Thomas Hollis and Thomas Spence were very different men, but as readers of this blog will be aware, I have recently been exploring the lives and works of them both.

Thomas Hollis by Joseph Wilton, marble bust, c.1862. National Portrait Gallery, NPG 6946. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

Hollis was born in London on 14 April 1720. His family had made their fortune in the metalworking industry in Yorkshire and had then established a London branch of their cutlery business. Hollis was an only child and was unfortunate in losing most of his close relatives before the age of eighteen. One consequence of this was that by the time he was thirty he was an extremely rich man. Hollis travelled extensively in Europe in the late 1740s and early 1750s before settling in London. Though he briefly toyed with a political career, he soon turned to pursuing politics via other means. Physically, Hollis was described as being over six-feet tall and very strong. He had 'bright brown eyes, a short nose, and laughing mouth' (Colin Bonwick, 'Hollis, Thomas (1720-1774), political propagandist, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 19 May 2025). Hollis retired to his estate in Dorset in 1770, where he died four years later

Profile of Thomas Spence from the Hedley Papers at the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society. Reproduced with kind permission.

Spence was born in Newcastle upon Tyne on 21 June 1750. His father and mother were of Scottish origin and Spence was one of nineteen children. Despite being poor, Spence's father was keen that his sons should learn to read, and by his early twenties Spence was working as a school teacher in Newcastle. He moved to London in early 1788 where he worked as a bookseller for the rest of his life. He produced radical tracts of his own which he sold alongside those by others. The nature of his work got Spence into trouble, and he was arrested on a number of occasions. Physically, Spence was a short man - barely five-feet tall and slightly built. His life-long poverty meant that he was always poorly dressed, and he suffered from both a limp and a speech impediment. Spence was married twice - once in the north east and once in London - but neither marriage was happy. His son William, who moved with him to London, died as a teenager around 1797. Spence himself died in September 1814.

Despite these striking differences in their appearance, backgrounds, and prospects, these two men devoted their lives to very similar activities.

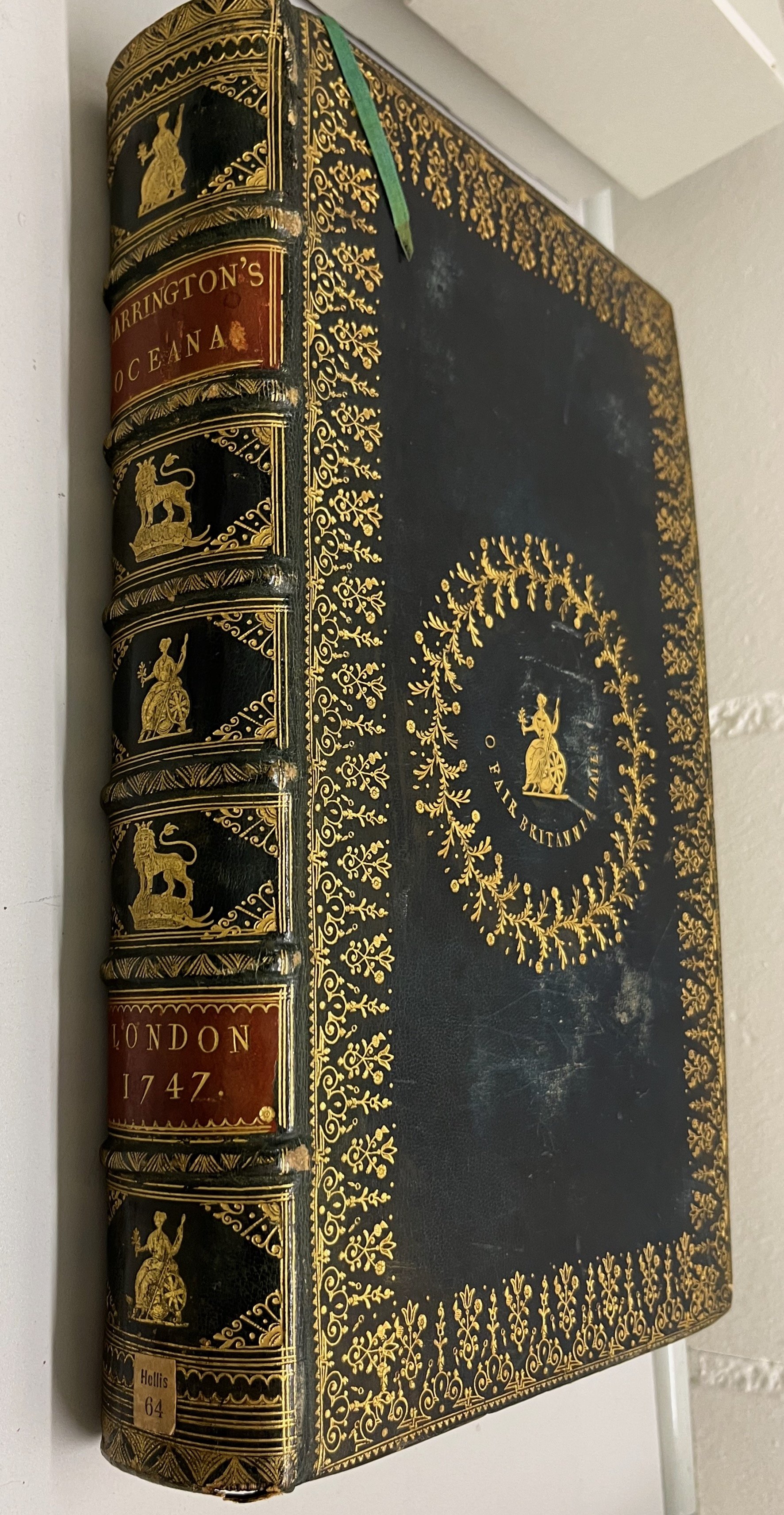

Bern, Universität Bibliothek, ‘Die Hollis-Sammlung’ 64. The Oceana and other works of James Harrington Esq, ed. John Toland (London: A. Millar, 1747). Reproduced with kind permission. Image, Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

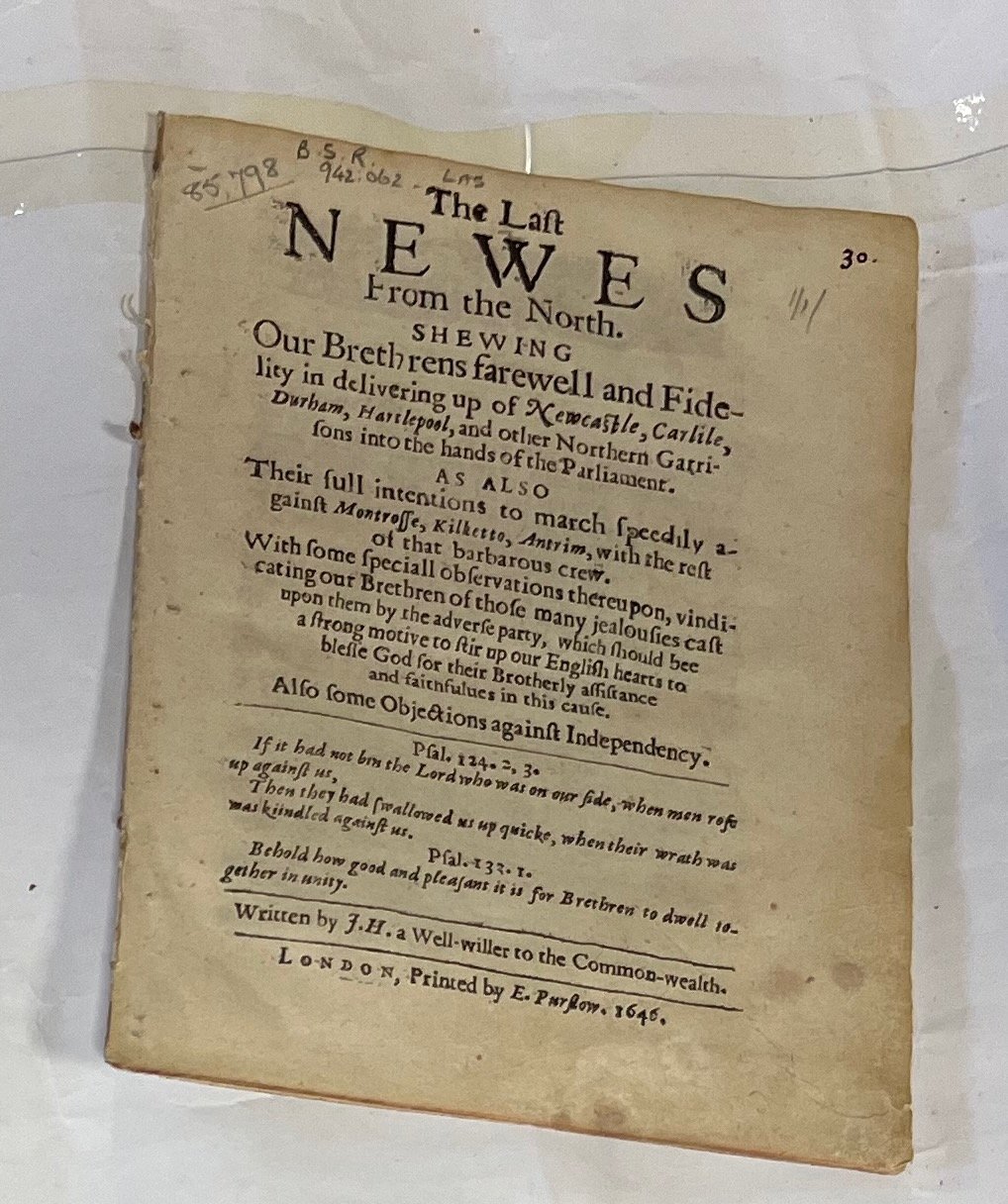

Hollis distributed thousands of books to a range of public and university libraries between 1754 and 1774. Some of the books were simply bought by Hollis in London and sent on. Some had gold tooling added to their front cover or spine, others were specially bound for the purpose. In a small number of cases, the edition itself was commissioned by Hollis before being bound and sent. As a bookseller struggling to make a living, Spence disseminated books but was not in a position to give them away for free. Instead, he offered his own variation on Hollis's project in the form of his journal Pigs' Meat which appeared between 1793 and 1795. Here, for the price of just a penny an issue, readers had access to extracts from a range of texts.

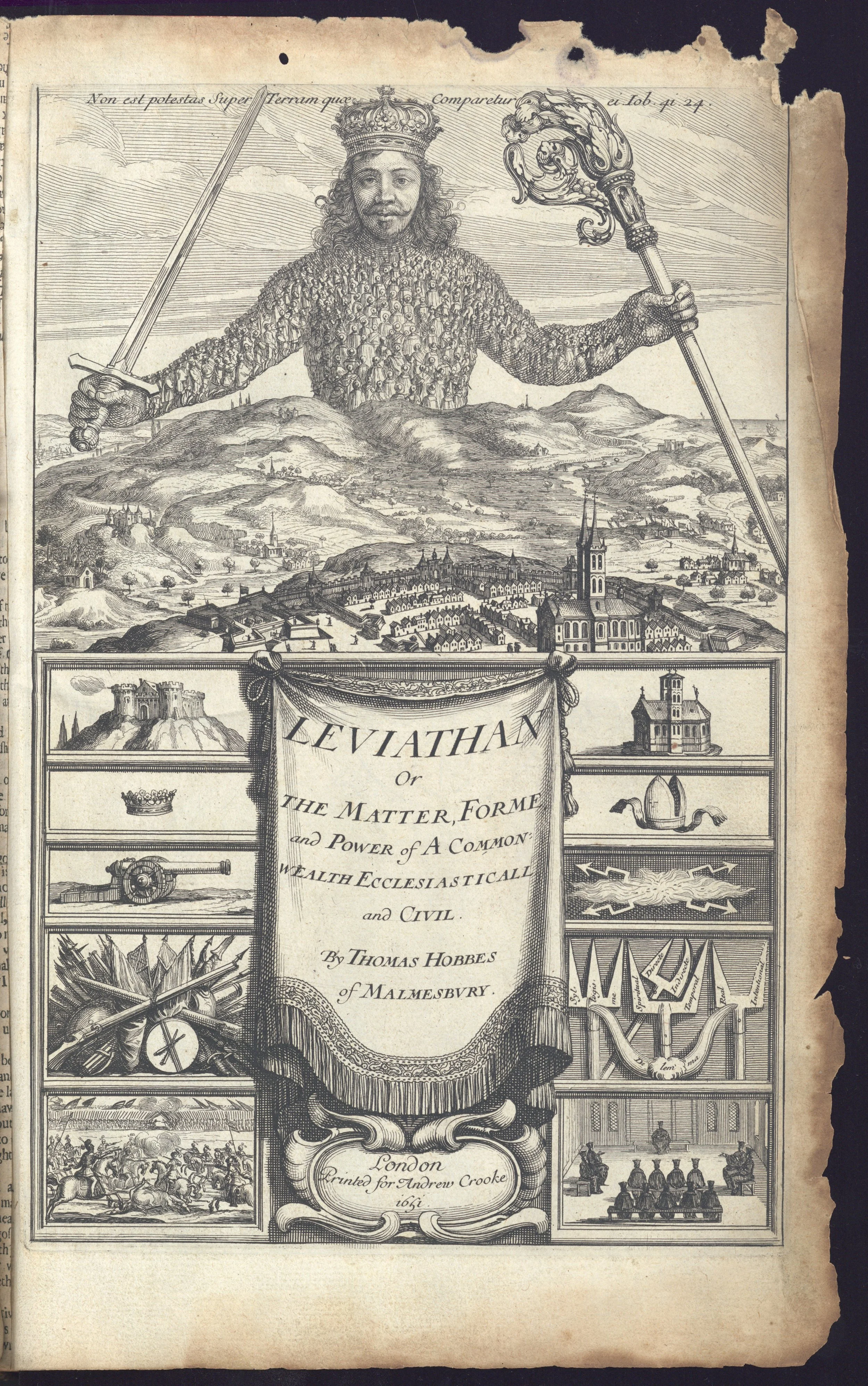

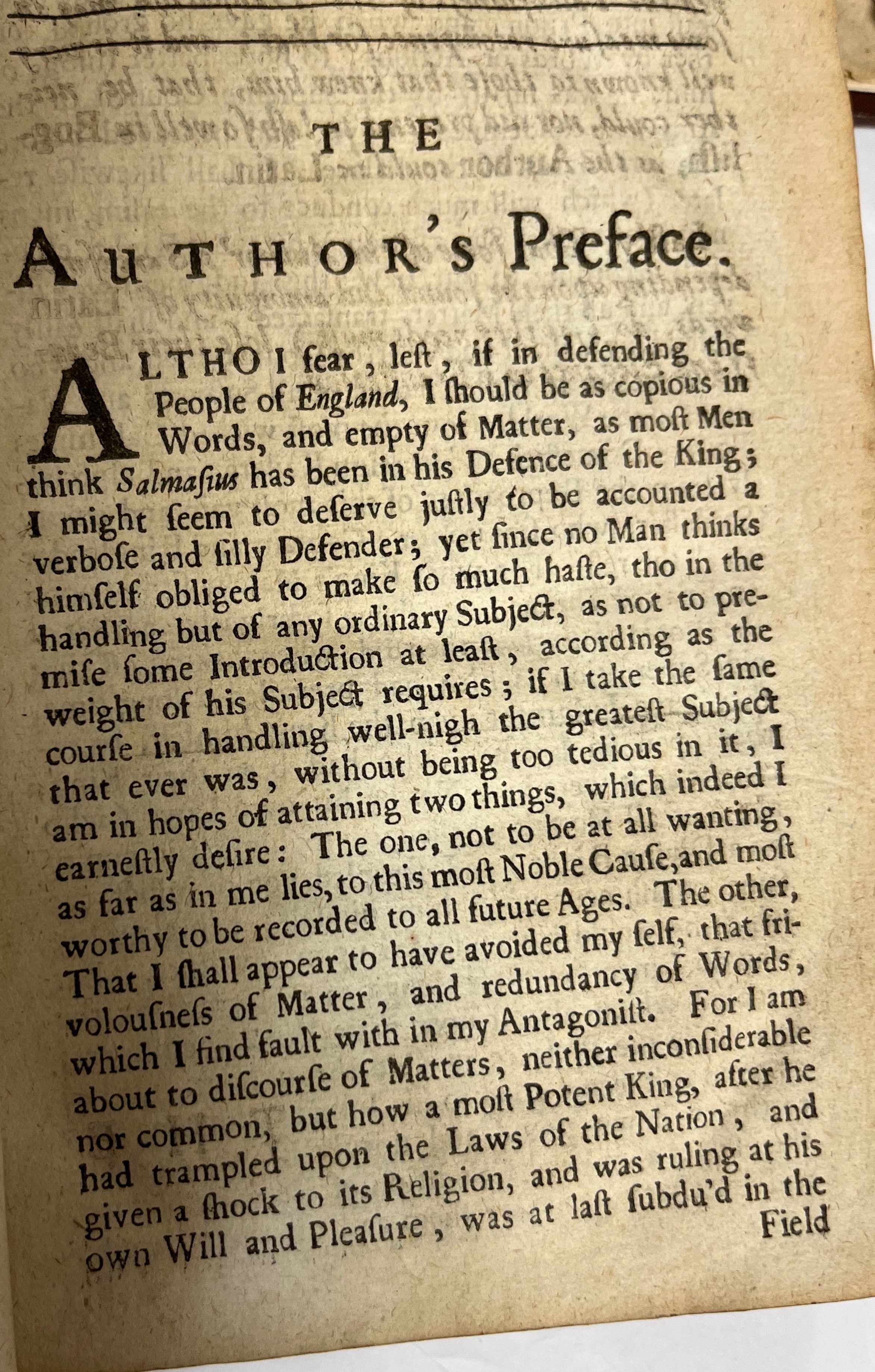

There was significant overlap in the works the two men disseminated. Both focused on politics and religion and had a particular interest in the writings of seventeenth-century republicans, as well as in the eighteenth-century commonwealthmen who applied earlier republican ideas to their own circumstances. The importance of these works to Hollis is reflected in his decision to commission new editions of some of these texts - for example Sidney's Discourses - and in the exquisite bindings of the works of Sidney, John Milton, Edmund Ludlow, and James Harrington that he sent abroad. Spence included extracts from works by Sidney and Milton in Pigs' Meat, but it was Harrington who was the most frequently cited author across the three volumes, closely followed by the commonwealthmen John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon.

The title page of the edition of Sidney’s Discourses commissioned by Hollis with the smoke printed image of the pileus at the bottom. The National Library of Scotland: ([Ac]. 1/1.3]). Reproduced with kind permission. Image, Rachel Hammersley, 2022.

The header to Pigs’ Meat.

Hollis's lavish bindings reflect another parallel between the two men: their concern with the appearance - as well as the content - of works, and their use of symbolic images to convey ideas. Hollis claimed that while he did not value bindings himself, he saw the importance of them in rendering texts of interest to others. There appears to have been some truth in this, since the members of the Council of Bern were persuaded to accept Hollis's donation of books because of the beauty of the volumes. The gold tooling that Hollis added to the cover and spines of the volumes he sent had symbolic meaning - the pileus to indicate liberty, the owl for wisdom, and Britannia for works of patriotic value. Sometimes (for example in the case of the Sidney edition commissioned by Hollis) these symbols were also smoke printed onto the page. Once again, Spence's poverty meant he did not have the same opportunities available to him. Yet the pig image used on the title page of the second edition of Pigs' Meat served a similar purpose. Moreover, it too included a pileus or liberty bonnet that closely resembled that used regularly by Hollis.

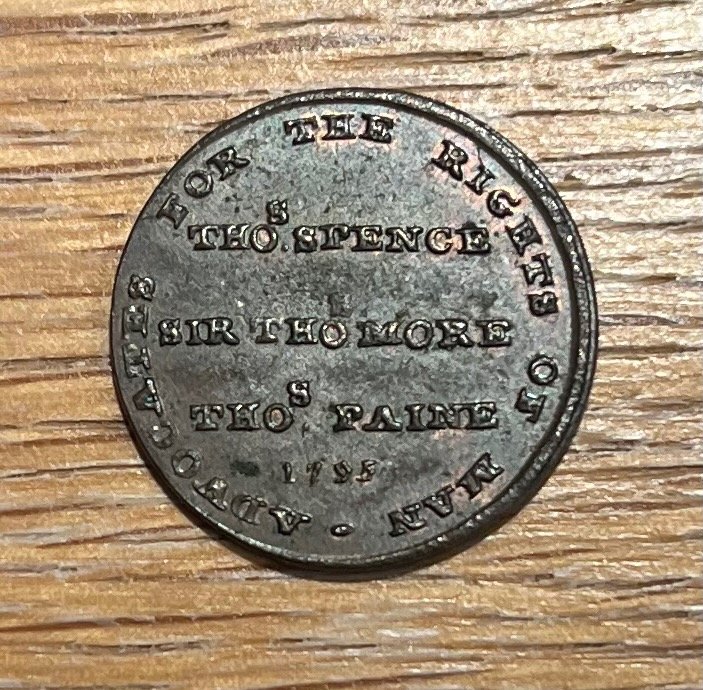

The Three Thomases coin owned by the author. Image, Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

Both men also conveyed their political messages in metal as well as print. Hollis bought, commissioned, and disseminated medals alongside books. Spence described himself as a 'Dealer in Prints & Coins' and designed his own tokens - including one depicting three Thomases (though sadly Hollis was not one of them). Moreover, while Spence could not afford to give books away, a contemporary claimed that he tossed tokens out of the window and that passers by who picked up a token could then exchange it at his shop for a pamphlet (British Library: Add. MS. 27,808, 184). He also gave away a token free with each copy of the first issue of his final periodical The Giant Killer or, Anti-Landlord.

Despite their differences, then, both Spence and Hollis made extensive efforts to disseminate political ideas to a wide audience. Moreover, they did so because they believed that this would bring wider societal benefits. While there were differences in their political perspectives, they were both committed to ensuring that the public had access to republican ideas and those in support of liberty and rights. This was reflected in the dedication Hollis used in various forms in the works he donated:

Thomas Hollis, an Englishman, a Lover of

Liberty, his Country & its excellent

Constitution as NOBLY restored at the happy

Revolution, is desirous of having the

honor to present Milton's Prose Works to the

Public Library of Harvard College, at

Cambridge in New England.

Pall Mall, oct. 14, 1764 (Bond, p. 135).

An Englishman, a lover of liberty, civil & religious, Citizen of the World, is desirous

of having the honor to present this book to the public library at Berne in

Switzerland.

London jan 1, 1765. (Bern, Universität Bibliothek, 'Die Hollis-Sammlung' 71).

Elsewhere he explained that he sent books on government: 'for, if Government goeth right, ALL goeth right.' (Bond, p. 34).

On the title page to Pigs' Meat, Spence asserted a similar aim. The works collected in the periodical were designed, he explained:

To promote among the Labouring Part of Mankind proper Ideas of their Situation,

of their Importance, and of their Rights. And to convince them That their forlorn

Condition has not been entirely overlooked and forgotten, nor their just Cause

unpleaded, neither by their Maker nor by the best and most enlightened of men in

all Ages. (Thomas Spence, Pigs' Meat, Volume 1. London, 1793, Title page).

There might be a temptation to dismiss both Hollis and Spence as at best naïve and at worst eccentrics or cranks. Yet it is hard to deny that informed citizens are necessary for the preservation of liberty and the successful functioning of democracy. It is especially important to remember this at the present time when education seems to be under threat from all directions - from cuts in school budgets to threats of compulsory redundancies in higher education. I suspect that Hollis and Spence would be appalled.