Ever since I volunteered, as an undergraduate, in the Coins and Medals Department of the British Museum, I have been interested in how complex ideas can be presented effectively to the general public. As a volunteer I sat in on an initial meeting to discuss plans for what would become the permanent Money Gallery. I remember the excitement of thinking about how to convey centuries of history accurately - but also accessibly - with a restricted number of objects and very little text. Though I ended up becoming an academic rather than a curator, that challenge has always appealed to me. For this reason, when applying for funding for the Experiencing Political Texts project, I was keen to include an exhibition as one of our outputs. In the end we decided to offer two - one at the Robinson Library at Newcastle University and another at the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh. The former opens this month and in this blogpost I hope to encourage you to visit the exhibition by providing a taste of its content.

Encountering Political Texts

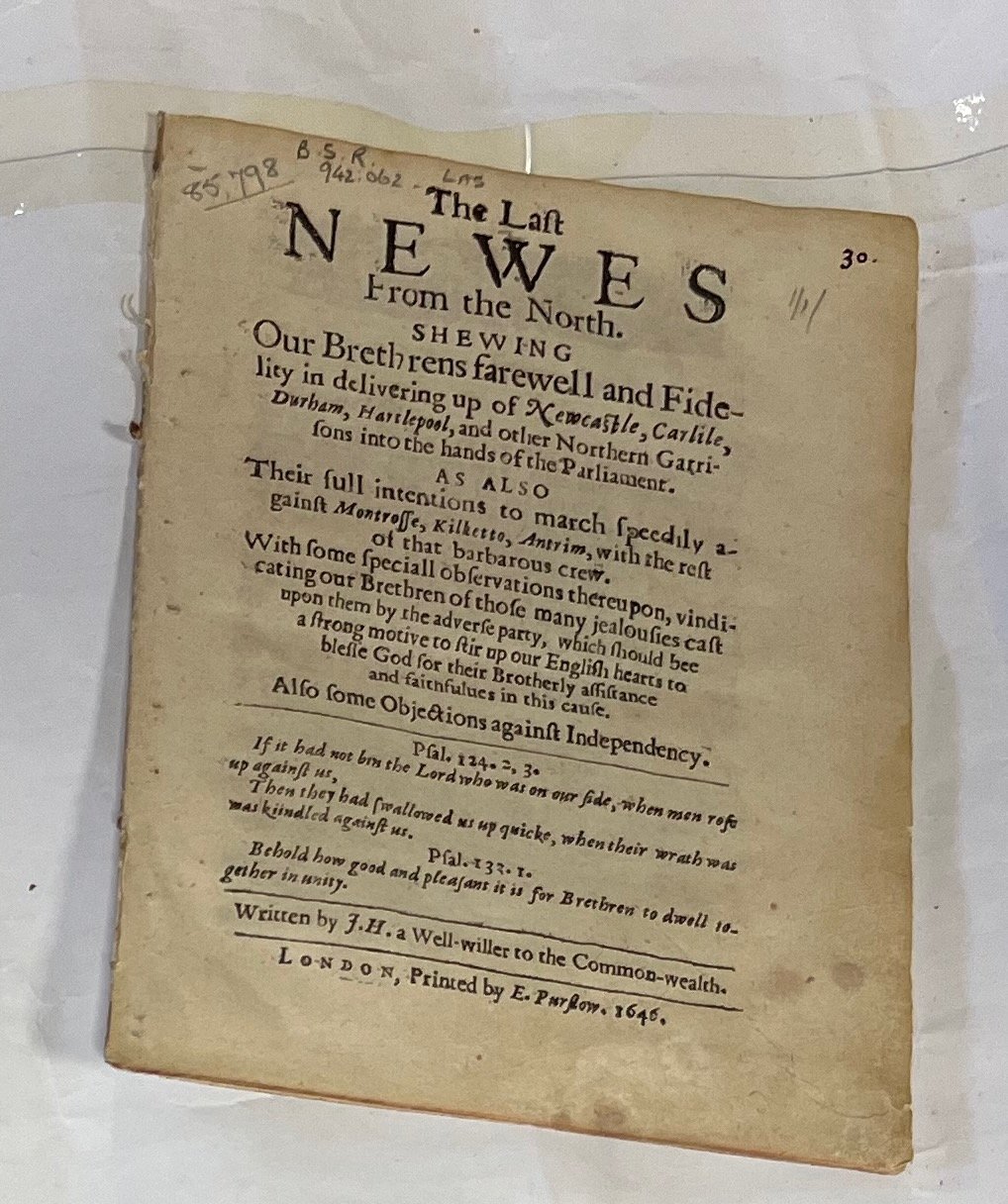

An unbound pamphlet The Last Newes from the North (London, 1646). Newcastle University, Robinson Library, Rare Books: RB 942.062 LAS.

How do we encounter political ideas and information? How did early modern people do so? And what do we make of their political texts? A work like Robert Filmer's Patriarcha, a daunting volume that argues the case for the divine right of kings on the basis that all kings are descended directly from Adam, is likely to feel very alien and inaccessible to a modern audience. The regular use of Latin phrases, the grounding in Biblical learning, the long unwieldy sentences, the use of the long 's' (which looks like an 'f') all conspire to put the modern reader off. Filmer's text is still read today (indeed it appears in Cambridge University Press's 'blue text' series in an edition produced by Johann Somerville in 1991) and it has been the subject of an important recent monograph by Cesare Cuttica. Yet its survival owes less to its relevance today than to the fact that it acted as a provocation to at least three important political texts of the 1680s: James Tyrell's Patriarcha non Monarcha (1681); John Locke's Two Treatises of Government (1690) and Algernon Sidney's Discourses Concerning Government (1699).

Of course, not all early modern political texts took the form of, often lengthy, books. During the turbulent period of the British Civil Wars politics was increasingly conveyed to a wider public via newsbooks (the forerunner of the modern newspaper), pamphlets (short cheap publications usually engaging with a specific political issue), broadsides (a single page that was designed to be posted up on a wall), and even ballads (political songs). There were, therefore, lots of opportunities for people - even those with limited literacy - to gain political knowledge and engage with current affairs.

The Physical Book

A central theme of the Experiencing Political Texts project has been the idea that books are physical objects and that their materiality can contribute directly to their argument. Paying attention to features such as the the size, paper quality, typeface, and ink can contribute to our understanding of the message the author was seeking to convey and how it might have been received by readers. Moreover, changes in these features in different editions of a particular work can transform the reading experience and how the work is interpreted and understood. In the exhibition we explore these issues by displaying alongside each other several different versions of James Harrington's The Commonwealth of Oceana.

The Imagery of Politics

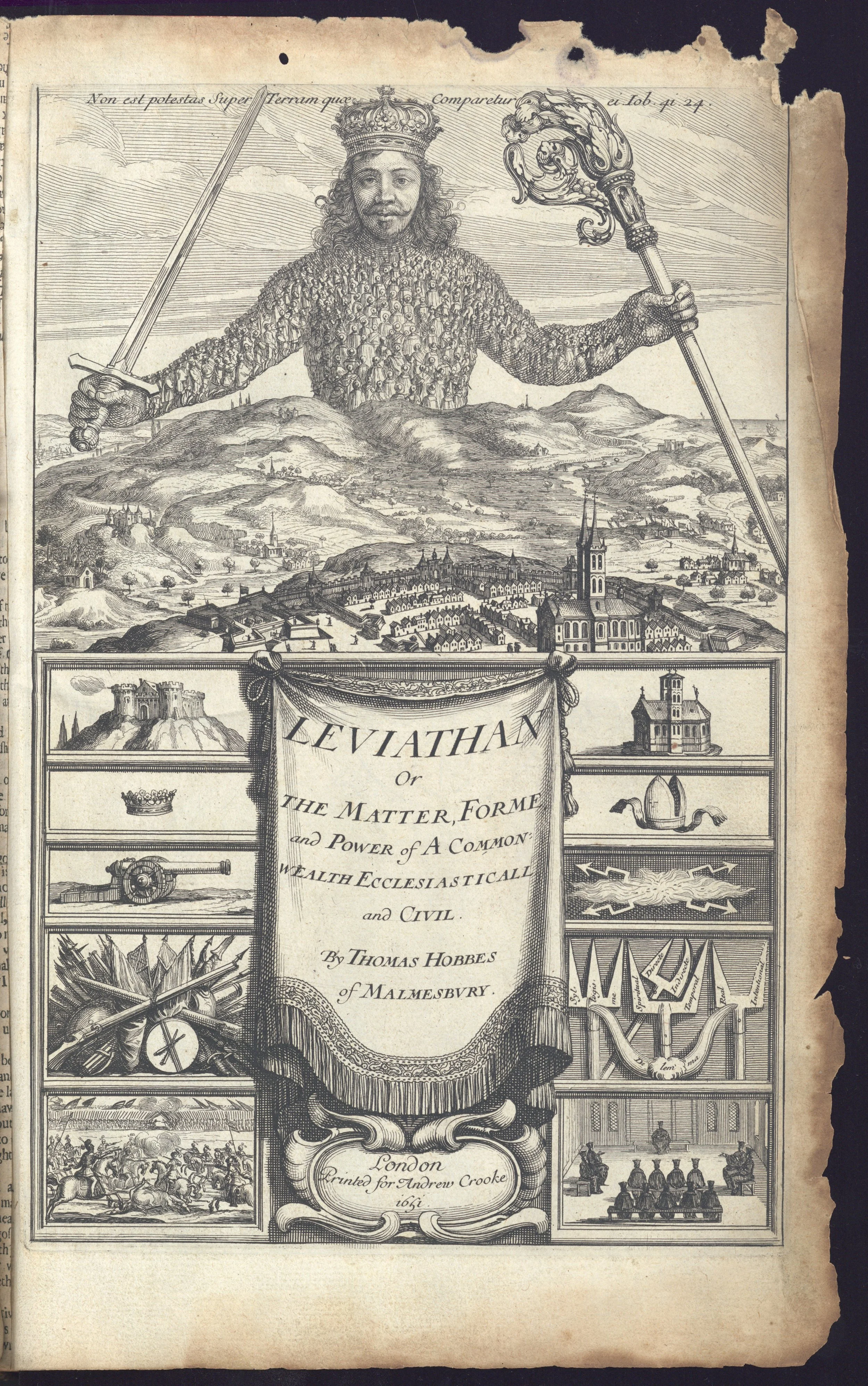

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (London, 1651), frontispiece. Newcastle University Special Collections and Archives, Bainbrigg: BAI 1651 HOB.

Authors can use images as well as words to convey their ideas to readers. Some early modern books (especially expensive volumes) began with a frontispiece illustration that conveyed the argument of the book in visual form. The exhibition includes two early examples of this: Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan and the Eikon Basilike. It also considers what authors did to present their argument succinctly when they could not afford a fancy illustration.

Editing Political Ideas

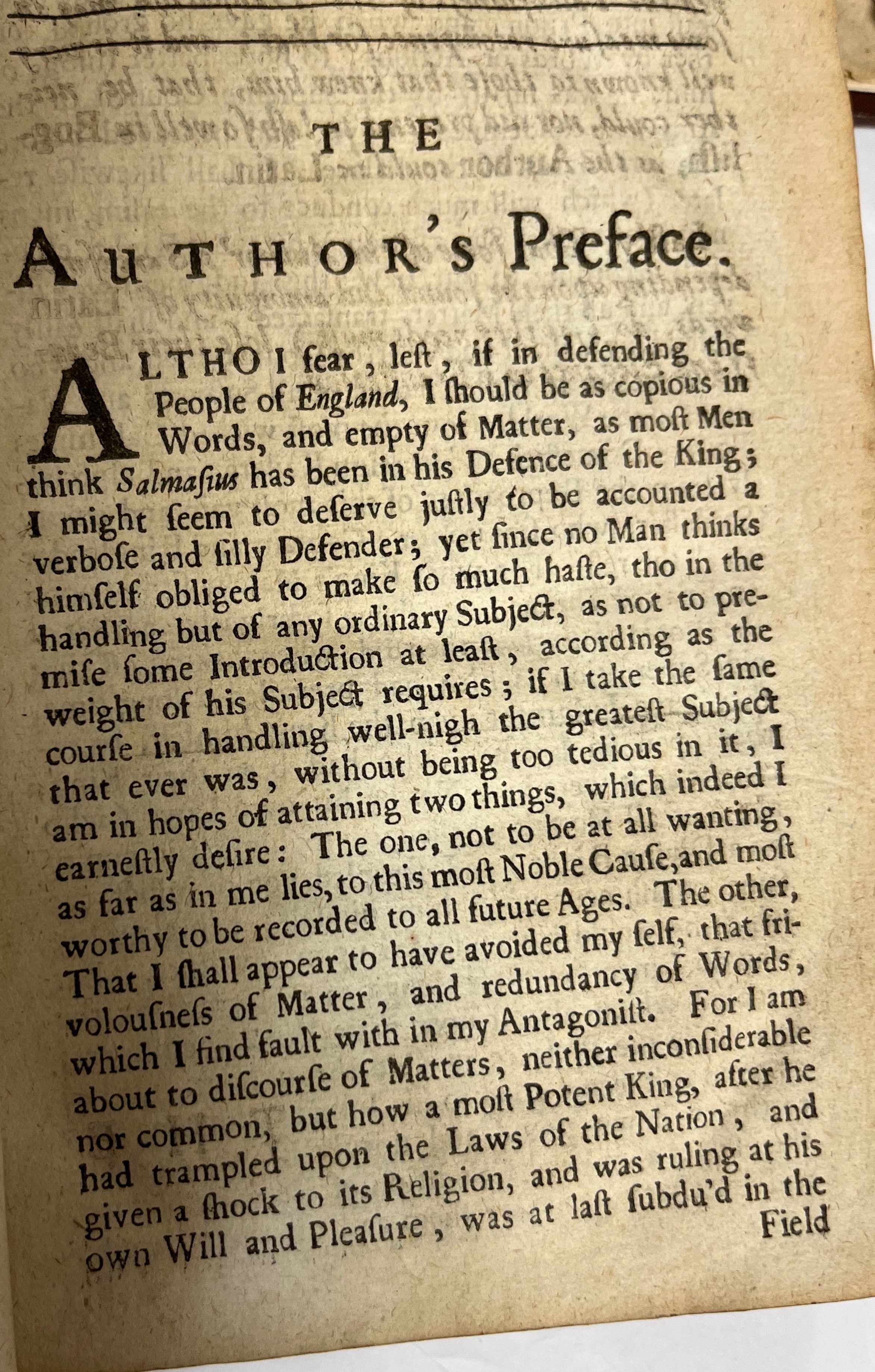

The Author’s Preface to John Milton, A Defence of the People of England, ed. Joseph Washington (Amsterdam, 1692). Newcastle University, Robinson Library, Bainbrigg: BAI 1692 MIL.

Important political texts tend to survive beyond their immediate context and might be reissued multiple times. Though the text itself usually remains relatively stable, editors will adapt the size, quality, and design to suit their intended audience and may also add paratextual material to make the text accessible to contemporary readers or to demonstrate the relevance of the ideas to the times. The exhibition uses editions of John Milton's prose text Pro populo anglicano defensio (A Defence of the People of England) to demonstrate just how an editor can influence how a text might be approached and read.

Editing Ancient Politics

Of course, early modern editors also produced their own editions of older texts, especially those from ancient Greece and Rome, which were viewed as providing important insights on political matters. As with editions of contemporary texts, decisions about design and production were used to direct the work to particular audiences and to influence how it was read. In particular, there is a distinction to be drawn between works aimed specifically at learned readers and those intended for wider consumption.

Politics in Periodicals

Periodical publications were one of the success stories of the eighteenth century. The number of titles expanded rapidly and their format and relatively low cost made them accessible for those beyond the political élite, including artisans and women. While part of their aim was to entertain, many also included a philosophical, moral, or political dimension, prompting us to ask whether these count as 'political' texts.

Thomas Spence’s periodical Pigs’ Meat, or Lessons for the Swinish Multitude (London, 1793-1795). Newcastle University, Robinson Library, Rare Books: RB 331.04 PIG.

Conversations in Print

Some periodicals also encouraged debate - inviting readers to respond to articles via letters or essays of their own. This idea of print as a forum for debate was also reflected in the 'pamphlet wars' of the early modern period in which two or more authors debated a particular issue or issues. The exhibition provides examples of both exchanges that occurred quickly, within a matter of weeks, and those that occurred over a longer period of time.

Experiencing Political Texts

Ultimately our aim is to encourage visitors to think more deeply about the nature of political texts. What makes a text political? How does its physical form contribute to that characterisation? We might even ask what constitutes a text? We are also keen to encourage people to think about how the form in which they read a work affects the reading experience. The experience of reading a text digitally on a screen is different from reading the same text in hard copy. But equally, reading an original edition of an early modern text is a different experience from reading a modern edition. It is even the case that reading an original edition today is different from the experience of reading it when it was initially produced. Finally, does this lead us to think differently about how we engage with politics today?