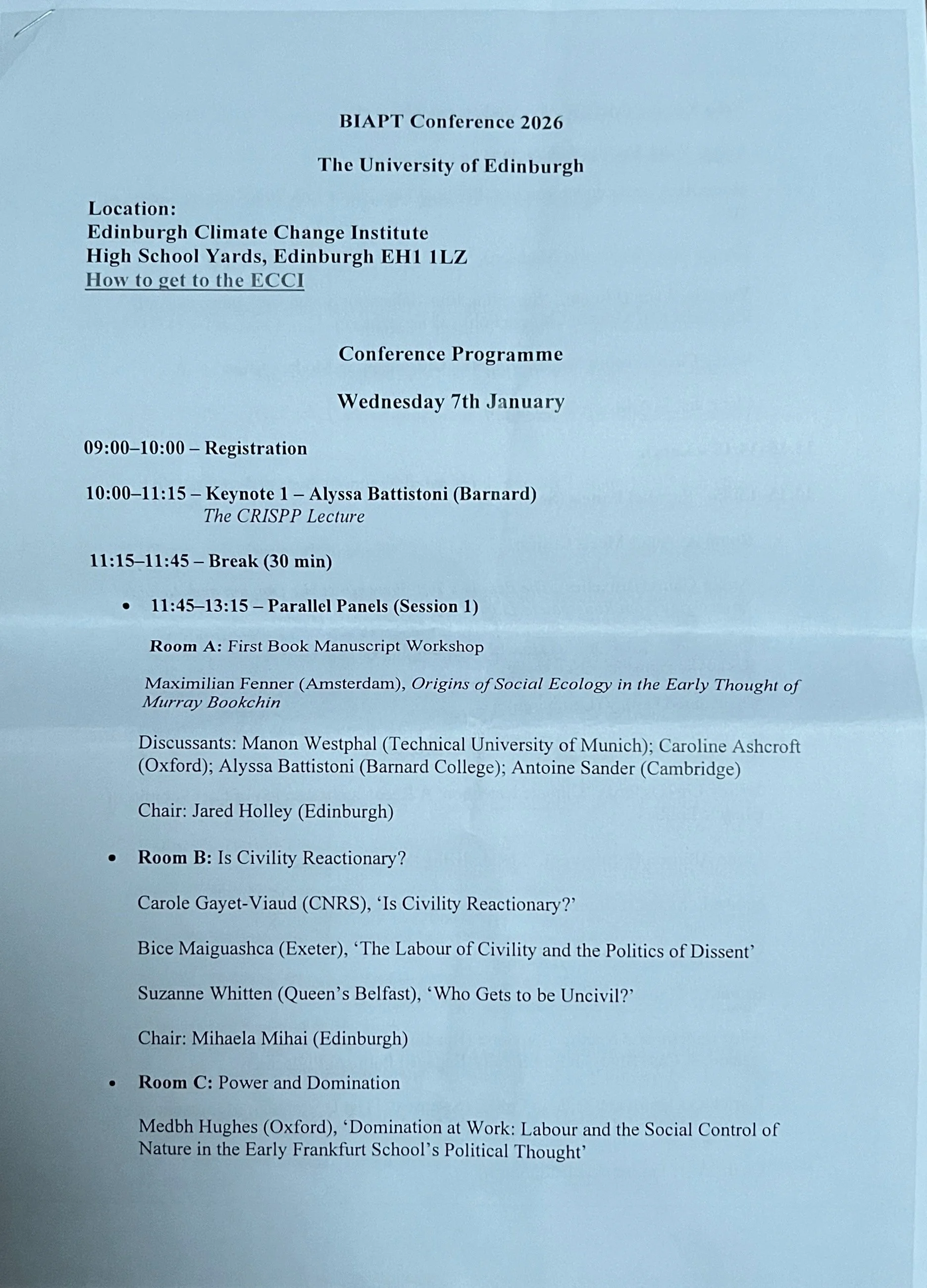

Edinburgh Climate Change Institute. Image Rachel Hammersley

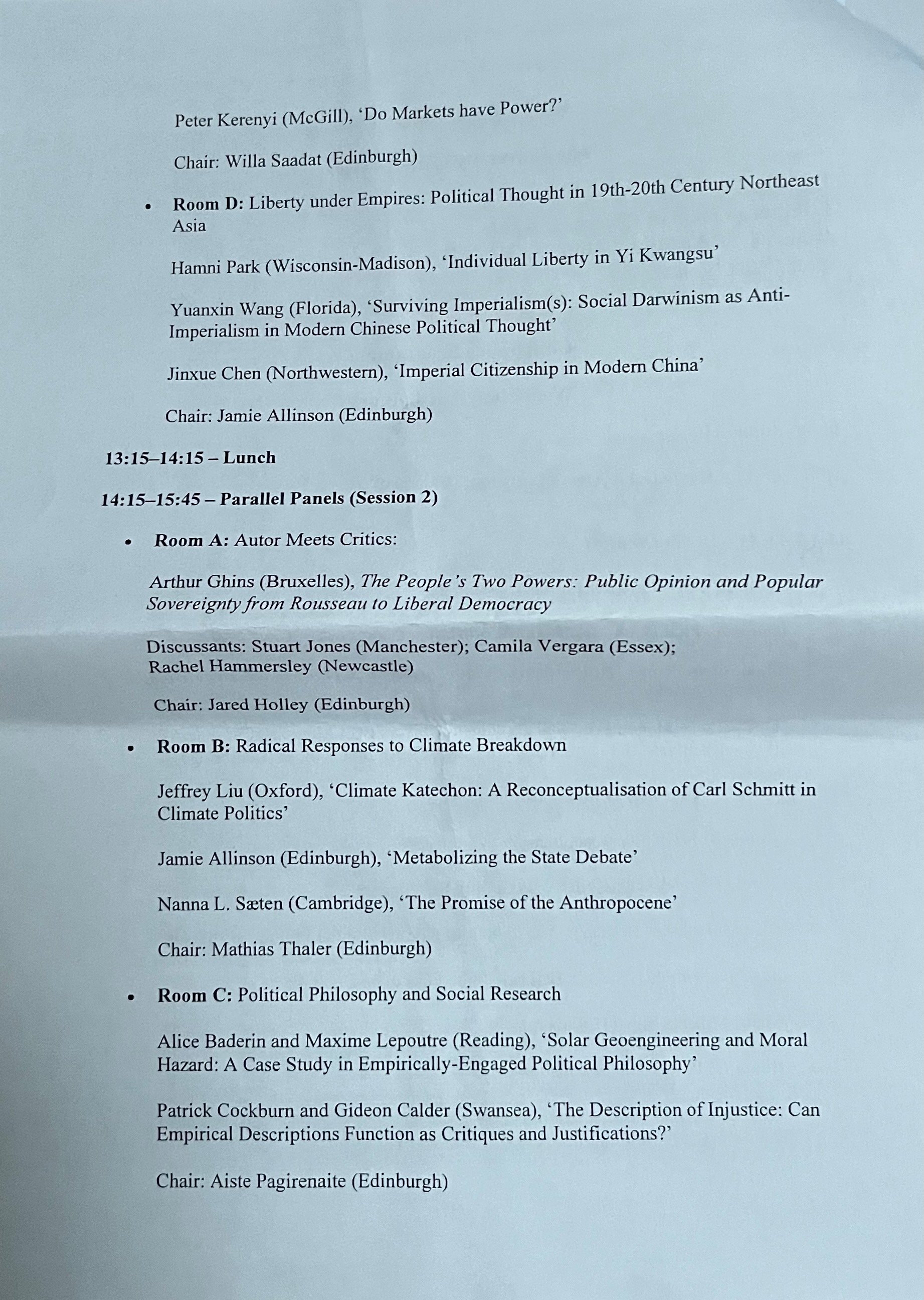

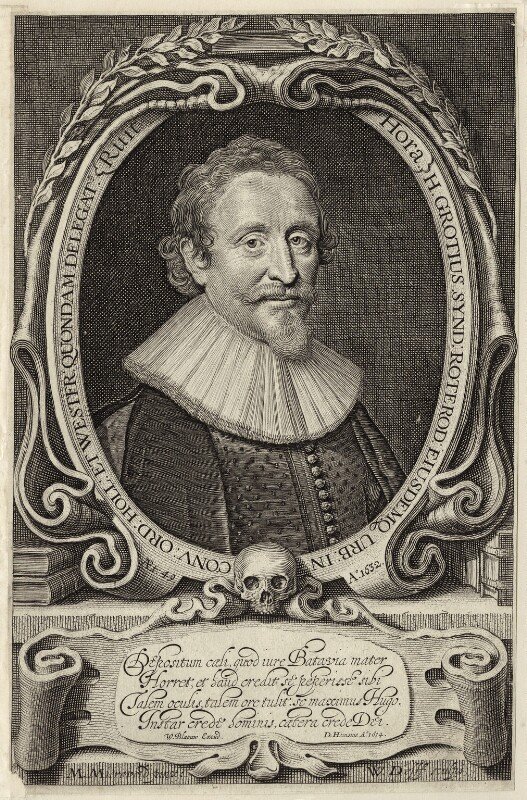

On a dark and bitterly cold morning in January I literally slipped and skidded down my street in order to catch a train to Edinburgh for the British and Irish Association of Political Thought conference. Despite BIAPT holding an annual conference since 2008 - and its forerunner the Political Thought Conference dating back to the early 1970s - I am ashamed to say it was the first I have attended. Given how interesting and thought-provoking the papers were, I hope it will not be my last.

Unfortunately the demands of work and home meant that I was only able to attend the first day of this three-day event. I was sorry to miss what looked like some excellent papers on the Thursday and Friday. This means that the comments below focus only on those papers I attended on Wednesday 7th January. The conference was held at the Edinburgh Climate Change Institute and topics such as climate change, environmental political theory and ecology featured prominently in the programme, but my only engagement with that topic came via the first keynote.

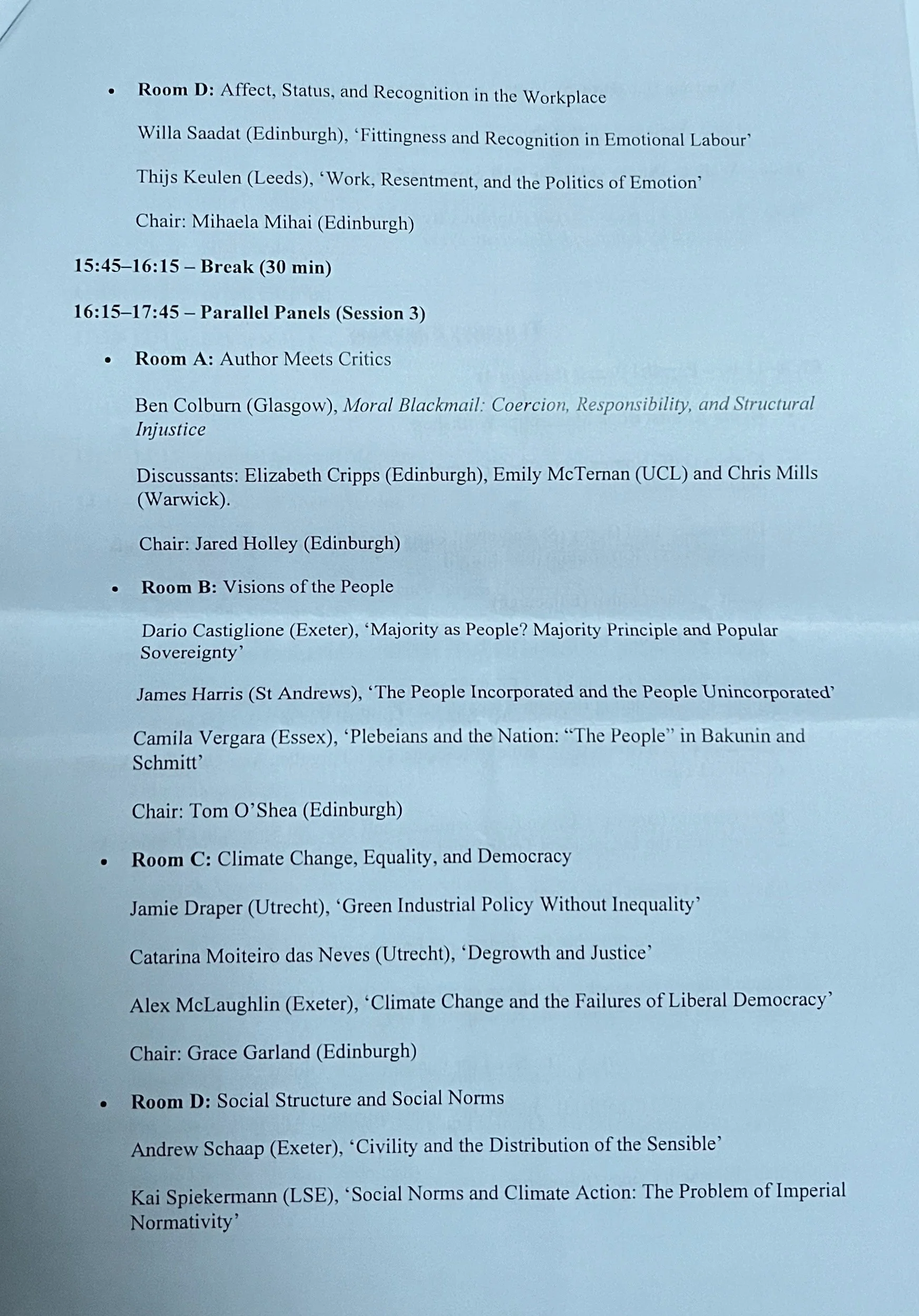

Hugo Grotius, by Willem Jacobsz Delff, after Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt. National Portrait Gallery. NPG 26250. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

One of the recurring themes that spoke to my interests was popular sovereignty. It was explored in detail in the panel entitled 'Visions of the People'. Dario Castiglione explored the majority principle and its relationship to democracy and popular sovereignty. He emphasised the historical importance of majority rule in non-democratic - and even non-political - contexts, noting that many of those discussing the topic today forget this history, tending to see majority rule as specific to democratic government. He explained that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries majority rule was often used for collective decision-making in private contexts, for example in legal or business settings. He also helpfully highlighted some of the issues with majority rule explored by early modern thinkers. These included: the epistemic problem of whether majority rule produces the best result for the community; why and how the majority comes to represent all voters; and on what grounds minorities are obliged to obey the majority. Castiglione noted that in Roman Law the sense that the majority represented the whole group was a legal fiction. For some it can be justified simply on the grounds of numbers or force, but seventeenth-century natural law theorists sought a more robust justification. For Hugo Grotius and John Locke while majority rule was not natural, it was rational. For Locke, it was also moral, since it encompassed both respect for all - in allowing all to contribute to the collective decision - and the opportunity for agency (which the use of sortition would not). By contrast Samuel Pufendorf and Jean-Jacques Rousseau offered a different account, suggesting that majority rule was not rational but rather a matter of convention. Castiglione's argument was that there is a missing element to these discussions, derived from the notion of fraternity or solidarity, which can help to show how and why the minority remains part of the community despite their will not becoming law.

James Harris took as his starting point Philip Pettit's recent book The State, and the argument Pettit develops there about how and why the people as a body can have collective powers (both constitutional and extra-constitutional) against the state. In challenging Thomas Hobbes's view that it is incoherent to imagine the people as a body acting against the state, Pettit distinguishes between three understandings of 'the people': the unincorporated people ('the multiple citizens considered independently of the polity they form' (Philip Pettit, The State. Princeton University Press. 2023, p. 212)); the incorporated people (the people as a corporate body - effectively the state itself); and his own third conception which he calls 'the people incorporating' or the people in a properly political guise - embodying their potential for joint action (Pettit, The State, p. 212). James was unconvinced by this move, but it did generate interesting discussion on the relationship between the people and the state and just how popular sovereignty can be exercised.

The final paper on the panel, by Camila Vergara, approached popular sovereignty and the people from yet another direction, in examining the origins and development of two distinct versions of modern populism. The first, which she traces back to Mikhail Bakunin, reflects plebeian resistance to oligarchic domination. The second, which has its roots in the ideas of Carl Schmitt, is characterised by ethno-nationalism. Whereas for Bakunin, nationality was irrelevant, with the people's interests and their experience of exclusion and oppression transcending national boundaries, Schmitt saw the nation as key, with citizens sharing a common cultural identity. The consequences of these different visions, Camilla argued, are stark, where Bakunin's model is the basis for popular revolution and emancipation through the establishment of bottom-up federative networks, that of Schmitt is used to legitimise state power and disable any exercise of power from below.

Camilla and I had also discussed popular sovereignty on an earlier panel that focused on Arthur Ghins's forthcoming book The People's Two Powers. Here the emphasis was on the relationship between popular sovereignty and public opinion. As Arthur explained, these concepts have conventionally been studied separately but the relationship between them is itself important. Where popular sovereignty is a means by which the people engages in decision-making, generally via voting, public opinion provides an opportunity for the people to express influence via media such as clubs, newspapers and petitions. Arthur's book traces the different understanding of the relationship between these two concepts offered by various thinkers in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century France. He demonstrates that as the century progressed there was a general move towards a position in which popular sovereignty was limited to the election of representatives, with public opinion providing the main opportunity for the people to influence politics between elections. Tracing the relationship between these two concepts across one hundred years of French thought he came to the striking conclusion that while we see public opinion as intrinsically democratic (and as a key component of 'Liberal Democracy') it was originally deployed in the 1790s and early nineteenth century against a version of representative democracy which emphasised popular sovereignty.

This aspect of Arthur's book points towards a second general theme that was explored in a number of the papers I heard - the problem of baked-in principles or assumptions stymying the efficacy of particular concepts. Arthur showed the extent to which modern liberal democracy is inherently anti-plebeian by exploring its origins. Public opinion is emphasised over popular sovereignty and the latter is understood as involving nothing more than the periodic election of representatives. At the same time for many of the thinkers he has studied public opinion was subject to elite control and even manipulation.

The Panel entitled 'Is Civility Reactionary' looked at a different 'baked-in assumption' namely the notion that civility is inherently conservative. As all three speakers noted, the literature on civility and incivility tends to be sharply divided, with formalists praising civility as a social lubricant while critics view civility as an instrument of social control and a means of preventing dissent. All three panellists challenged this view, arguing that there is a role for civility, as Carole Gayet-Viaud put it, as a living part of democratic culture. While the three speakers had the same overall aim and understood the existing literature in similar ways, the research and observations behind each paper were distinct. Gayet-Viaud is motivated by her ethnographic work on urban public life and especially the experiences of women in these settings. Bice Maiguashaca grounded her case in the experience of feminist movements and their use of techniques of solidarity and prefiguration both of which present an alternative to the eruptive and insurrectionary model of incivility emphasised in the literature. Suzanne Whitten's work on Northern Ireland has highlighted to her the importance of civility in building and sustaining a shared life for communities living in post-conflict societies. She explored the idea of plural civilities - of the need for a common set of civility norms in addition to (rather than instead of) the in-group civility norms of different communities, and she explored the ways in which these have to be carefully developed in order to build trust.

In her opening keynote address, Alyssa Battistoni explored another example of baked-in assumptions stymying progress - the commonplace that capitalism, and therefore our current political economy and political theory, are inherently antithetical to environmental perspectives. She began by setting out the view, expressed by many in the field, that climate change presents a challenge to political theory as a discipline; that the terms and categories are not adequate to address the problems it poses and that what is, therefore, required is its fundamental rethinking. While not entirely unsympathetic to this view, Battistoni mounted a strong response to it. She argued that we do not have time for a complete rethinking of political theory, the pressing nature of climate change is simply not compatible with an overhaul of our terms, concepts, and ideologies. Rather we need to do what is possible with what we have to hand. Moreover, she insisted that the history of political thought actually offers rich resources to help us deal with those issues. This is reflected in Battistoni's own recent book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nature, which draws on the history of political economy, and especially Karl Marx's analysis of capitalism, to understand the relationship between nature and the human world. The book offers a diagnosis of why capitalism fails to address ecological matters, because of the capitalist understanding of natural resources as free gifts.

Of course offering diagnoses is one thing, taking action is another. This question of the practical relevance of political thinking was a third theme I identified across the papers I attended. Battistoni addressed this directly, acknowledging that the relationship between understanding and practical transformation is complex. There are limits to what academic political theory can do, and academic research rarely does the work of politics. Moreover, academic work and activism are directed at different audiences and have different underlying aims. Writing a book will achieve some things, she argued, but it does not and cannot achieve others. Nonetheless Battistoni was clear that the two can and do inform each other. This sense of there being a symbiotic relationship between academic work and activism was reflected in several other papers. The papers on civility offered a model in which practice informs thinking (challenging the very notion of civility as inherently reactionary) and the resulting theorising then helps to shape future practice. Similarly Camila Vergara's paper demonstrated how understanding the origins and development of different versions of populism has relevance for how we deal with those movements today. Despite the current state of the world, I left the conference reassured that political theory remains vibrant and convinced that, while it cannot offer simple solutions to today's pressing problems, it can help us to understand them more clearly.