Courtesy of the pandemic, during October I 'attended' two conferences in two different countries (the United States and Germany) without leaving my study. While I have attended various virtual conferences over the last eighteen months, these were the first hybrid events to which I have been invited. There is, of course, much that is good about this shift - not least the fact that reducing our international travel is better for the environment and that events that include a virtual dimension are more accessible for those with caring responsibilities. The fact that we have all been forced to get to grips with online platforms such as Zoom during the pandemic means these events tended to work more effectively and run more smoothly than the occasional attempt at hybrid events I attended in the past. Nevertheless there are, of course, trade-offs. In one sense it is good that I could attend these events while still fulfilling my duties as a teacher, Director of Research for my School, and a mother. But whereas when one attends a conference in person other duties recede into the background for a couple of days, this time I had to intersperse listening to conference papers with other activities, including transporting my daughter to football training and holding office hours with students, making it difficult to immerse myself fully in the topic of the conference. As Adam Smith would have recognised, there is a cost involved in switching from one activity to another.

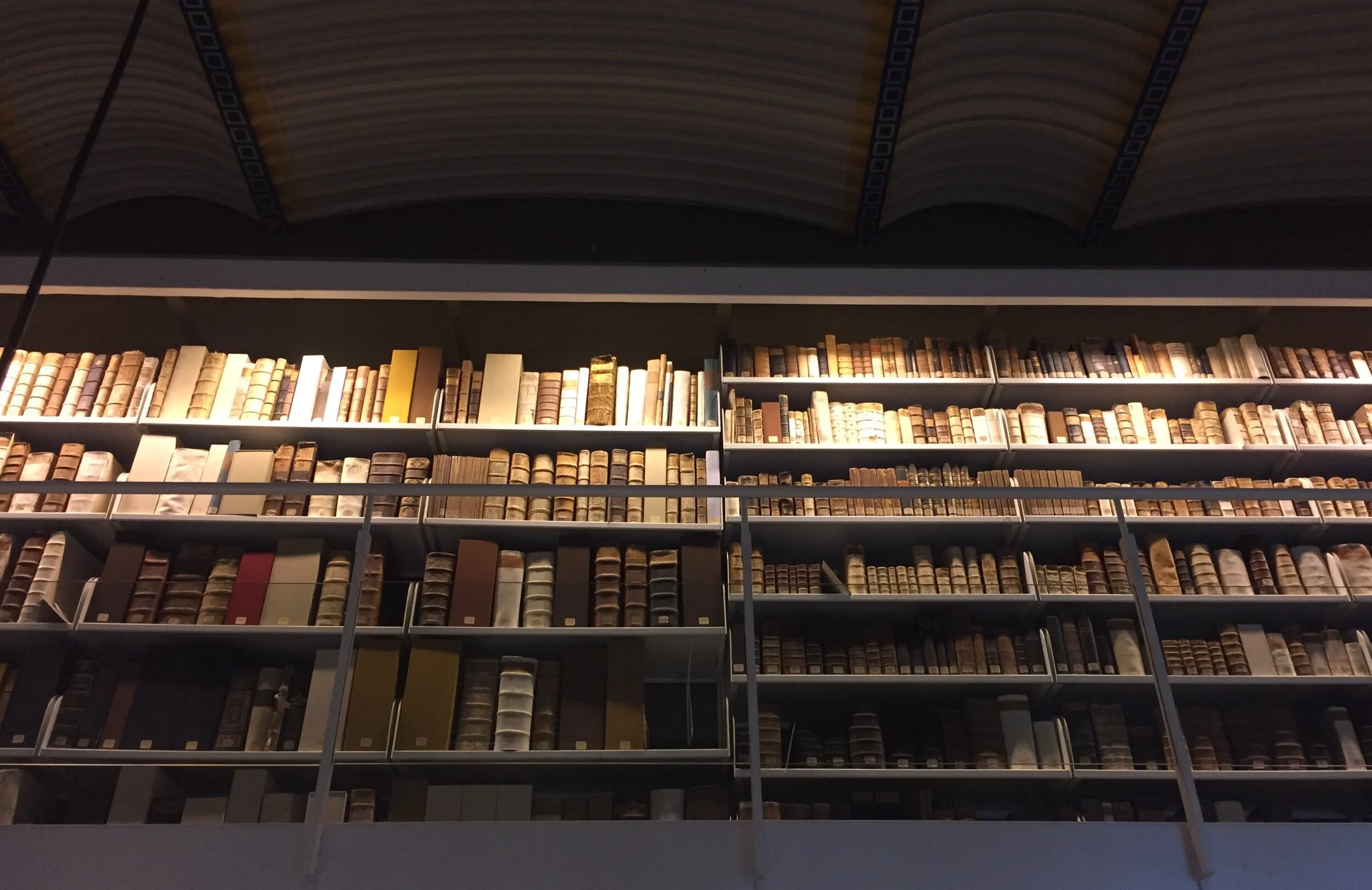

Nonetheless both conferences provided much food for thought. In this blogpost, I will comment on just one of them: the latest in a series of workshops led by Thomas Munck and Gaby Mahlberg, and held at the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel Germany, involving a group of European scholars interested in cultural translation. Since this was the fourth time we have met as a group it was very much a case of pulling together strands of thought that we have been working on for a while, with a view to producing a joint publication. All the same, the papers generated some new ideas for me.

Ironically, given how long we have been thinking about cultural translation, one observation I had was about the limits of what we can know. This was brought directly to our attention by Thomas Munck in his paper: 'Untranslatable, unsellable, unreadable? Obstacles, delays and failures in cultural translation in print in early modern Europe'. Thomas's starting point was why some authors and works are not translated despite exploring potentially interesting and relevant topics. As an example he highlighted the case of the Scandinavian thinker Anders Chydenius, who wrote on popular eighteenth-century topics such as population decline, free trade, and freedom of the press, but whose works were not translated from Swedish into other European languages. Thomas identified various reasons why works do not get translated: what is written could be difficult to convey in another language; there might be conceptual barriers to translation - in that the ideas expressed may be considered out of bounds in other contexts; the works might be deemed boring and therefore unsellable; or there could be fears that they would be censored either pre- or post-publication. In addition, other members of the group noted that the existence of Latin editions can be seen to render a translation unnecessary. The difficulty for us as historians of the early modern period is in determining what the reason or reasons were in any particular case. Other papers brought up specific examples of this. Gaby Mahlberg noted that there is evidence that both a French and a Latin translation of John Toland's Anglia Libera were planned, but there are no extant copies - meaning either that the translations did not materialise or that no copies survive. We do not know which is the case, even less why. In his paper on the French translations of Thomas Hobbes's works, Luc Borot raised several related questions: why some works by Hobbes were translated but not others; why parts of some works were translated but not the whole work; and why some translations flourished while others floundered. Even, as in the case of Hobbes, where extensive correspondence between author and translator exists, we can often do little more than speculate on the whys and wherefores.

Paul Rycaut, after Sir Peter Lely c.1679-80. National Portrait Gallery NPG 1874. Reproduced under a creative commons licence.

While there is a lot that we do not know, there is also a great deal that translations can reveal, not least about the preoccupations of the translator, printer or their audience. Ann Thomson's fascinating paper on translations of works about the Ottoman Empire highlighted several examples of translations being used for purposes that were different from - and sometimes even at odds with - the intentions of the original work and its author. One such example is the seventeenth-century French translation of Paul Rycaut's work The Present State of the Ottoman Empire. His account was designed to highlight the benevolent nature of the rule of the Stuarts in England - and at the same time to condemn the rule of the Puritans during the 1650s as being more like oriental despotism. The references to the Stuarts were, however, cut from the French translations and instead the 1677 version used Rycaut's book as a vehicle for discussing the situation of Protestants in France. Similarly, Luisa Simonutti's paper shed light on the manuscript translation of the Doctrina Mahumet which is held among John Locke's papers in Oxford and clearly contributed to discussions about toleration among his circle.

‘Carte de Tendre’ from Madeleine de Scudéry’s novel Clélie. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons.

Another adaptation between source text and translation was explored in Amelia Mills's excellent paper on Aphra Behn's translation of Paul Tallemant's Le Voyage de l'Isle d'Amour. Tallemant's work drew inspiration from Madeleine de Scudéry's 'Carte de Tendre', which appeared in her book Clélie, a Roman History; and Amelia showed us a beautiful copy of the original 'Carte de Tendre' (which survives in the Herzog August Bibliothek). The map was designed to demonstrate how suitors could find their way into the affections of women by travelling to one of three destinations: Tendre sur reconnaissance, Tendre sur inclination or Tendre sur estime. Tallemant reinvented Scudéry's map shifting the destination from tendre to amour - with its more erotic overtones embodying a male rather than a female perspective. In her translation of Tallemant's text, Aphra Behn moved the focus back to a female-centred vision and to the intellectual meeting of minds that had been behind Scudéry's original. As Amelia demonstrated, this was reflected in the translation of particular words with, for example, the French word 'plaisir' not rendered as the obvious English equivalent 'pleasure' but rather the less emotionally charged 'content(ment)'. In doing so, Amelia argued, Behn was very deliberately looking back to the decade of Scudéry and her circle, and suggesting that there was much that English women of the 1680s might learn from them.

In Behn's case the shift of tone and emphasis came largely through the translation of particular terms, but in many other cases it came instead through paratextual material. Alessia Castagnino talked in her paper about the translations of the Abbé Noël Pluche's work Le Spectacle de la Nature. She noted that the Spanish translation incorporated footnotes which were deliberately used to emphasise the work of Spanish scientists and to highlight the important contribution of the Jesuits to the advancement of global knowledge.

Footnotes were also used to shift the focus of James Porter's Observations on the Religion, Law, Government and Manners, of the Turks, which was discussed in Ann Thomson's paper. She noted that the edition of the French translation produced by the Société Typographique de Neuchâtel added a wealth of footnotes which developed the themes of toleration and the condemnation of prejudice and superstition. Thus a translation of a work that was originally intended to offer a balanced - even sympathetic - account of the Ottoman Empire, was used by the STN as a means of attacking Catholic intolerance. Another example of a printer influencing the reading of a work through the addition of paratextual material was noted in the presentations given by Mark Somos and his team, who are working on the Grotius census. As Ed Jones Corredera reminded us, the important series of works on republics published by Elsevier in the seventeenth century included often quite elaborate frontispieces that were the work of the printer rather than the author or translator, allowing the printer to stamp their own message on the text.

The interest of members of the group in the material form of the text also extended to how translations were laid out on the page. Many translations (including some of those discussed above) included additional notes. The 1677 French translation of Rycaut's The Present State of the Ottoman Empire went a step further in having such extensive notes that they had to be added at the end under the heading 'Remarques Curieuses', so as to avoid clogging up the page. This was not always a concern for translators, however. Asaph Ben-Tov mentioned Thomas Erpenius's Historia Josephi, which included both the original Arabic text and not one but two Latin translations all on the same page - a literal interlinear translation and a more Latinate rendering in the margin. As Johann Camman's handwritten comments on his copy of the text make clear, the work was used by Camman as a language-learning tool rather than for its substantive content. This was not unusual in the case of bilingual versions - Alessia Castagnino suggested that the same was true of the bilingual (French and Italian) edition of Pluche's Le Spectacle de la Nature.

Early modern translations, then, served a variety of purposes. The publication arising from the Wolfenbüttel workshops will explore many of these, and I look forward to seeing it come to fruition. At the same time, I am sorry that this means that there are currently no more trips to the beautiful Herzog August Bibliothek scheduled in my diary.