I feel lucky that we have so many excellent early modern intellectual and cultural historians based at Newcastle with whom I can talk and collaborate. One of these is my friend and colleague Gaby Mahlberg who currently holds a Marie Sklodowska-Curie postdoctoral fellowship with us. In late June, Gaby organised a workshop as part of her fellowship which brought a number of excellent scholars who work on the translation of political texts to Newcastle. The workshop explored a number of themes, including: the purpose of translations; the roles of the individuals involved in producing them; the building of canons; and free speech.

As someone who has worked on translations since the very beginning of my research career, I have often reflected on their purposes. We tend to assume that the main aim of a translation is to disseminate the ideas contained within the text and that those involved in producing the translation identify the text as relevant to their own cultural and political context and audience. Yet, some of the examples discussed at the workshop suggested that this is not always the case.

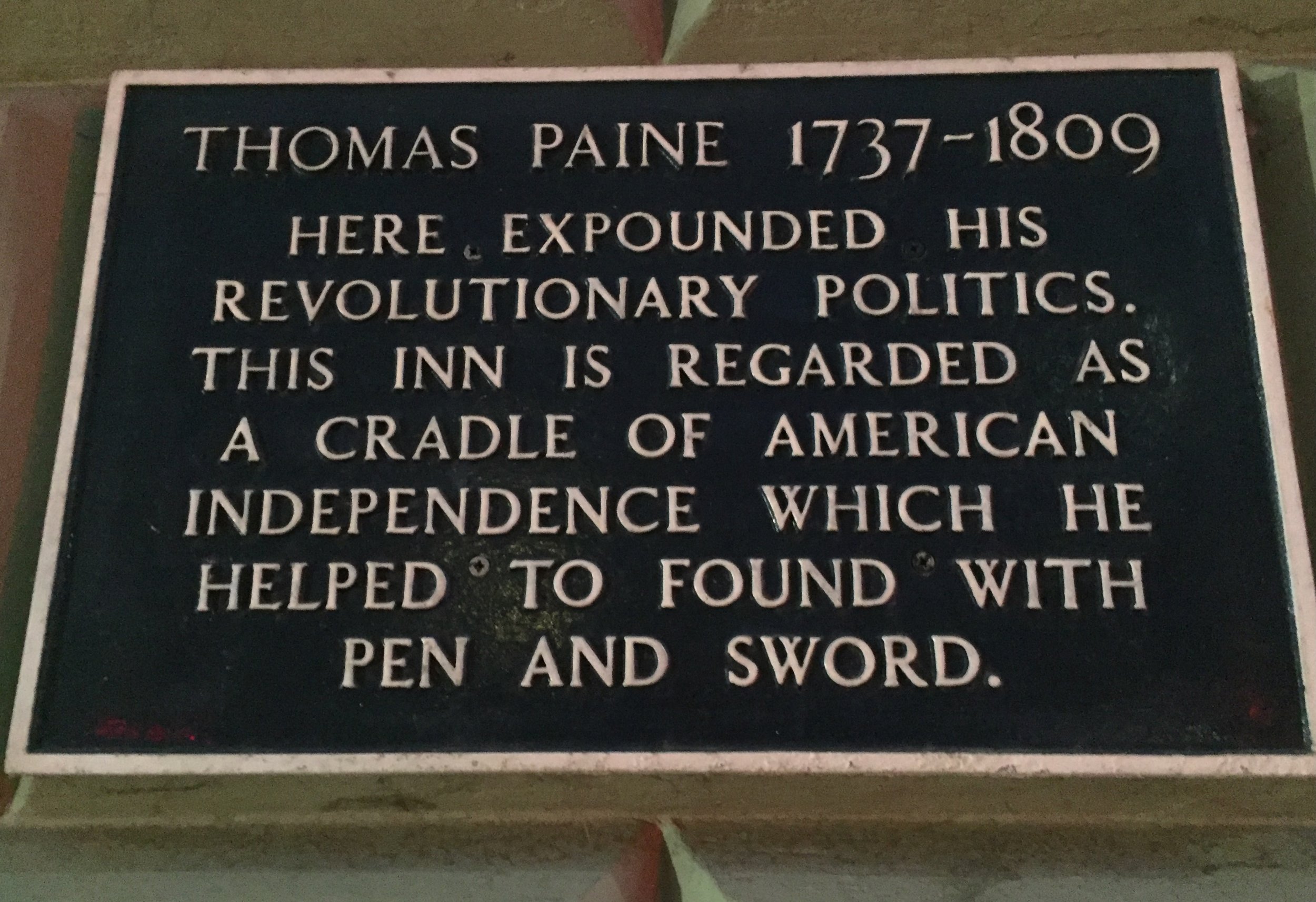

Plaque commemorating Thomas Paine’s time in Lewes, East Sussex, which appears on the wall of the White Hart Inn. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

Elias Buchetmann briefly discussed the partial translation of Thomas Paine's Rights of Man, which appeared in Leipzig in 1791. Though it made available part of Paine's famous work to a German audience, the aim appears to have been less to disseminate Paine's ideas than to contain them, reinforcing instead the position of Paine's antagonist Edmund Burke. This is evident in the way in which the footnotes are used to contradict and correct Paine's views, so that the reader does not receive Paine's ideas in isolation but via a Burkean lens.

Ariel Hessayon's paper on the translation of Gerrard Winstanley's New Law of Righteousness raised a different question: whether a translation is always produced for circulation. We know about this German translation of Winstanley's text from the catalogue of the library of Petrus Serrarius, though no copy of the translation survives. The translator was probably Serrarius himself. We might assume that since he could read English he must have translated it to circulate among others who could not, but in the discussion we noted that this is not necessarily the case. Katie East reminded us that translation was a long-established pedagogical technique for those learning classical languages and that this could equally apply to the learning of European languages. It was also noted that translating a work could be used to develop a deeper understanding of it.

A title page from Cato’s Letters. Taken from the Internet Archive.

Several papers challenged the assumption that a translated political text is necessarily seen as relevant to the political context into which it is translated. The transmission of English republican ideas into France, which has been explored in detail by several of the workshop participants, certainly seems to fit this model. The Huguenots, who were particularly concerned with justifications for resistance, translated works by Algernon Sidney and Edmund Ludlow. Whereas Harrington's works, as Myriam-Isabelle Ducrocq's paper reminded us, came into their own during the French constitutional debates of the 1790s. Several papers, however, made clear that the translation of English texts into German tells a rather different story. Both Felix Waldmann in his account of the German translations of John Locke's works and Gaby Mahlberg in her discussion of the German reception of Cato's Letters highlighted a sense among both translators and reviewers that those texts applied specifically to England, and that their insights and models could not easily be applied in a German context. Of course, this could be a rhetorical device to distance the translator, editor, or printer from potentially controversial ideas, but it is certainly true that the German states in the eighteenth century were very different from that of early modern England.

As well as thinking about the purpose of translations, several speakers touched on the role of the individuals involved in their production. Thomas Munck's paper drew attention to the fact that, despite being in France during the Revolution, Thomas Paine contributed very little to debates and events there. Though he was a member of the Convention, he hardly ever spoke, he did little while in France to promote his own works, and though he advocated certain proposals - such as a fairer tax system - he had little to say about the practical means of achieving them. In the discussion that followed we reflected on how we should classify Paine. Was he a political thinker, a politician, an activist, or more like a journalist or observer (at least during his time in France)? It was also noted that political thinkers and writers do not always make good politicians.

Similar questions were asked about Pierre Des Maizeaux who was the focus of Ann Thomson's paper. He was not an original thinker, nor was he much interested in political discussion - being more of an erudite scholar. Yet he was crucial to the dissemination of political ideas thanks to his role as an intermediary, editor and populariser.

These examples point towards a wider question of the connection between theory and practice. Today it often seems as though politicians engage very little with political thought, while academics engaged in political thinking have little influence on practical policy. Yet, it might be argued, both are necessary if improvements are to be made. Thinking about the channels that exist - or could be developed - between the two, and celebrating the intermediaries and popularisers who forge and sustain them, has potential value for us all.

Algernon Sidney by James Basire after Giovanni Battista Cipriani, 1763. National Portrait Gallery NPG D28941. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

The role or identity of key thinkers was approached from a different perspective in Tom Ashby's paper on the reception of Algernon Sidney's ideas in eighteenth-century Italy. Tom's account of the figures Sidney was associated with by different Italian thinkers at different times prompted much discussion. Initially he was linked, as one might expect, to natural law thinkers such as Samuel Pufendorf and Locke. But the Italian Jacobin Matteo Galdi associated Sidney, instead, with a more eclectic list of thinkers including Francis Bacon, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the baron de Montesquieu, Gaetano Filangieri and Giambattista Vico. Galdi presented these figures as advocates of what he called 'new politics' (presumably building on Vico's 'new science'). Similarly, Christopher Hamel reminded us that the marquis de Condorcet associated Sidney with René Descartes and Rousseau in his Esquisse, and Sidney was also regularly linked in the eighteenth century with his contemporary John Hampden as examples of patriotic martyrs. While some of these links appear bizarre, and while it can be difficult to understand the thinking behind them, they do offer another potential avenue by which we can explore the tricky question of reception.

Finally, some of the papers touched on issues of free speech and toleration. Christopher Hamel drew attention to the idea of 'disinterested historians' in his paper on the French reception of Thomas Gordon's Discourses on Tacitus. Reviewers praised Gordon's tactic of simply describing, for example, 'the flattery which reigns at the court of tyrants' without feeling the need explicitly to pass judgement. It was noted that the Royal Society had emphasised the idea of disinterested scientists who would develop conclusions purely on the basis of reason, observation, and experimentation. The suggestion was presumably that historians could do something similar.

Ann Thomson reflected in a similar way on the approach of Huguenots such as Des Maizeaux and Jean Le Clerc. Des Maizeaux has sometimes been seen as advocating irreligion on account of his willingness to circulate free thinking works, but Ann suggested that his aim was really the promotion of toleration. This was reflected in the fact that he invested a great deal of time and energy into producing an edition of the works of William Chillingworth, who was a latitudinarian Anglican. Similarly, in a review of John Rushworth's collection of documents from the civil wars, Des Maizeaux noted a republican bias in the selected texts and suggested that royalist texts should be published as a complement. Jean Le Clerc also seems to have been concerned with offering a balanced account of the mid-seventeenth-century conflict. When reviewing the Earl of Clarendon's History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England in Bibliothèque choisie he noted that it was 'very zealous' for the King's party and suggested that Edmund Ludlow's Memoirs be read to provide a contrast or comparison.

These examples reminded me of Thomas Hollis. As I have discussed previously in this blog, Hollis published not just works that he favoured but also those expressing opposing views - on the grounds that readers needed to read both and judge for themselves. Moreover, Hollis also picked up specifically on Clarendon's History, though his suggestion was that it should be read alongside the works not of Ludlow, but of John Milton.

In short, the workshop provided much stimulation for thought about the role and importance of translations and translators in adding to our understanding of early modern political cultures, and the relationship between ideas and practical action. At the same time, it prompted thought about that relationship today. What means can be used to bring the rich political thinking of academics to bear on contemporary political issues? And what specific role might 'disinterested historians' play in this task?