In his influential and prescient early assessment of the French Revolution, Reflections on the Revolution in France, Edmund Burke revealed his contempt for ordinary people - describing them as a 'swinish multitude' and, in the eyes of some, questioning their right to education. If the natural social hierarchy was challenged, Burke argued - 'learning', together with its natural protectors and guardians the nobility and the clergy would be 'cast into the mire and trodden down under the hoofs of a swinish multitude' (Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France. 8th edition. London, 1791, p. 117). The phrase hit a chord. As this Google Ngram illustrates, there was a huge spike in its usage following the publication of Burke's text, and it continued to be deployed well into the nineteenth century. The popularity and persistence of the phrase prompts several questions. Where did Burke get the idea from? What was the response to it? And why did it continue to be used for so long?

The origins of the phrase can be traced back to the Bible. In the Sermon on the Mount as recorded in Matthew Chapter 7 Verse 6, Jesus declared:

Give not that which is holy unto the dogs, neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet and turn again and rend you (King James Bible).

‘A Swinish Multitude’, by John (‘HB’) Doyle, printed by Alfred Duôte, published by Thomas McLean. Lithograph. 7 October 1835. National Portrait Gallery: NPG D41349. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

The reference not just to pigs, but also to trampling good things under foot, makes clear that this was the source of Burke's phrase (interestingly the conceit also appears in William Langland's poem 'Piers Plowman' and in John Milton's 'Sonnet XII', where the 'hogs' are condemned for failing to properly understand the nature of liberty). Moreover, the notion of 'pearls of wisdom' enhances the connection with learning. Burke's opponents in the 1790s were quick to subvert his jibe and turn it to their advantage.

Early responses simply expressed hostility to Burke's sentiment. As, for example, William Belsham's reference in one of his Essays, philosophical, historical and literary of 1791 and Charlotte Smith's in her novel Desmond. Commenting on the calmness of the French people on the King's return to Paris Lionel Desmond asserts, in a vein that perhaps also alludes and responds to Milton's use of the term:

This will surely convince the world, that the bloody democracy of Mr Burke, is not a combination of the swinish multitude, for the purposes of anarchy, but the association of reasonable beings, who determine to be, and deserve to be, free. (Charlotte Smith, Desmond. A novel, in three volumes. London, 1792, Volume 3, p. 89).

Around the same time there appeared a song entitled 'Burke's Address to the "swinish" Multitude', to be sung to the tune 'Derry, down down', which satirised Burke's position.

More substantial responses to Burke's argument about learning also began to appear. One of the earliest of these was A reply to Mr Burke's invective by the radical Thomas Cooper. Cooper was defending himself and his associate James Watt against an attack made by Burke in Parliament on 30 April 1792 concerning their presentation to the Jacobins on behalf of the Constitutional Society of Manchester. In the course of his defence, Cooper reflected on the relationship between knowledge and freedom. He condemned Burke for presenting national ignorance as a means of maintaining the position of the privileged orders and called instead for the dissemination of political knowledge so that the people could understand and secure their rights and freedoms:

Thus we find that public Ignorance is the Cement of the far famed Alliance between Church and State; and that Imposture, political and religious, cannot maintain its ground, if Knowledge and Discussion once finds its way among the Swinish Multitude. (Thomas Cooper, A Reply to Mr Burke's Invective. Manchester, 1792, p. 36).

Portrait of Thomas Cooper by Asher Brown Durand, after Charles Cromwell Ingham. Line engraving, 1829. National Portait Gallery: NPG D10570. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

This whole section of Cooper's work was inserted, unacknowledged, into the Address published by the Birmingham Constitutional Society soon after its establishment in November 1792. This is perhaps not surprising since the raison d'etre of these societies was precisely to spread political knowledge, and it was partly the actions of the London Society for Constitutional Information (alongside those of the Revolution Society) that had provoked Burke in the first place.

Around the same time, works began to appear that were presented as being written by 'one of the "Swinish Multitude"'. One of these was entitled A Rod for the Burkites. It was printed in Manchester and perhaps again emerged from the circles around the Constitutional Society. Sonnet for the Fast-Day. To Sancho's Favourite Tune by one of the swinish multitude was another satirical song to the tune 'Derry, down, down'. James Parkinson, writing under the pseudonym Old Hubert, published An Address, to the Hon. Edmund Burke, from the Swinish Multitude in 1793. Parkinson, a successful palaeontologist and surgeon who gave his name to Parkinson's Disease, was also an active radical with a sharp concern for the poor. Parkinson's Address argued that since men are all alike, they must all be swinelike. The difference, then, was between 'Hogs of Quality' who enjoy the luxuries of the stye and the poor swinish multitude who have to work hard to survive and are obstructed at every turn:

Whilst ye are chewing the greatest dainties, and gorging yourselves at troughs filled with the daintiest wash; we, with our numerous train of porkers, are employed, from the rising to the setting sun, to obtain the means of subsistence, by turning up a stray root or two, or perhaps, picking up a few acorns. But, alas! of these we dare not partake, untill, by the laws made by ye Swine of quality, we have first deposited by far the greatest part in the store house of the stye, as rent for the light of heaven and for the air we breathe. (James Parkinson, An Address, to the Hon. Edmund Burke, from the Swinish Multitude. London, 1793, pp. 17-18).

Moreover, Parkinson also argued that keeping the poor ignorant was a deliberate means of keeping them down:

it would be no more than justice, if these lordly Swine would enable us to instruct our young, so that they might be capable of comprehending the innumerable laws which are laid down for their conduct; and which should, they, even through ignorance, transgress, they are sure immediately to be sent to the county pound, or perhaps delivered over to the butcher. (Parkinson, Address, p. 19).

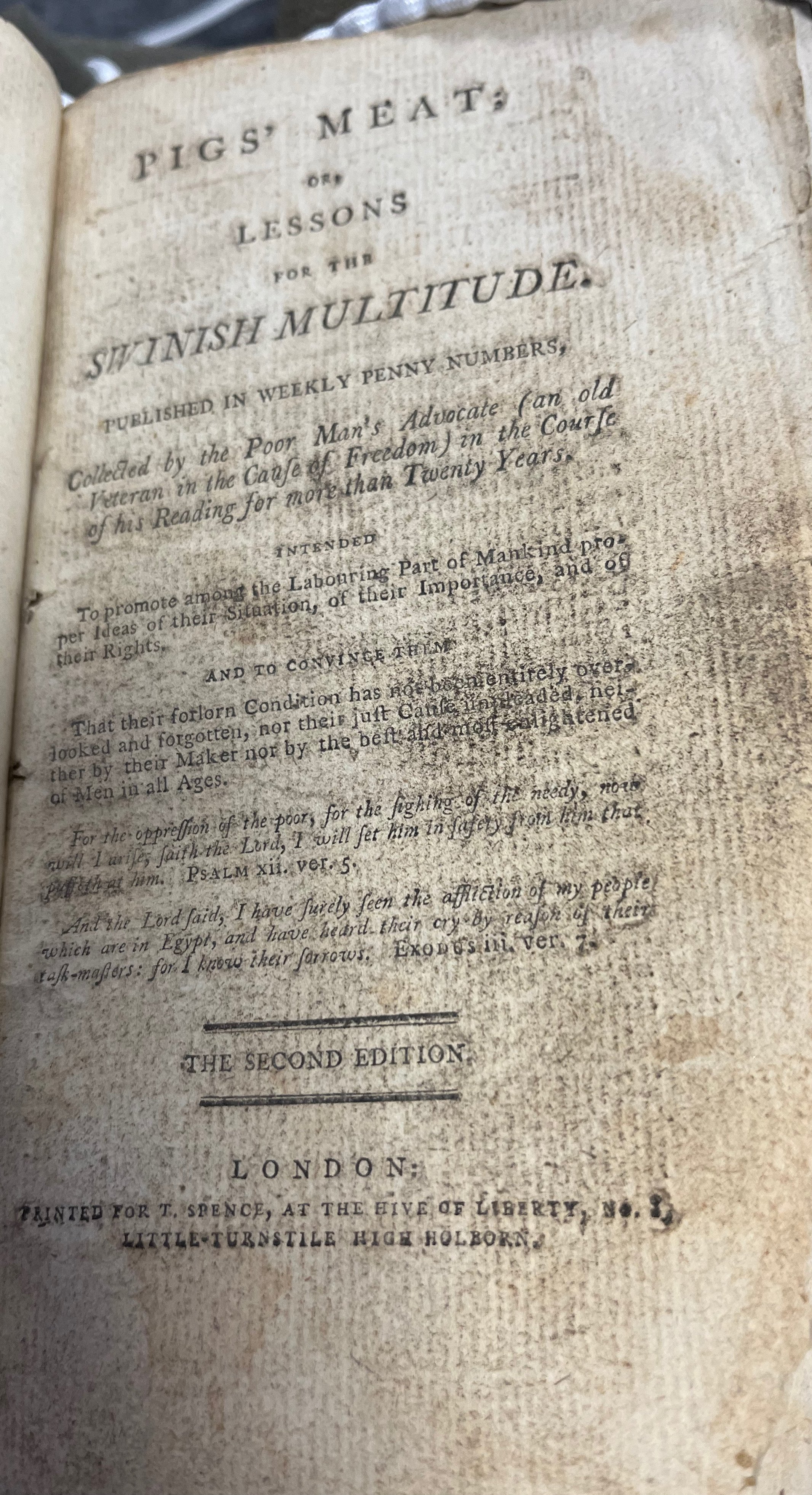

Title page of Spence’s Pigs’ Meat. Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle University. Special Collections: Rare Books (RB 331.04 PIG). Reproduced with kind permission.

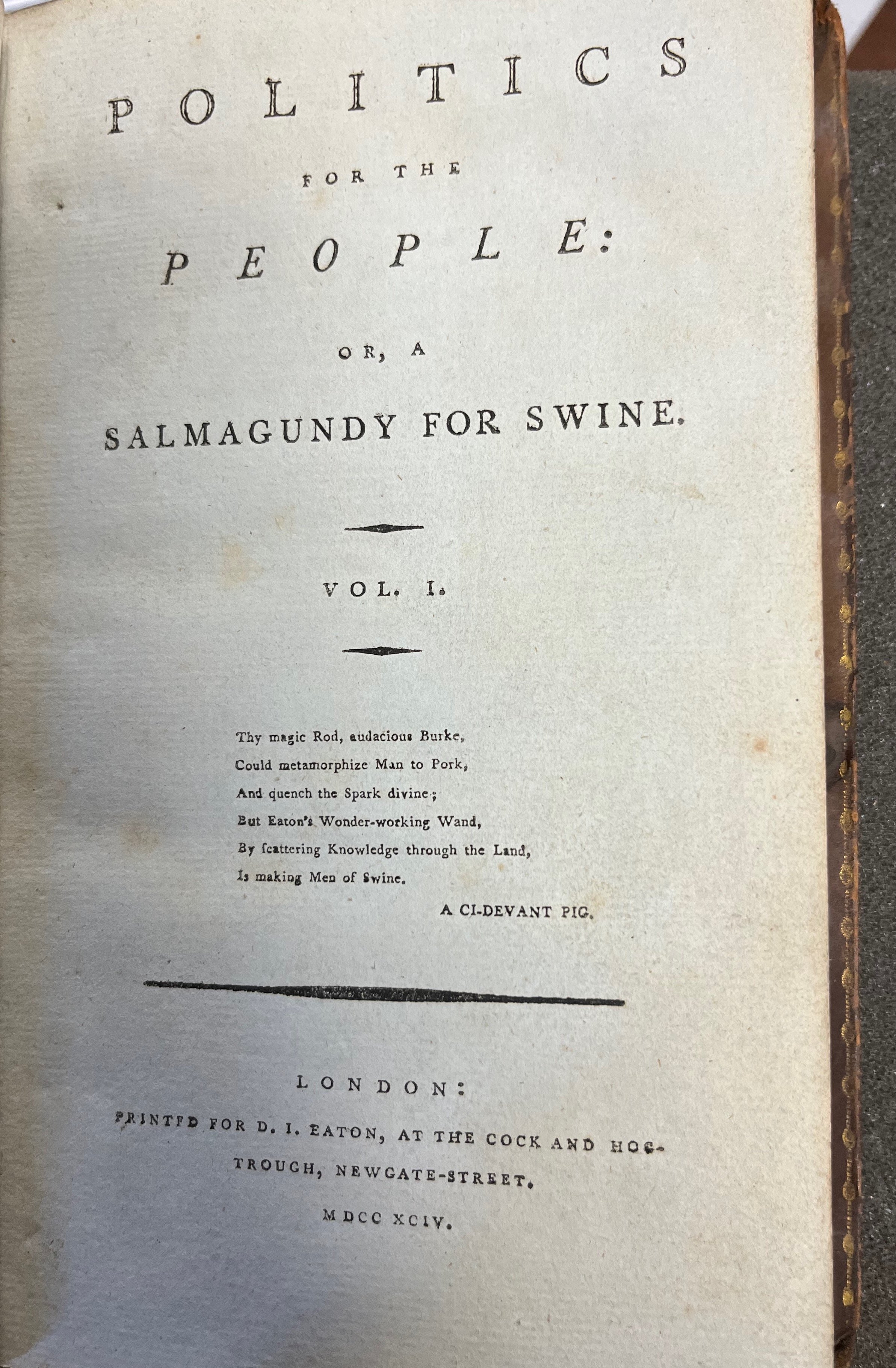

A further move by the radicals built on this point. In September 1793 two new periodical publications appeared that again commandeered the porcine language on the part of the poor. Thomas Spence's One Pennyworth of Pigs' Meat; or, Lessons for the Swinish Multitude was swiftly followed by Daniel Isaac Eaton's Hog's Wash; or, a Salmagundy for Swine (subsequently retitled Politics for the People). These works not only spoke to and on behalf of the so-called 'swinish multitude', as Parkinson had done, but were designed to provide them with useful political knowledge. They offered short extracts from a range of texts that were 'Intended' as Spence explained:

To promote among the Labouring Part of Mankind proper Ideas of their Situation, of their Importance and of their Rights, and to convince them That their forlorn Condition has not been entirely overlooked and forgotten nor their just Cause unpleaded, neither by their Maker nor by the best and most enlightened of Men in all Ages. (Thomas Spence, Pigs' Meat, title page).

Similarly, the full title of Eaton's publication explained that it consisted:

Of the choicest Viands, contributed by the Cooks of the present day, AND of the highest flavoured delicacies, composed by the Caterers of former Ages. (Daniel Isaac Eaton, Hog's Wash, 1793).

Title page of Eaton’s Politics for the People. Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle University. Special Collections: Friends (Friends 336-337). Reproduced with kind permission.

The extracts presented for the enrichment of the swinish multitude were eclectic. They included passages from: popular radical authors of the day such as William Frend, Joel Barlow, and John Thelwall; previous generations of radicals including John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, James Harrington and Algernon Sidney; but also more mainstream authors like Jonathan Swift, John Locke and Samuel Pufendorf. Moreover, the Bible was also a fundamental source for both editors, with quotes from various books of the Old and New Testaments being deployed to demonstrate that God favoured support for, rather than oppression of, the poor.

Though politically they were polar opposites Spence and Eaton endorsed what they saw as Burke's sense of the connection between ignorance and oppression and, therefore, between knowledge and resistance. Their hope was Burke's fear; that by providing the poor with political nourishment - feeding their minds as well as their bodies - they would be led to see and acknowledge both the oppression under which they suffered and the justice of their right to overthrow it. This, it was hoped, would provoke them into action. It did not, of course, but both the hope and the fear remain to this day.