Thomas Hollis has been much on my mind over the past month. April began with a wonderful celebration in Oxford of Blair Worden's 80th birthday year, at which I gave a paper. It was a pleasure and an honour to celebrate this occasion, to meet up with Blair again, and to speak alongside several esteemed colleagues.

Thomas Hollis by Giovanni Battista Cipriani, 1767. National Portrait Gallery, NPG D46107. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

The topic of my paper was the puzzle as to why Hollis was enamoured with Oliver Cromwell; displaying a portrait of the Lord Protector in his house, collecting Cromwell memorabilia, and even cultivating friendships with Cromwell's descendants. This was despite the fact that most eighteenth-century radicals (including those with whom Hollis was closely associated, such as Catharine Macaulay) were hostile to Cromwell, accusing him of having betrayed the parliamentarian cause and of turning it to his own interests.

One of the crucial sources for my paper was Hollis's Diary. My main reason for reading this was to gain a deeper insight into his intellectual pursuits. I am taking careful notes on the books he commissioned for publication and those he sent abroad to various institutions, and I am keen to identify the contacts and networks that facilitated his publishing and dissemination activities. Yet I cannot help being repeatedly distracted by more mundane details. Hollis records when he plays his flute - generally in the evening and often as a means of reducing stress. As a lapsed clarinet player this gives me the urge to get my own instrument out of its case. He also comments on more personal activities: '30 July 1762: Employed the greater part of the morning in washing my feet, & cleansing myself extraordinarily.' (The Diary of Thomas Hollis V from 1759 to 1770, ed. W. H. Bond. Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1996, p. 126). Hollis's recording of his washing routine is striking - not least for how infrequently it takes place. This reminds me that even when we immerse ourselves in the past, important elements - such as the smells - are missing. Hollis is also frequently exercised by his relations (and often disagreements) with his servants. On 8 June 1761 he recorded that his maid servant Mary Foard 'gave me warning to leave me, pretending too much work. Accepted the warning, but differed in opinion with her concerning the work.' (The Diary of Thomas Hollis, p. 75). Two weeks later she left his service voluntarily. This is the stuff of social, rather than intellectual, history, but I have found it helpful in giving me a sense of the man behind the editing and dissemination work, and this enriches my understanding of his intellectual activities.

Image of Bern old town. Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

I myself combined the personal and the intellectual this month in relation to Hollis. At the end of April I went on holiday with my children to Switzerland by train. We visited Geneva, Lausanne, Bern, and Basel. While at Bern I left them to explore the city by themselves while I spent a day at the Universitätsbibliothek to look at its collection of Hollis material.

'Die Hollis-Sammlung' comprises approximately 430 volumes that were sent to the burghers of the city between 1758 and 1765. I am very grateful to Stefan Matter and his colleagues at the library for allowing me to view the collection and to reproduce images from it here. While there was much for Hollis to admire in Bern, his donations to the city owed a lot to Rodolphe Vautravers, whom Hollis had met in Genoa in 1753 and who was a Bernese subject and a member of an important Bernese improvement society. Vautravers' role as intermediary allowed Hollis to make his donations anonymously, describing himself simply as 'An English-man, a lover of liberty, his country, and its excellent constitution'. Vautravers was also involved in presenting the collection to the Bernese Assembly and persuading them to accept the donation.

Bern, UB Münstergasse, MUE Hollis 183. Image, Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

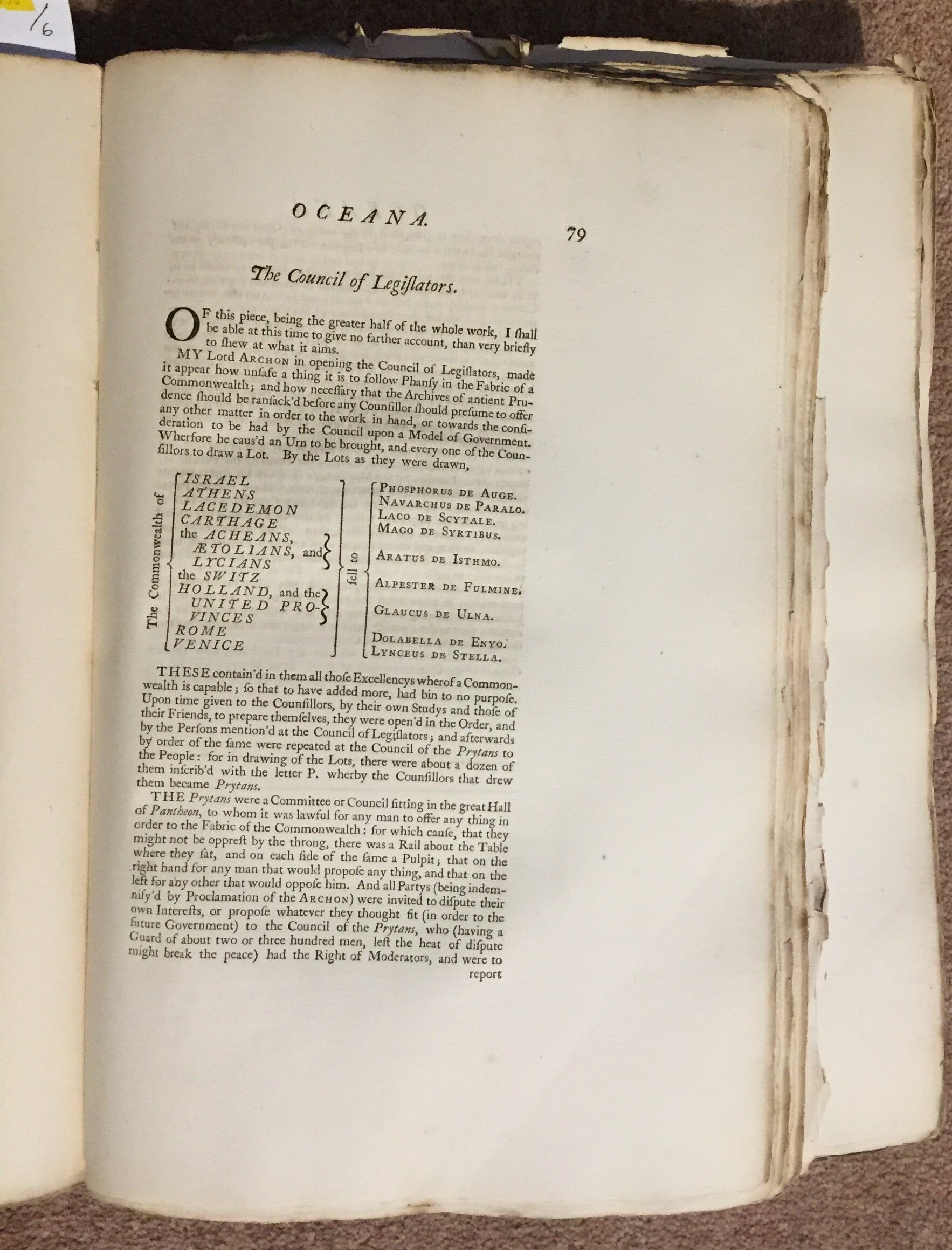

I will be exploring what I found in the collection in future papers and publications. Here I want to reflect on just one volume: Hollis 183. The binding of this volume is not as lavish as some, but there is gold tooling on the spine and significant marginalia within. The volume is a Sammelband comprised of Robert Molesworth's major works (An Account of Denmark, An Account of Sweden and the 1721 edition of his translation of François Hotman's Franco-Gallia) alongside more minor works by him and others. I will focus here on the major Molesworth works, which we know from other copies were of particular significance to Hollis. A marginal note on the flyleaf of the edition of An Account of Denmark sent to Harvard University describes that work and Molesworth's 1721 preface to Hotman's Franco-Gallia as 'two of the noblest in the English Language' (W. B. Bond, "From the Great Desire of Promoting Learning": Thomas Hollis's Gifts to the Harvard College Library, Cambridge - Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2010, p. 136). Hollis reinforced that point in the Bern volume by writing 'Ut Spargum' ('that we may scatter them') on the title pages of both works. As I have noted before, Hollis added this phrase to many of the works he sent to specific institutions to indicate their importance

Bern, UB Münstergasse, MUE Hollis 183. Image: Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

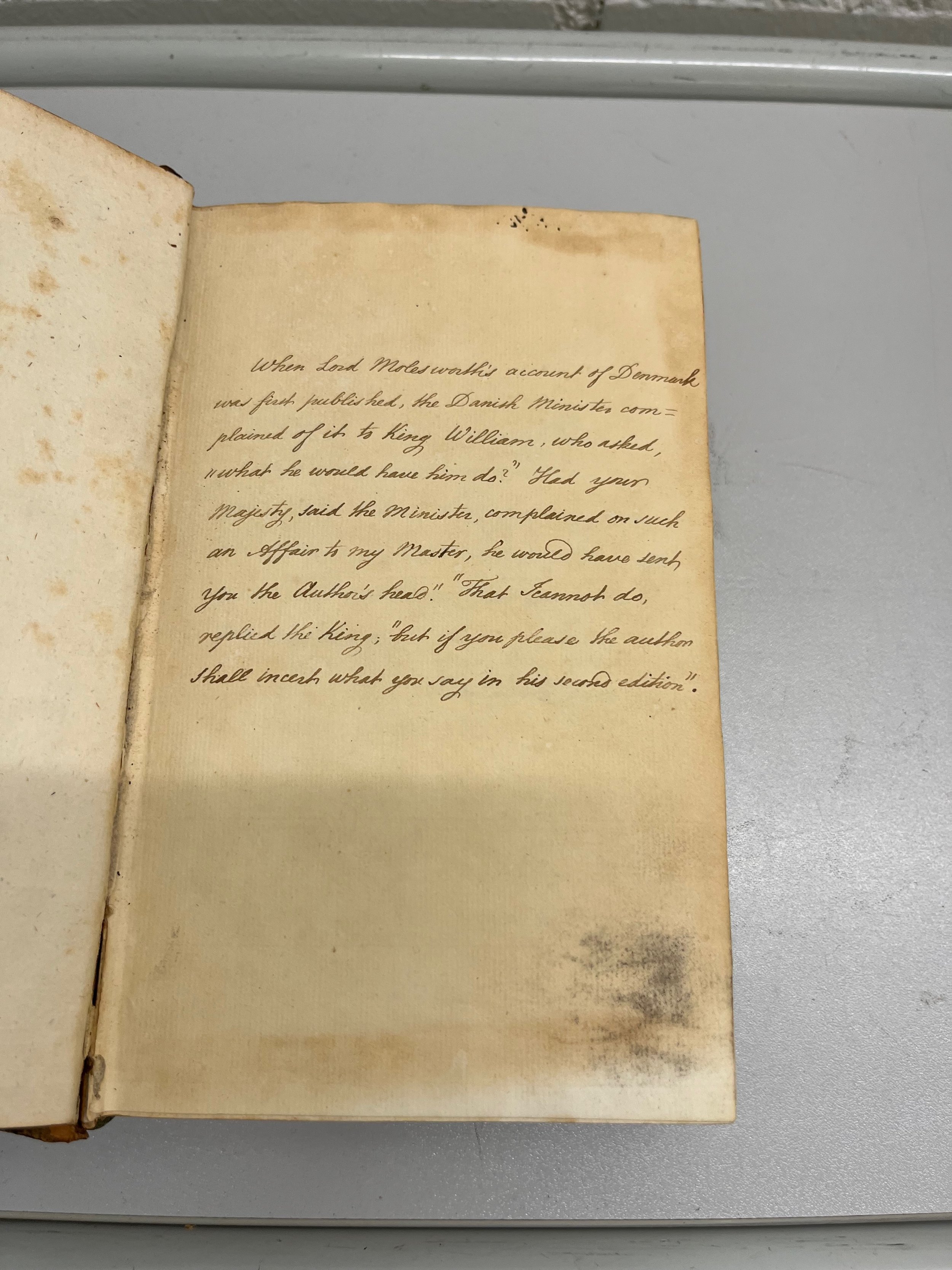

The other marginalia in the volume is more distinctive. On a flyleaf, Hollis added a handwritten account of an exchange that took place immediately following the publication of An Account of Denmark between the Danish Minister (presumably the Danish Ambassador to England) and King William III. The comment reinforced the claim about the contrast between English liberty and continental absolutism that was made in the volume itself. The Danish Minister apparently complained to King William about the book and the King asked in reply what the Minister would have him do. The Minister responded that if the roles had been reversed, the Danish King 'would have sent you the Author's head'. King William replied: 'That I cannot do ... but if you please the author shall insert what you say in his second edition.' On the next page Hollis had copied out a sentence 'From an old tract', - namely Marchamont Nedham's The Excellencie of a Free State:

Bern, UB Münstergasse, MUE Hollis 183 : 2. Image: Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

The truth is of it is, the Interest of

freedom is a Virgin, that every one

seeks to deflower; and like a Virgin it

must be kept from any other form, or

else, so great is the Lust of mankind

after dominion, there follows a Rape

upon the first opportunity.

The emphasis on the value and nature of freedom continues in the marginalia added to the title page of An Account of Sweden.

No free People ever yet existed, that left its fate to the conscience of a ruler; and with us it is a maxim, that the Kingdom shall be ruled, "not by the King's conscience, but by the known Laws".

From the journal of the Senate of Sweden of Nov. 7. 1755.

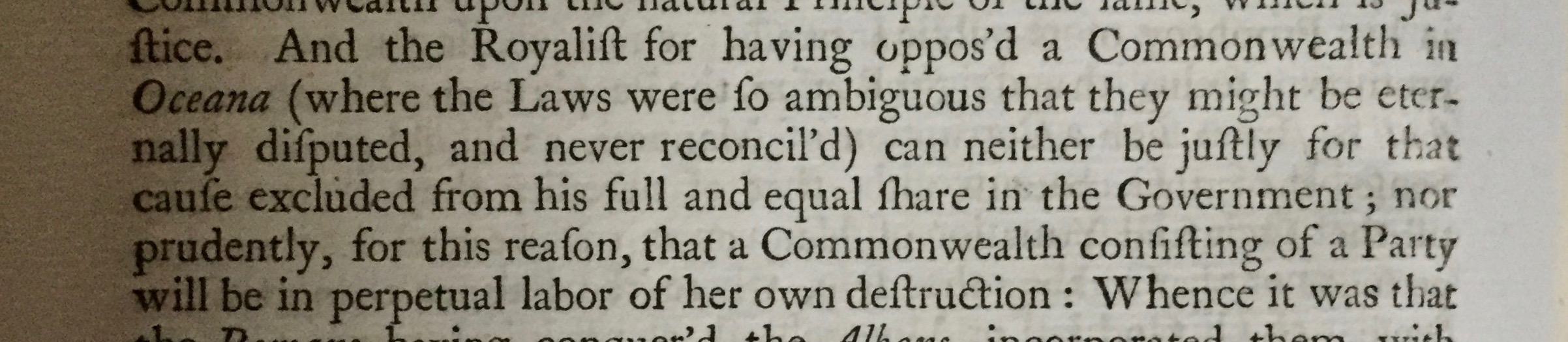

This is, of course, an assertion of the notion of liberty as independence, which was examined in detail by Quentin Skinner in his latest book and discussed in my last blogpost.

Bern, UB Münstergasse, MUE Hollis 183 : 5, p. vii. Image: Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

Hollis also annotated the prefatory material to the 1721 edition of Franco-Gallia. It was there that Molesworth had set out his political creed - which he described as being that of a 'real Whig'. In the version he sent to Harvard, Hollis added a comment to indicate that he shared Molesworth's political creed. (Bond, "From the Great Desire of Promoting Learning", p. 107). Similarly, in the Bern volume he underlined this section and added a note at the bottom: 'Observe this Political faith, how fine!' He also provided further reading for his audience. On page xxv, where Molesworth declared that 'A Whig is against the raising or keeping up a Standing Army in Time of Peace', Hollis underlined the passage and added a note referring his readers to works against a standing army by John Trenchard, Thomas Gordon and Walter Moyle. Hollis perhaps thought this discussion was particularly relevant given the Swiss attitude to defence. Bern, like other Swiss cantons, was protected by a militia of freeholders. A few pages later, again on the subject of defence, Hollis referred readers to specific pages from Bernard Mandeville's The Fable of the Bees. All of these works were among those sent to Bern, meaning that readers of this marginalia would have been able to follow up his references

Bern, UB Münstergasse, MUE Hollis 183 : 5, p. xxv. Image: Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

Hollis's marginalia demonstrate his deep regard for Molesworth and his ideas, as well as his belief that they were relevant to the citizens of Bern in the mid-eighteenth century. There is, of course, a parallel here with Molesworth's own treatment of Hotman's work. It had originally been published in 1573, but Molesworth believed it still had resonance in the early eighteenth century. His 1721 translator's preface was designed to show why.

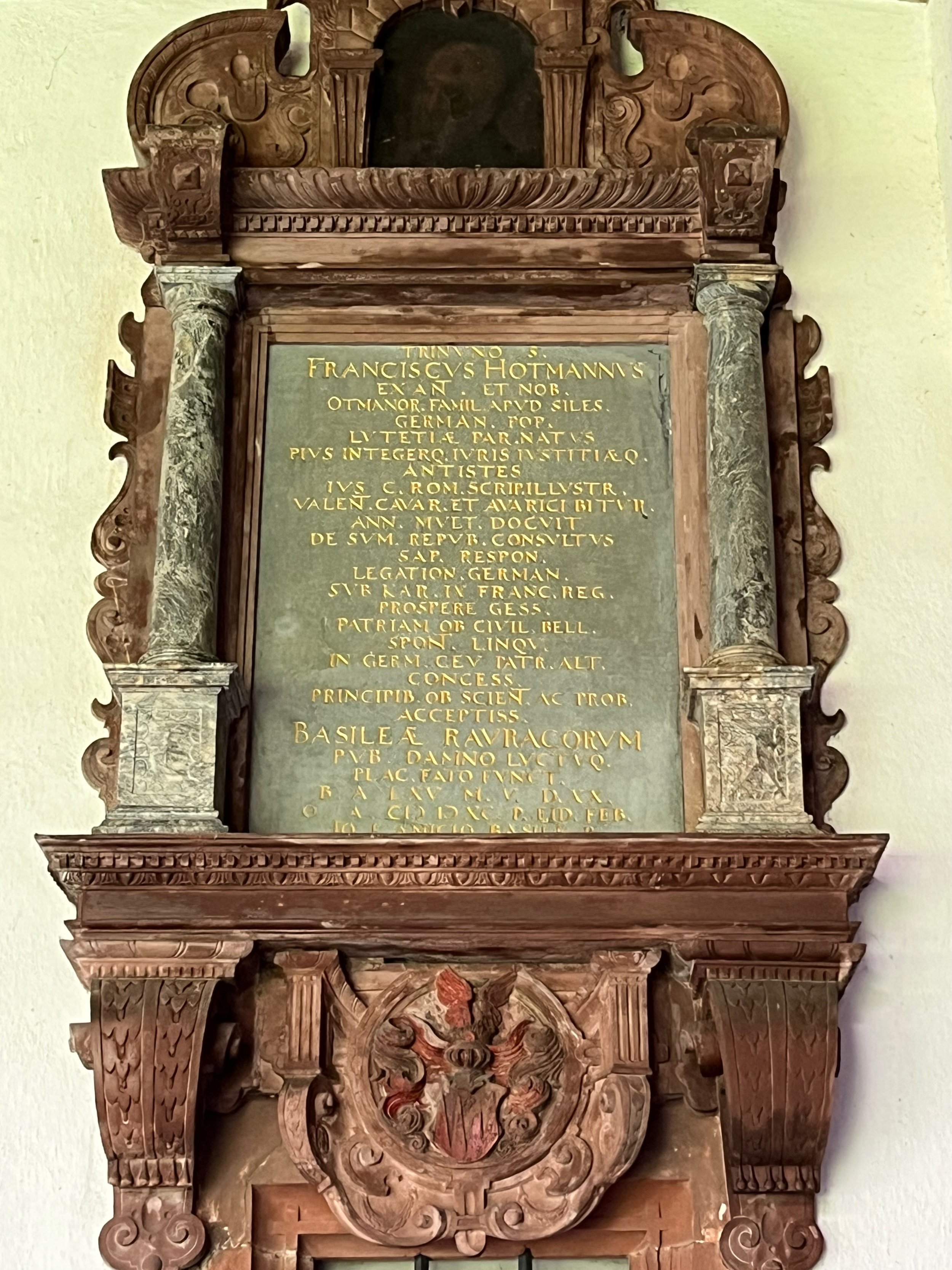

Our homeward journey involved taking a train from Bern to Basel where we could then pick up the TGV back to Paris - and then via Eurostar home. Keen to make the most of our trip we travelled to Basel a few hours early and briefly explored the city. We came to the Münster and saw an open door into the outer crypt. Curious, we entered and began looking at the funeral monuments - many of which dated from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Struggling to decipher the Latin I turned and spotted a name I recognised: François Hotman. A quick check on the internet confirmed that the author of Franco-Gallia died in Basel in 1590. As I stood looking at his funeral monument I thought of Molesworth and Hollis and wondered whether, on his own trip to Switzerland in 1748, Hollis had visited this monument himself.

François Hotman’s memorial in the outer crypt at Basel Münster. Image, Rachel Hammersley, 2025. I am very grateful to my friend and colleague Katie East for assisting me with the Latin.