The National Library of Scotland. Image by Rachel Hammersley

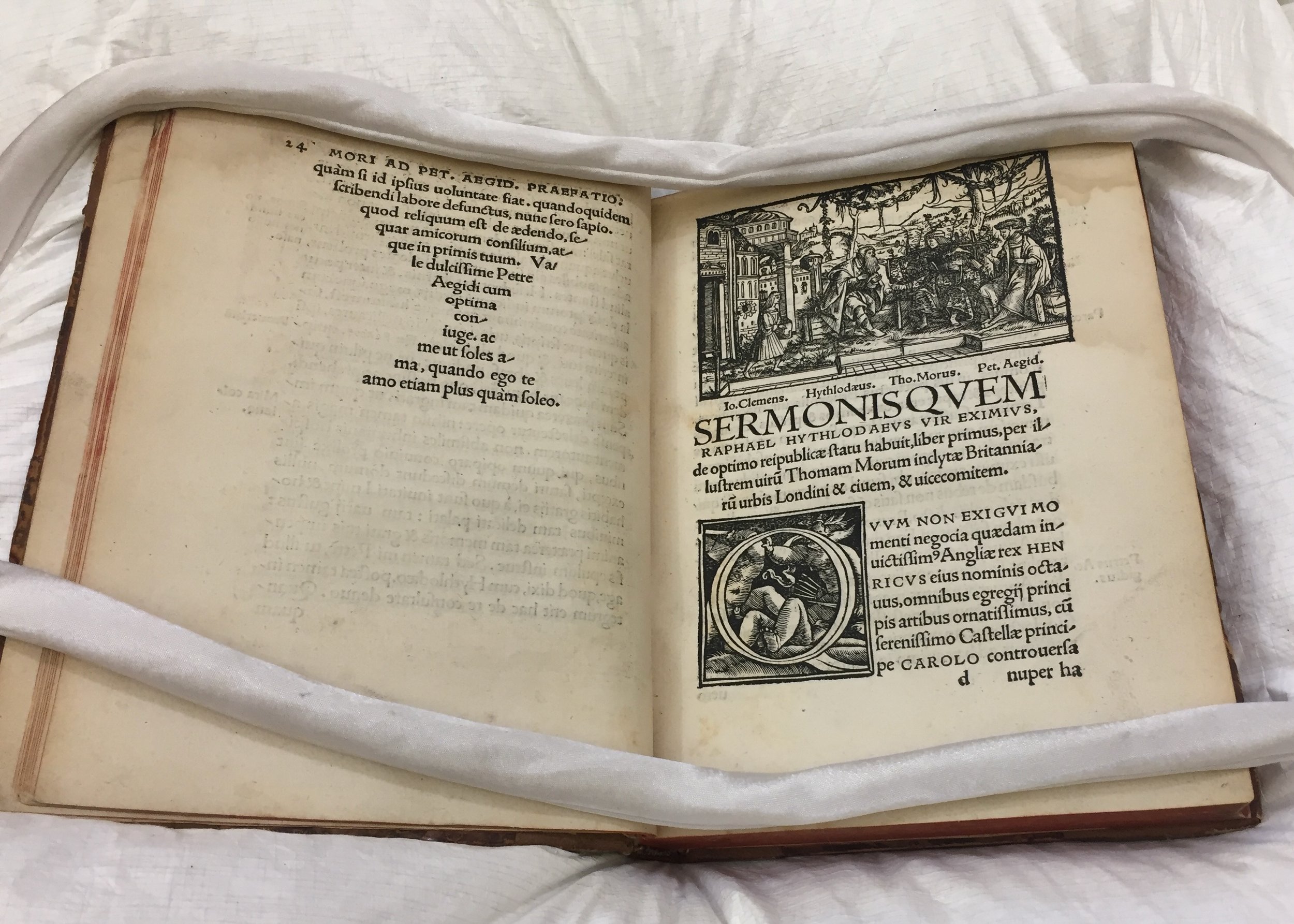

Next week the exhibition 'Encountering Political Texts' opens at the National Library of Scotland (NLS). This is the second exhibition related to the 'Experiencing Political Texts' project (an account of the first, which was held at Newcastle University's Philip Robinson Library last summer, can be found here). It is also our final Experiencing Political Texts event. Though the general themes are similar to those in the Newcastle exhibition, the focus of each cabinet and the items on display are different. Next month's blog will offer a full account of the exhibition, this month I provide a quick taster, discussing what are perhaps my favourite items in the exhibition - the volumes produced by Thomas Hollis.

I have discussed Hollis in previous blogs, and so will not repeat those details here. Instead I will focus on the volumes in the NLS collection, some of which feature in our exhibition. These volumes originally formed part of the Advocates Library of Edinburgh. This was a law library that was officially opened in 1689. From 1710 it became a legal deposit library, meaning that it received a copy of every book published in the United Kingdom. Between 1752 and 1757 the Keeper of the Advocates Library was the philosopher and historian David Hume. In 1925 the National Library of Scotland was created by an Act of Parliament

Hollis made donations to the Advocates Library at various points during the 1760s and 1770s, at a time when he was also sending books to Oxbridge college libraries and to public and university libraries in Europe and North America. Many of the NLS Hollis volumes include a dedication, written in Hollis's hand. Though the messages vary slightly from copy to copy the basic formula is this:

Henry Neville, Plato Redivivus, or a dialogue concerning government (London, 1763). National Library of Scotland: ([Ad]. 7/1.8). Image credit: National Library of Scotland.

An Englishman, a lover of liberty, citizen of the world, is desirous of having the

honor to present this to the Advocate's Library at Edinburgh.

Henry Neville, Plato Redivivus, or a dialogue concerning government (London, 1763). National Library of Scotland: ([Ad]. 7/1.8). Reproduced here under a Creative Commons License with permission from the Library

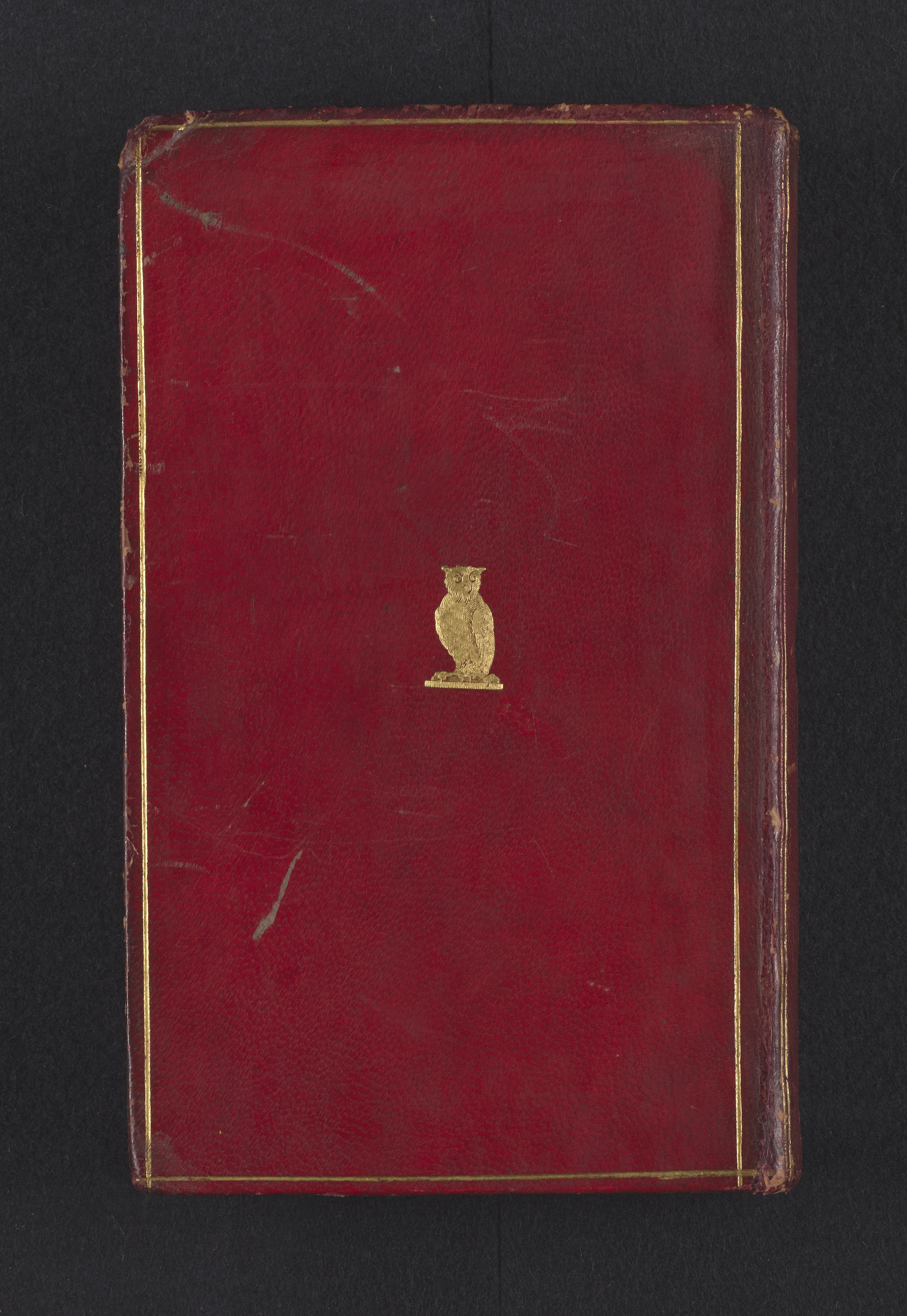

Most of the Hollis volumes at the NLS are bound in red Morocco with symbols added to the cover in gold tooling and stamped in black ink on the inside pages. They were the work of John Matthewman, who was Hollis's main bookbinder until around 1769 when he absconded due to a debt.

Henry Neville, Plato Redivivus, or a dialogue concerning government (London, 1763). National Library of Scotland: ([Ad]. 7/1.8). Image credit: National Library of Scotland.

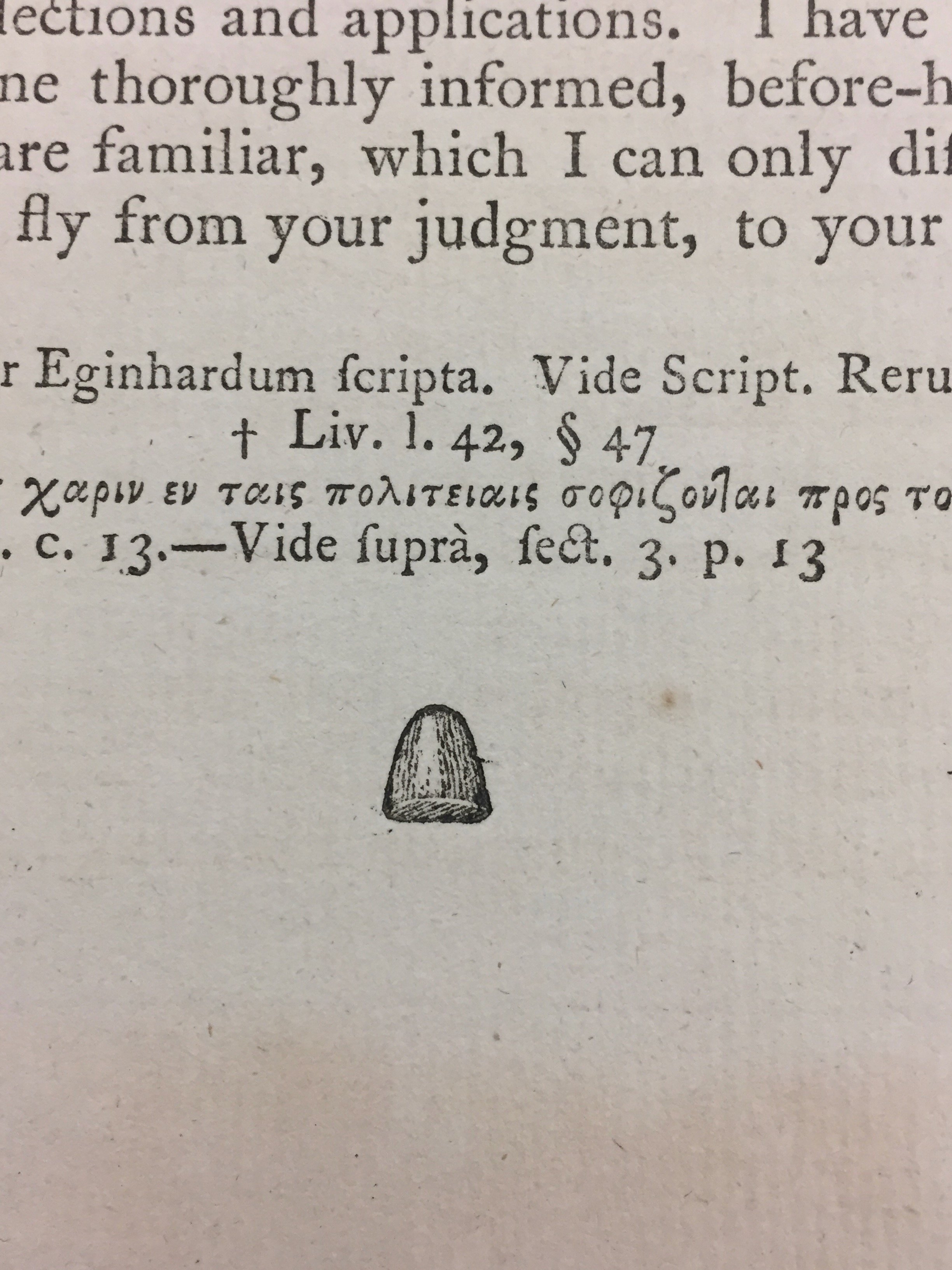

Among the volumes sent to the Advocates Library were several works from the commonwealth tradition. These include Henry Neville's Plato Redivivus, which had first appeared in 1681 at the time of the Exclusion Crisis. It sought to apply the principles set out by Neville's friend James Harrington in The Commonwealth of Oceana (1656) to the very different political situation of the 1680s. The work was republished by Andrew Millar in 1763. Hollis seems to have been quick to call for a second edition since an entry in Hollis's diary for 15 November the following year records a conversation Hollis had with Millar in which he 'Engaged him to reprint, that master-work intitled "Plato Redivivus. Or a Dialogue concerning Government", written by Harry Neville the friend of James Harrington, and like him ingeneous.' (The Diary of Thomas Hollis V from 1759 to 1770 transcribed from the original manuscript in the Houghton Library Harvard University, ed. W. H. Bond. Cambridge, Mass., 1996. 15 November 1764). The dedication in the Neville volume is a little fuller than the basic version reproduced above, with Hollis declaring himself a lover not merely of liberty but also of 'the Principles of the Revolution & the Protestant Succession in the House of Hanover'. The tools on the cover of this volume are a cockerel on the front and an owl on the back, with a Pilius (liberty cap) on the spine. The cockerel symbolises alertness or vigilance, the owl - wisdom, and the Pilius - liberty. Inside the volume is a stamp depicting Athena (the Greek goddess of wisdom) and one of Britannia (NLS: [Ad].7/1.8).

Also in the collection, though not in an original Hollis binding and probably not donated by Hollis himself, is a copy of Algernon Sidney's, Discourses Concerning Government. First published in 1698 by John Toland, the volume was reprinted several times during the eighteenth century with additional material being added each time. The copy in the NLS is a 1772 reprint of the 1763 edition printed by Andrew Millar that was edited by Hollis and which marked the high point of the work in terms of size, incorporating a biography of Sidney, additional works by him, and letters taken from the Sidney papers. This version includes an Advertisement signed by J. Robertson and dated 21 October 1771, which explains that various corrections (not previously picked up) had been made regarding the names old English names and places. The volume also includes the famous engraving of Sidney that Hollis commissioned from Giovanni Cipriani in which Sidney is dressed in armour and enclosed within a laurel wreath. Below that image, and repeated on the title page and later in the work, is a small Pilius, highlighting Sidney's commitment to liberty.

John Milton, The Life of John Milton (London, 1761). National Library of Scotland, Dav.1.2.10. Image credit: National Library of Scotland.

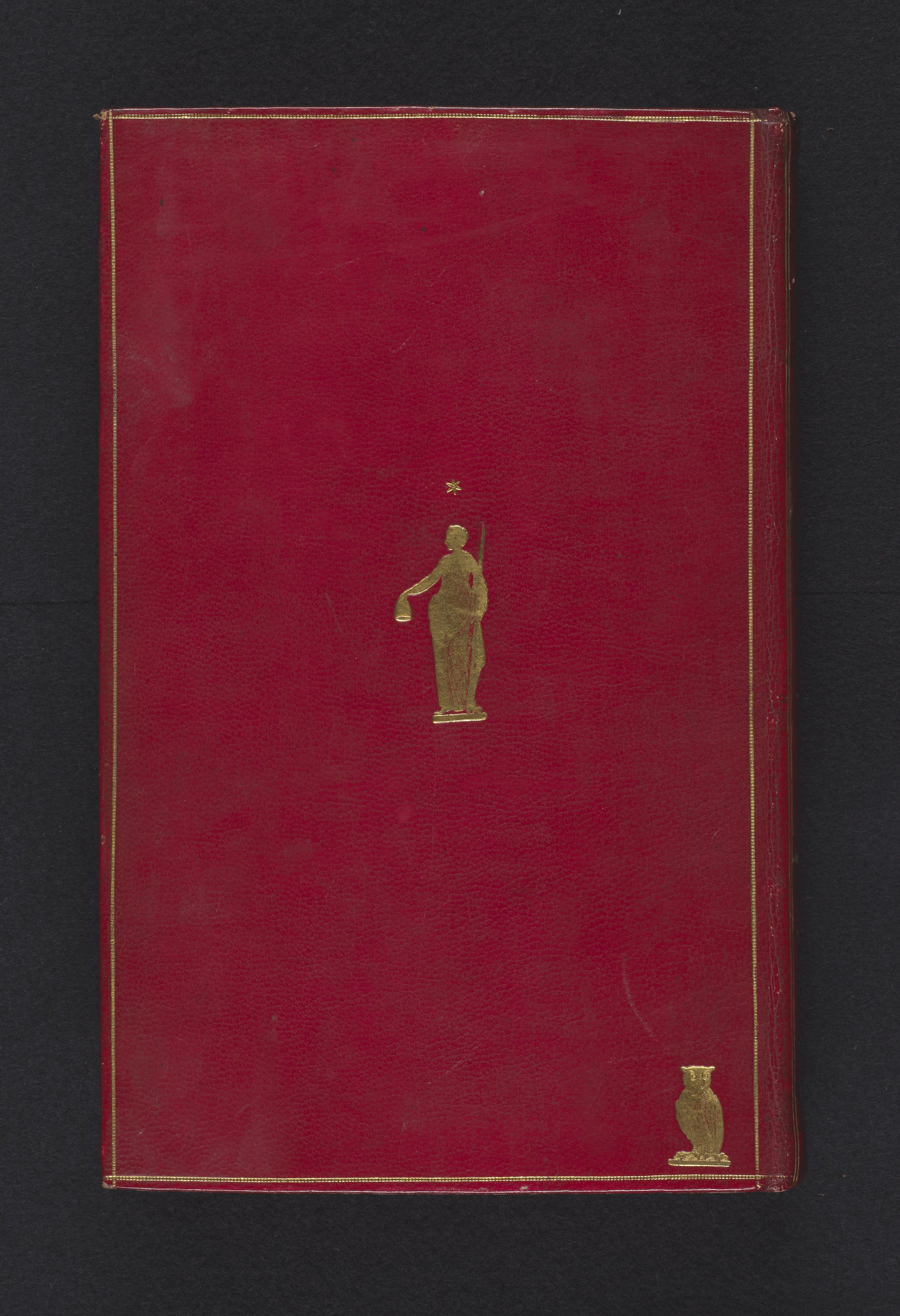

As well as publishing the first version of Sidney's Discourses, Toland had also published the works of John Milton in 1698. To accompany this, he wrote and printed The Life of John Milton which was then reprinted by Millar in 1761. This was another of the works that Hollis sent to the Advocates Library in the 1760s. It is particularly interesting because it has not one but three gold tools on both the front and the back. On the front is Athena with a branch on one side of her and a feather on the other. On the back the cockerel, Britannia, and the owl. The proliferation of gold tooling perhaps reflects the particularly high esteem in which Hollis held Milton. Hollis referred to Milton as 'divine' and 'incomparable'. And as well as collecting and disseminating Milton's works, Hollis had a picture of him in his apartment and even managed, in 1760, to purchase 'a bed which once belonged to John Milton, and on which he died'. This he sent as a present to the poet Mark Akenside, suggesting that if 'having slept in that bed' Akenside should be prompted 'to write an ode to the memory of John Milton, and the assertors of British liberty' it would be sufficient recompense for Hollis's expense (Memoirs of Thomas Hollis. London, 1780, pp. 93, 104, 112).

Following J. G. A. Pocock, a sharp distinction has tended to be drawn between the commonwealth writers (including Milton, Sidney and Neville) and John Locke. Now much questioned, this distinction also does not appear to have existed for Hollis who felt quite able to celebrate Locke as well as Milton. Several copies of Locke's works appear among the Hollis volumes in the NLS. One of these (a copy of the 1764 edition of Two Treatises of Government produced by Millar) resembles the commonwealth works in depicting Athena on the front and the Pilius on the back (with stamps of a Harp and Britannia on the fly leaves). Another emphasises the association of Locke's works with liberty by repeatedly using the Pilius image (NLS: [Ac].4/1.7).

Finally, several of the volumes donated by Hollis to the Advocates Library focus on religious rather than political matters, including several by the clergyman and religious controversialist Francis Blackburne (1705-1787). Born, like Hollis himself, in Yorkshire, Blackburne lived most of his life in Richmond. Though he became a clergyman in the Church of England, Blackburne subsequently refused to subscribe again to the Thirty-nine Articles, the defining statement of the doctrines and practices of that Church. His best known work The Confessional (which Hollis had persuaded him to publish and to which he gave his commendation 'Ut Spargum' - that we may scatter them) engaged with the history of the Church of England and the controversies over subscription. It was a text that prompted a fierce pamphlet exchange, allegedly amounting to ten volumes worth of material (B. W. Young, 'Blackburne, Francis', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). The presentation copy of The Confessional that Hollis gave to the Advocates Library bears a stamp of Athena inside the front cover and one of an owl in the back. The front bears a gold tool of Caduceus or staff of Hermes, a symbol of peace and rebirth, and the back a gold-tooled branch with leaves (NLS: Nha.Misc.32).

Francis Blackburne, Considerations on the present state of the controversy between the Protestants and Papists of Great Britain and Ireland (London, 1768). National Library of Scotland: Nha.Misc.31. Image credit: National Library of Scotland.

Hollis also presented a copy of Blackburne's Considerations on the present state of the controversy between the Protestants and Papists of Great Britain and Ireland (1768) which, like the Milton volume, bears more than one emblem on the front and back covers. In the centre of the front cover is a gold-tooled Britannia, with a cockerel placed in the bottom left corner. The back depicts Athena centrally with an owl bottom right. The spine features the Caduceus (Nha.Misc.31).

Though he remained within the Church of England, Blackburne had close family connections to Theophilus Lindsey and John Disney who were involved in the establishment of Unitarianism, suggesting a link to Hollis's own Dissenting position. Moreover, just as Hollis devoted his life to preserving the memory of great thinkers of the past and present, so Blackburne played a crucial role in preserving the memory of Hollis himself. Following his friend's death, Blackburne produced a two-volume account of Hollis's life, which has been described as a 'memorial to Hollis's radical tradition' (Young, 'Blackburne, Francis', ODNB).

A number of the Hollis volumes described in this blogpost will be on display at the 'Encountering Political Texts' exhibition at the National Library of Scotland between Friday 8th December 2023 and Saturday 20th April 2024.