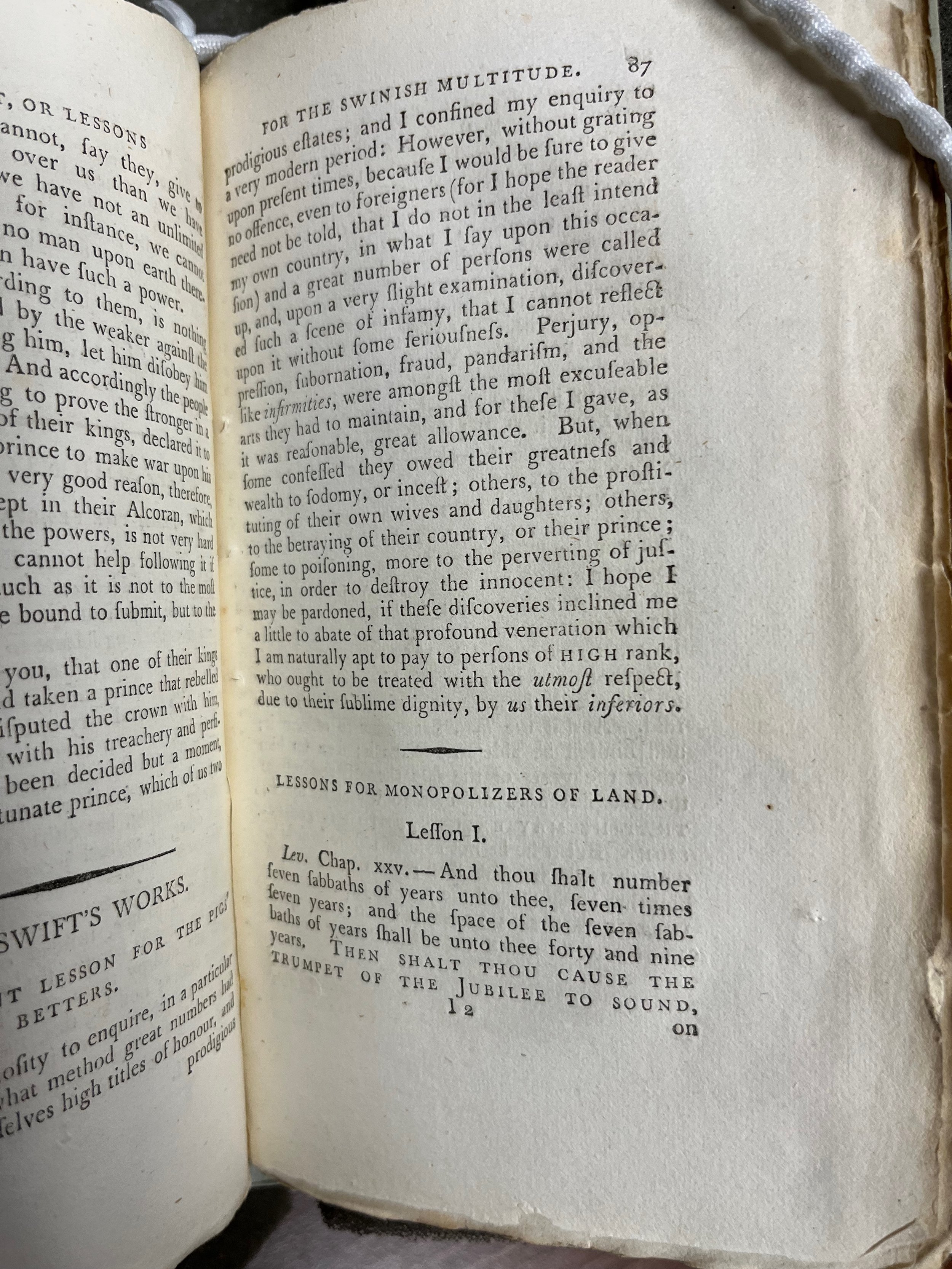

The section ‘Lessons for Monopolisers of Land’ from Thomas Spence, Pig’s Meat, Volume 1 (London, 1793). Robinson Library, Newcastle University. Rare Books RB 331.04 PIG. Reproduced with kind permission.

Throughout his lifetime, Spence produced a number of his own works (including political pamphlets, fictionalised utopias or travel writing, and even songs) which presented the key elements of his plan. The plan is also central to Pig's Meat, but here it is presented not in Spence's own words, but through those written by others. We can see how he does this by focusing on several extracts that appeared in the eighth issue (in autumn 1793). Under the title 'Lessons for Monopolisers of Land', Spence presents two biblical quotations. The first, which comes from Leviticus chapter 25, presents the Jewish idea of Jubilee. This required that every fifty years land within the state would be redistributed, reflecting the notion that the land belonged to God and was only granted to the people for their use. The second, which comes from Isaiah (chapter 5, verse 8), condemns those who parcel up land for themselves leaving none for others. These biblical passages are immediately preceded by an excerpt from the works of Jonathan Swift entitled 'An unpleasant lesson for the pigs' betters', which argues that those who enjoy wealth and power in society gained - and maintain - their position by vicious means, including incest, betrayal, poisoning, perjury and fraud. The biblical passages are then followed by an extract from the works of Samuel Pufendorf, to which Spence gives the title 'On Equality. From Puffendorf's Whole Duty of Man, according to the Law of Nature'. This passage includes the line: 'no man, who has not a peculiar right, ought to arrogate more to himself than he is ready to allow his fellows' (Thomas Spence, Pig's Meat, Volume 1, London, 1793, p. 91). Together, these passages reinforce key elements of Spence's Land Plan: that the land and the fruits thereof should benefit all members of society; that the current possessors of land have gained and maintained their position via unseemly means; and that it is possible (as in the example of Jubilee) to overthrow an unfair system.

Presenting what was a controversial plan via the words of others had obvious advantages for Spence, who was at this point an unknown London bookseller, recently arrived from Newcastle. Spence gives the impression that his Land Plan was in line with the views of serious political philosophers such as Pufendorf and respected authorities such as Swift. By labelling the Pufendorf extract 'On Equality' Spence was, of course, reinforcing this point. The inclusion of biblical quotations was another clever move. It simultaneously showed the poor that their cause was in line with the word of God (giving them greater confidence to assert their rights) and alerted wealthy elites to the fact that in oppressing the poor they were disobeying biblical injunctions and therefore God.

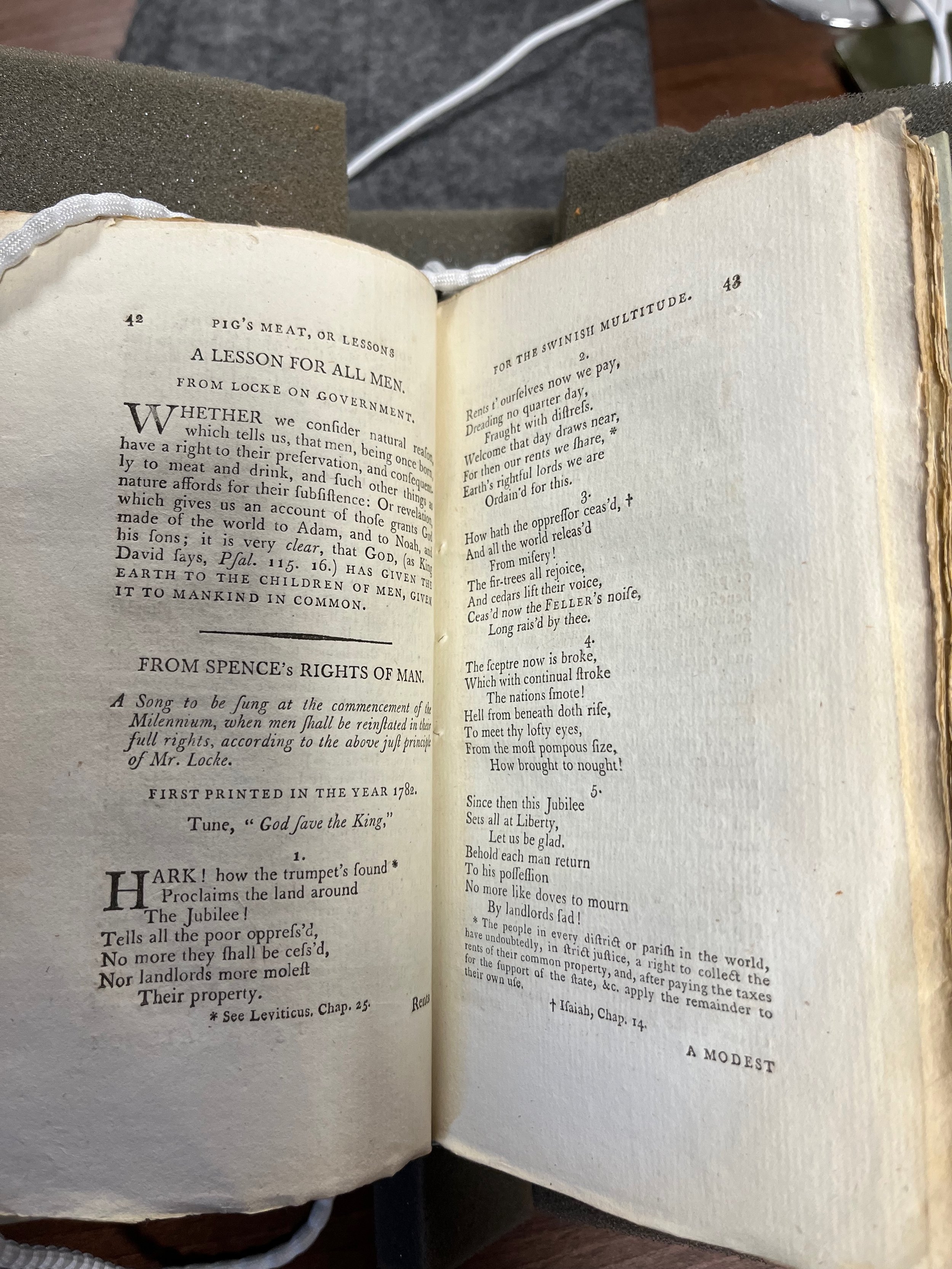

Spence’s ‘Rights of Man’ song from Pig’s Meat. Volume 1 (London, 1793). Robinson Library, Newcastle University. Rare Books RB 331.04 PIG. Reproduced with kind permission.

Very occasionally, Spence includes his own writings among the Pig's Meat extracts. The first volume includes a couple of his songs, and a version of his Plan in question and answer form. Here too, the juxtaposition of the extracts serves a deliberate purpose. Spence's first song appears immediately after an extract from John Locke's Two Treatises of Government; his second, between an extract from James Harrington and a speech by Oliver Cromwell; and the question and answer piece is sandwiched between two biblical quotations. By this means, Spence implies that his works are on a par with the texts surrounding them, thereby giving his works greater power and authority than if he had simply presented them in a pamphlet bearing his own name.

I discussed these ideas at a recent workshop on 'The Role of the Editor' at Newcastle University. Just as Spence's words gained greater power by being set alongside those of others, so my thoughts on this topic were enriched by listening to the other speakers.

The titles of the papers in the programme immediately raise questions about what we mean by 'editing'. The speakers discussed various examples including: authors editing of their own texts (Emily Price on William Lithgow, Joe Hone's paper which drew on evidence from proof copies); those editing texts written by others (Katie East on early modern editions of Cicero's works, Filippo Marchetti on John Toland's editions of the works of Giordano Bruni); the curation of a range of other 'texts' in periodicals and miscellanies (Kyra Helberg on the Lancet, Tim Somers on jestbooks); and even the editing of an archive (Harriet Gray on the Hedley Reports of the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society). By the end of the workshop we were wondering whether it would be better to think of editing as a task that various people undertake rather than a job title assigned to specific individuals.

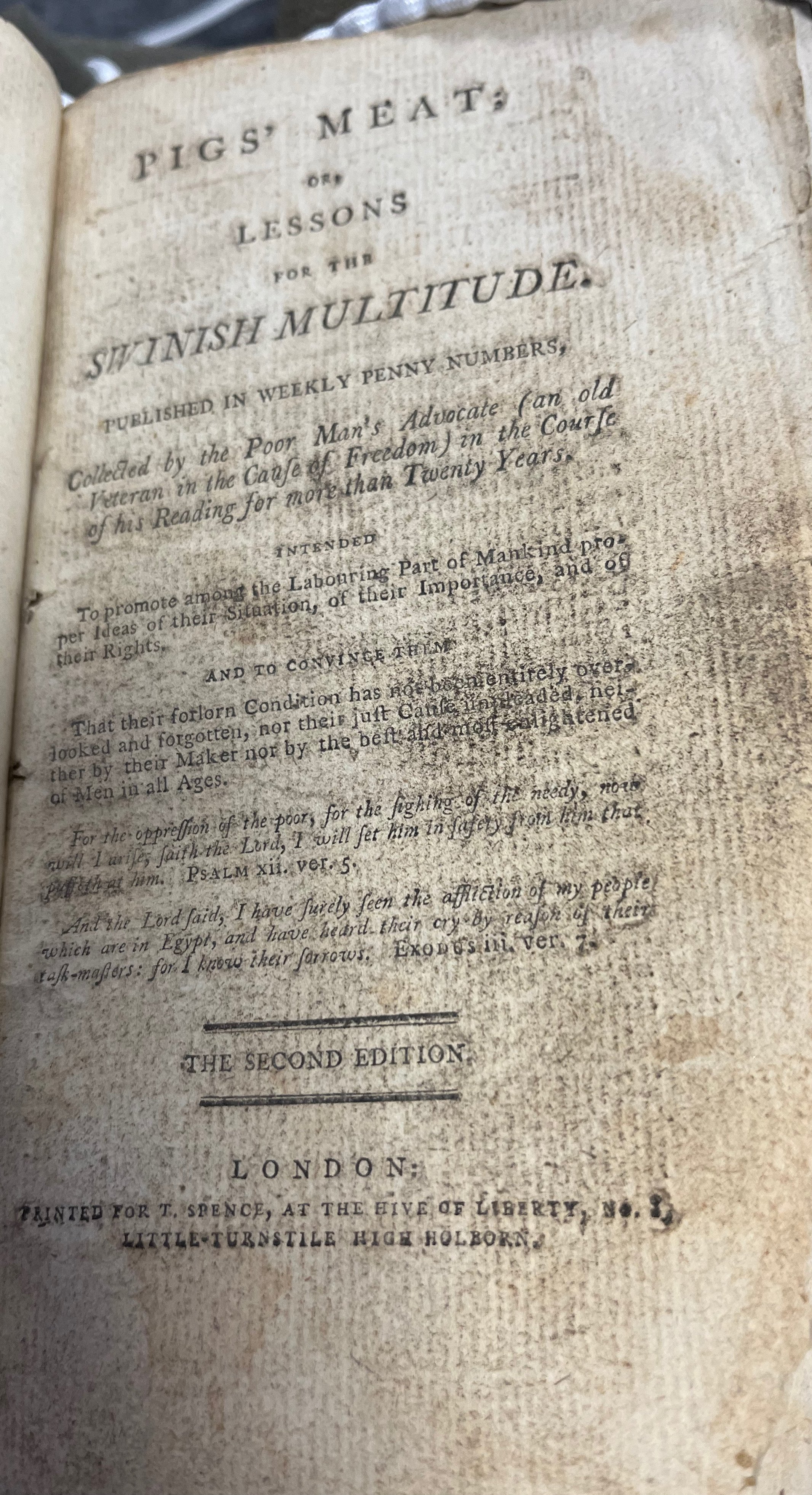

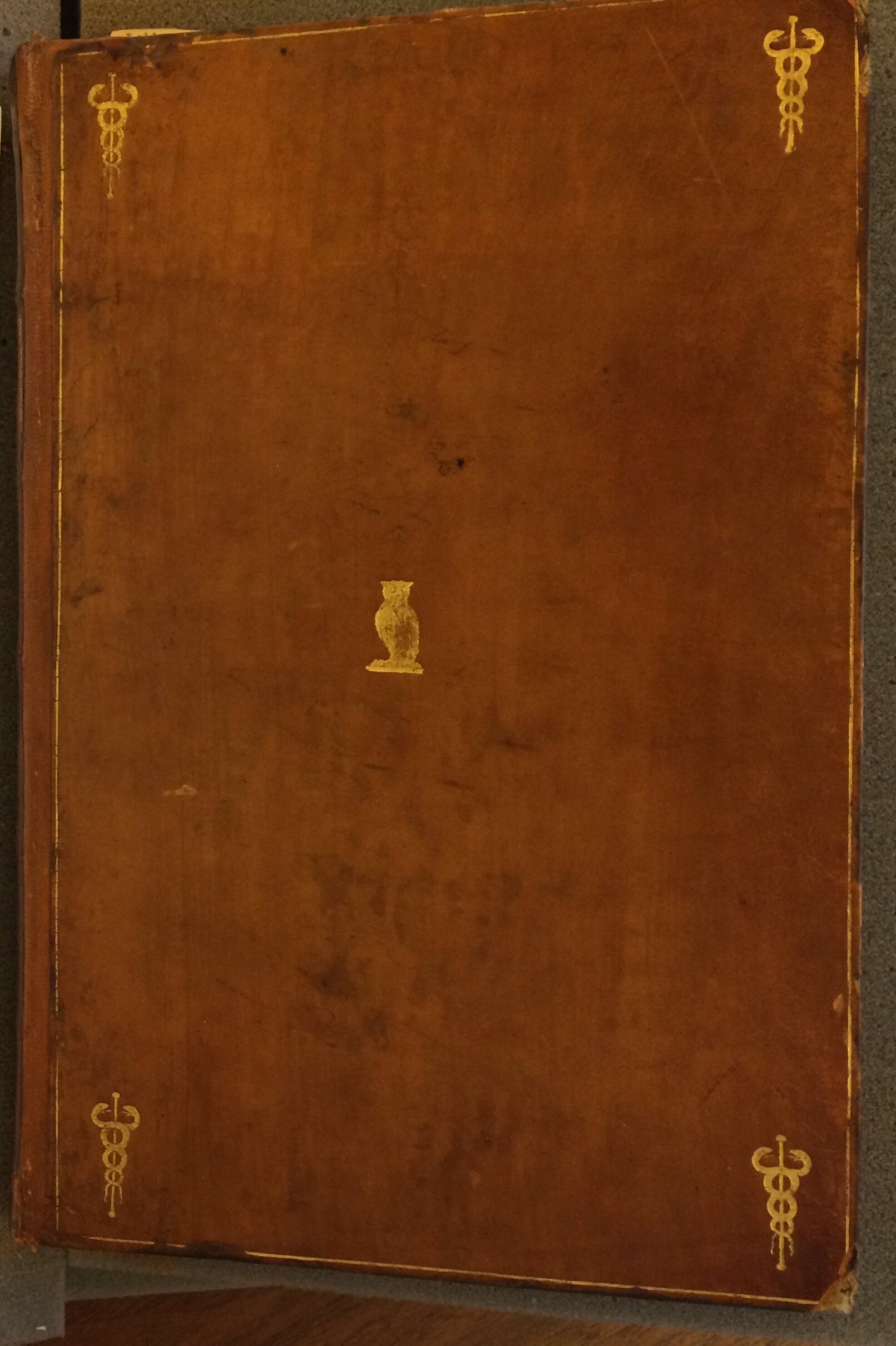

Title page of the Hedley Papers. From the Collection of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne. Reproduced with kind permission.

Just as the notion of an 'editor' proved more slippery than we had appreciated, so too the 'audience' to which editors addressed their works was far from static. Anthony Hedley may originally have produced the reports on the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society for himself (they appear to have only been presented to the Society by his daughter after his death) or at most as working documents for a small number of Society members. As Harriet Gray noted, this might explain why he was able to include details of controversies relating to the Society which were kept out of more public accounts. In his paper, Filippo Marchetti observed that Toland had more than one audience in mind when seeking to spread knowledge of Bruno's works, and that he deliberately produced different versions of the text for different audiences - adjusting the wording and accompanying evidence accordingly. Where Toland produced different texts for different audiences, Thomas Wakely (the subject of Kyra Helberg's paper) sought to address several different audiences through a single publication. The Lancet was intended for the medical profession (including both surgeons and students) but there is also evidence that it was directed towards - and read by - the wider public. As Emily Price's paper demonstrated, editors were not always in control of their audiences. She showed how Lithgow's travel narrative was originally directed towards members of the Court as a vehicle for advancing Lithgow's career and furthering anti-Catholic arguments, but that after his death it became a forerunner of the Baedeker or Rough Guide for travellers to the Continent.

There was also much discussion of particular editorial techniques, with a plethora of these on display in the papers. Katie East suggested that the context in which particular texts appeared could significantly affect how they were read - and even whether a particular text was considered 'political' or not. Cicero's speeches on Catiline were presented to early modern audiences in a range of formats: including in editions of Cicero's speeches; in collections of ancient speeches by various orators; in compilations of Cicero's works; in collections presenting historical evidence relating to the Catiline conspiracy; and even as interventions in contemporary political affairs, such as the South Sea Bubble. In each case the setting will have affected how the speeches were read. Both Harriet and I addressed the role that curation - and especially the juxtaposition of particular texts - can play in presenting a particular reading of an event or text. Emily and Tim both provided examples of adapting a text to fit new circumstances. And Kyra showed that Wakley was not above inventing correspondents to the Lancet to introduce particular topics or pursue his own ends.

The title page of the first edition of Gulliver’s Travels. Image courtesy of Joe Hone.

Finally, Joe Hone provided more insight into the question hovering over much of our discussion, namely how we can be sure of precisely who was responsible for editorial decisions in any given case. Emily had noted that Lithgow was away on his second voyage in 1614 when the first edition of his work appeared, and she wondered how his absence affected his editorial input. Joe demonstrated that the issue is complex. He showed us proof sheets in which an author insisted that particular words be rendered in italics - suggesting a high level of authorial intervention was possible. Yet he also explained how Jonathan Swift was furious when his printer removed the sharpest satirical barbs from the first edition of Gulliver's Travels, without informing him before publication. Of course, in most cases we simply do not have the evidence to be sure where responsibility lay. Yet, as the workshop made abundantly clear, there is much to be gained from thinking more deeply about editorial activity, and how this has shaped the documents that scholars use as evidence.