Wolfenbüttel’s main square. Image by Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

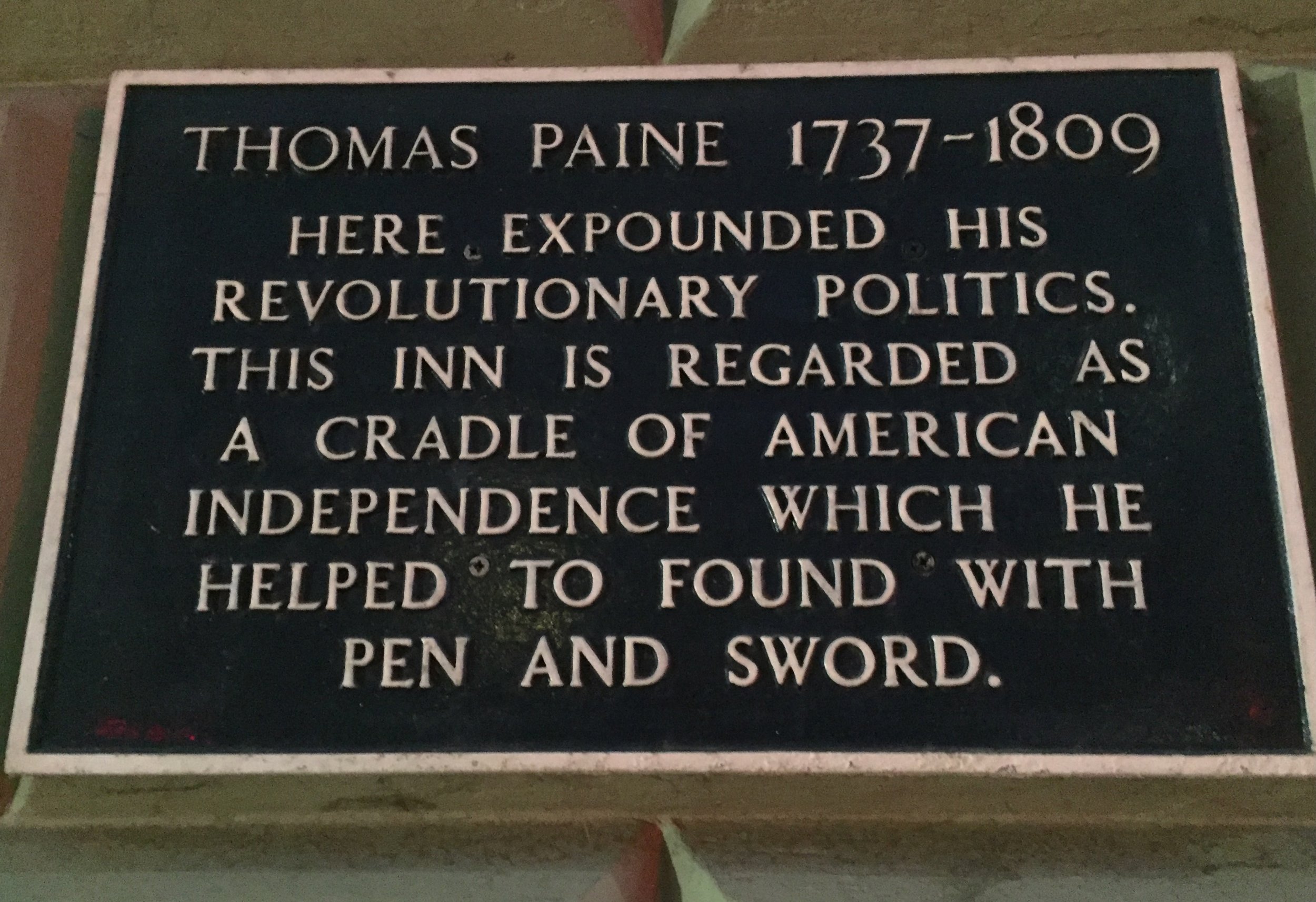

At the beginning of September I had the opportunity to return to the beautiful German town of Wolfenbüttel in Lower Saxony for another meeting of the Translating Cultures research group with which I have been associated for almost ten years. The group draws together scholars from across Europe who work on cultural translation in the early modern period. Last year we published a volume comprising chapters developed at our previous workshops. On this occasion we welcomed several new members as we turned our attention to how translations and translators are impacted by migration and mobility. As always with this group, the papers were, without exception, excellent and prompted much thought and discussion. In this blogpost I offer my personal reflections on three key themes that emerged from our discussions.

The title of Myriam-Isabelle Ducrocq's paper referenced James Harrington's suggestion that a politician must first be either an historian or a traveller. In a similar vein, several papers suggested that translation could offer an alternative to travel for those unable to do so. This was particularly true for women in holy orders including British Catholics who became nuns in convents on the Continent during the sixteenth century. Luc Borot discussed translations by these women using material from the Early Modern English Nuns in Exile database, produced by Caroline Bowden and others. Luc highlighted that while early modern men who took holy orders were often still able to travel - not least as missionaries - this was not typical for women. These women would travel to a continental convent but would then remain cloistered there unable to travel further or to return home. Translating spiritual and devotional texts was not only important for their own faith, but was also a means of maintaining connection with the outside world - and with their homeland. Veronika Čapská made a similar point about translation offering compensation for immobility, even suggesting that nuns used translation as their own version of missionary travel.

It was not only nuns for whom books acted as surrogates for travel. Veronika argued that the translations produced by the Sporck sisters - Maria Elenora and Anna Catharina - were used by their father (who often selected the books to be translated and checked the finished product) to make connections. He sent them as gifts to places where he (and certainly his daughters) could not go themselves.

High De Groot (Hugo Grotius) by Willem Jacobsz Delff, after Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt. National Portrait Gallery. NPG D26250. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

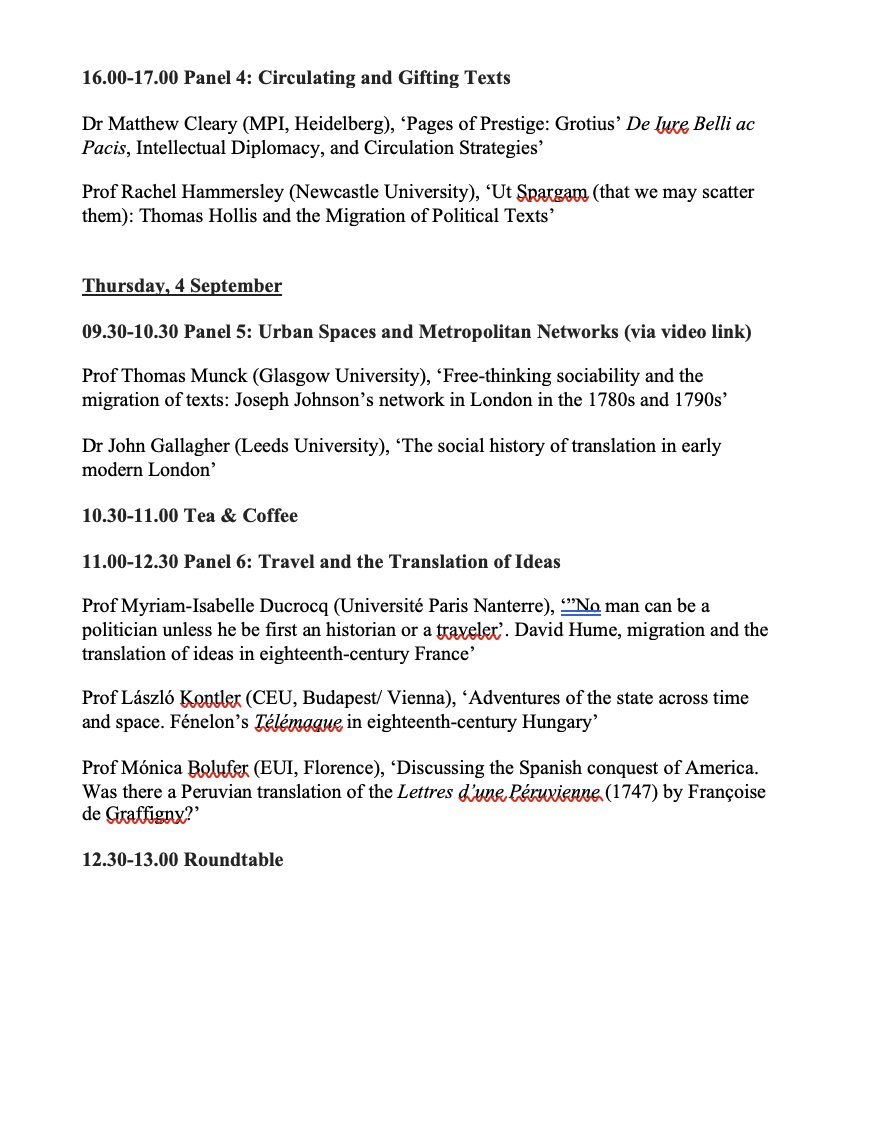

Something similar is true of the copies of De Iure Belli ac Pacis, that were distributed by their author Hugo Grotius, as discussed by Matthew Cleary, and of the books that Thomas Hollis sent abroad which were the focus of my paper. After returning from his grand tour in 1755, Hollis spent most of his time in London until retiring to his Dorset estate in 1770, yet through his gifts of books and the letters that accompanied them he built relationships with colonists in North America and with individuals and institutions in Europe; though the building of these relationships was limited by the fact that he insisted on making many of his donations anonymously. Grotius was restricted in where he could travel having been first imprisoned in 1619 and then (after escaping in 1621) exiled from the Dutch Republic. While Grotius's own freedom of movement was therefore limited, his books could go where he could not. Drawing on research conducted as part of the Census Bibliography project, Matthew demonstrated that Grotius used presentation and gift copies of his work to reward the loyalty of his supporters and to attract potential patrons, but also to engage opponents and rivals. Matthew used the phrase 'portable ambassadors' to describe the role that books played for Grotius. The idea of books acting as a surrogate for him when his own freedom of movement was restricted is only enhanced by the knowledge that his escape from the Dutch Republic in 1621 involved him hiding in a book chest.

In the same way, László Kontler's paper on eighteenth-century Hungarian translations of Fénelon's Télémaque showed how this book allowed his ideas to exercise an influence in very particular political situations in Hungary, despite Fénelon himself never venturing there. The use of books to spread ideas to wider audiences than could be achieved by travelling was also reflected in both Alessia Castagnino's paper on translations by Jesuits and Ariel Hessayon's on translations of works of early modern alchemy. Ariel noted the paradox that while alchemical texts were deliberately obscure to ensure that they could only be fully understood by the 'right' people who had the required knowledge, their authors nonetheless wanted them to be disseminated widely - so that they could reach the appropriate audiences wherever they were. Translations were crucial in facilitating this. Alessia argued that the Jesuits deliberately used books - and especially translations - to advance their cause among people whom they would not meet personally. She used the case study of the 1794 translation by Domingos Teixeira of William Robertson's An Historical Disquisition Concerning the Knowledge which the Ancients had of India to illustrate this. This work was chosen less for the information it offered and more because Robertson was a popular author whose work would be widely read. At the same time, Teixeira 'corrected' Robertson's depiction of the Portuguese Empire and Jesuit history, and adapted the work to advance the Jesuit cause. This involved rewriting and adding to the text, but also providing a new table of contents to draw the attention of the reader to particular parts of the work.

Here then we move to a second theme that repeatedly appeared - the idea of translator as author. This point was initially raised by Luc who noted that in French law the translator of a work is legally defined as its author. As is evident from Alessia's case study, this could be true in a direct sense. The 1794 translation of Robertson's work is almost twice as long as the original and Teixeira's corrections and additions change the focus and purpose of the text so that the authorial intention behind the translation is different from that of the original.

The title page of Pierre Coste’s 1792 translation of Locke’s Essay. From Wikimedia Commons.

Other contributors to the workshop told similar stories. The Huguenot Pierre Coste, who was the focus of Ann Thomson's paper, aspired to be an author but was so good at translations that he rarely had time for his own works. Nonetheless, Ann showed how when translating John Locke's correspondence with Bishop Stillingfleet, Coste operated in crucial ways as an author rather than a translator. He produced two versions of this exchange. The first in Nouvelles de la République des lettres in late 1699 and the second in the translation of Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding that appeared in 1729. Though the two versions differed in important ways - the former being more fideistic in tone, the latter more deistic - neither properly reflected what Locke actually wrote but were rather Coste's own work. As Ann explained, this is significant because the latter was crucial in setting the tone for the reception of Locke's ideas in eighteenth-century France.

Edmund Ludlow by an unknown artist. National Portrait Gallery. NPG D19486. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

In the same session, Gaby Mahlberg discussed the translations of The Speeches and Prayers of the Regicides and of Edmund Ludlow's Memoirs that appeared in Europe in the late seventeenth century. Both works were subject to significant re-structuring by their translators to reflect the views of their respective audiences. Gaby showed how the French translation of The Speeches and Prayers: Les Juges Jugées, which was facilitated by Ludlow himself, presented a different title and structure so as to make it more accessible to an audience less familiar with the events. The Yverdon-based printer who produced the work also added accounts of the persecution and trials of others, including Henry Vane, John Lambert, John Barkstead, Miles Corbett and John Okey. The last three were captured in the United Provinces and Ludlow was angry with the Dutch for collaborating with George Downing in handing them over. This incident then impacted the Dutch translation of Ludlow's Memoirs, the third volume of which was very critical of the Dutch. Though the translation was generally faithful to the original, it did not include the controversial third volume.

The case of the Spanish translation of the epistolary novel Lettres d'une Péruvienne, discussed by Mónica Bolufer, had many similarities with Alessia's Jesuit case. Here the 1792 Spanish translation by Maria Roméro Masegosa y Cancelada included a wealth of additional material, including a preface, lengthy footnotes expressing the translator's views, and two additional letters which served to change its ending. The purpose of these alterations was to offer a more positive account of the Spanish conquest of South America, about which the original had been critical.

This was one of several cases of translation providing the opportunity for a woman to act as an 'author' - in this case commenting directly on a political topic. The issues surrounding female authorship were highlighted in Veronika's reference to the fact that the translations by the Sporck sisters are sometimes referred to on the title page and spine as being by their father. Similarly, in his paper on Therese Huber, Elias Buchetmann noted that Therese worked closely with her second husband Ludwig Ferdinand Huber, so that it can be difficult to separate their works. Moreover, she continued to attribute some of her works to him even after his death.

Finally, almost all of the speakers engaged in some way with the fact that translations inevitably involve - indeed require - a wider network of collaborators beyond the author and the translator. Several different types of networks were explored across the workshop.

Joseph Johnson by William Sharp, after Moses Haughton the Elder. National Portrait Gallery. NPG D3316.

The first, and most obvious, is of course intellectual networks. These alone can take different forms. They might be tangible and even formal as in the case of John Locke's links to Arabic scholars at Oxford. In her paper Luisa Simonutti noted that Edward Pococke senior, who was Chair of Arabic at Christ Church, taught Locke and that Locke in turn taught Edward Pococke's son. Thomas Munck's paper focused on another tangible intellectual network, that of the printer Joseph Johnson, which operated via the dinners that he regularly hosted and his extensive correspondence with authors and translators. In his paper Thomas set out three potential methods for establishing who was part of this network: by analysing Johnson's surviving letter book - which is a rich source - but which only covers a small period of his life; by examining the Analytical Review that Johnson edited between 1788 and 1798 to identify the works reviewed and (where possible) those who wrote the reviews; and by identifying all the books that Johnson printed himself - a huge but potentially rewarding task.

Of course, not all intellectual networks are synchronic. Luisa's paper, in focusing on the translations of a philosophical novel by Ibn Tufayl (born c.1100), also demonstrated Locke's connection to a wider cross-generational network comprising Tufayl himself and other writers inspired by his ideas including Baruch Spinoza, Robert Boyle, Daniel Defoe and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Similarly, the other paper in that session, by Ariel Hessayon, demonstrated the vast transnational intellectual network that developed as a result of the translations and correspondence of Johannes Fortitudo Harprecht. Moreover, translations and correspondence worked in tandem here, since fully understanding the alchemical texts that Harprecht translated often depended on interpersonal relationships. Elias's paper on the Hubers also highlighted the importance of intellectual networks. For example he showed the close connection between the Hubers and Isabelle de Charrière, whose works they translated, as well as noting the ways in which Therese Huber's individual intellectual network interacted with that of each of her husbands. Here, as elsewhere, there was overlap between intellectual and family networks.

Kinship was also important in the building of religious networks including those, discussed by Luc Borot, which made it possible for English Catholic women to establish themselves in convents on the Continent, and those that operated via the Stranger churches in London as discussed in John Gallagher's paper. For religious exiles arriving in London in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the churches were a crucial venue for the forging of connections and establishing oneself in a new country. John showed how these communities relied on translators who worked as notaries, and who used their linguistic skills both within the church and at the Royal Exchange. John's paper was particularly important to our discussion in that it highlighted the fact that not all early modern translation concerned key literary or political texts. Notaries translated various documents including those required to facilitate transnational trade and the wills of foreigners based in London. Despite being prolific translators their work remains largely unknown.

The edition of Algernon Sidney’s Discourses Concerning Government (London, 1751) that Thomas Hollis sent to the Library at Bern. Bern, UB Münstergasse, MUE Hollis 66. Reproduced with permission. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

The idea that there was a close connection between translation and trade was also noted in other papers in relation to literary and political translations. Miriam-Isabelle Ducrocq showed how the circulation of the philosophical and historical writings of David Hume depended not only on those conventional intellectual networks that we might expect but also on less obvious connections. In particular the wine merchant John Stewart of Allenbank (1723-1781) and his son were crucial to the dissemination of Hume's works in France. Most interestingly, they were responsible for putting Hume in touch with Montesquieu and in facilitating the exchange of books between the two. While this case was unusual, it is important to remember the production and dissemination of books often relied on trade and craft as well as intellectual networks. In my research on Hollis's dissemination project I have identified various individuals including booksellers, printers, engravers, bookbinders, and shipping merchants on whom Hollis relied. While his focus was the dissemination of books and ideas, the practical skills of these artisans and traders were crucial to the fulfilment of his aims.