Statue of Jean-Jacques Rousseau in Geneva. Image by Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

On a trip to Switzerland earlier this year I looked forward to visiting the statue of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the museum dedicated to him in Geneva. What I did not expect to find were references to Rousseau in the Hollis collection at the Universitätsbibliothek in Bern. Yet the material there alerted me to the fact that Thomas Hollis communicated with the notoriously prickly Genevan thinker and defended his cause in 1765. Moreover, the case had profound consequences for Hollis's book dissemination project.

Rousseau published both Du Contrat Social and Emile in May 1762. Both were condemned by the authorities in Catholic France and in Rousseau's Calvinist home town of Geneva. The French ordered Rousseau's arrest causing him to flee from Montmorency (just north of Paris), where he had been living, to Neuchâtel, which was then governed by Prussia. Rousseau renounced his Genevan citizenship and began work on his Confessions. In 1765 he spent the summer on the island of Saint Pierre in Lac de Bienne, which was under the authority of Bern. Rousseau had visited the island a year earlier and had cultivated a desire to live there. He settled on a 'wild and uncultivated island' to the south of the main island and apparently 'detached from it by storms'. Rousseau's description of it in The Confessions conveys his love for it:

its gravelly soil produces nothing but willows and persicaria, but there is in it a high hill well covered with greensward and very pleasant. The form of the lake is an almost regular oval. The banks, less rich than those of the lake of Geneva and Neuchatel, form a beautiful decoration, especially towards the western part, which is well peopled, and edged with vineyards at the foot of a chain of mountains (Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Confessions. London, 1903. Project Gutenberg. Book XII).

Isle de Saint Pierre in Lake Biel. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Rousseau claimed that he intended to spend the rest of his life on the island, but his happy stay was cut short after just six weeks when the freemen of Bern ordered his expulsion from their territory. He travelled from Bienne to Strasbourg and from there to Paris arriving in the French capital on 16th December 1765.

‘Jean-Jacques Rousseau’, by Angelique Allais. National Portrait Gallery. NPG D19002. Reproduced under a Creative Commons licence.

News of Rousseau's fate spread across Europe. At the end of October Rudolph Vautravers wrote to his friend Hollis in London reporting that the local 'Bigots' had obtained an order from the magistrates at Berne 'to expel poor Rousseau ... from his beautiful Retreat ... in the Lake of Bienne (where he had just settled himself; as he hoped, out of the Reach of his enemies'. Rousseau, Vautravers reported, had moved to the city of Bienne itself and if necessary would escape to Potsdam 'under the immediate Protection of a wise and beneficent Monarch, who hath been pleased constantly and pressingly to offer it to him'. (Vautravers to Hollis, 28 October 1765). Less than two weeks later Vautravers wrote again to announce that 'poor Rousseau has been expelled from all Switzerland' and was heading for Potsdam, though given his poor health it was uncertain whether he would survive the journey (Vautravers to Hollis, 9 November 1765).

Hollis had known Vautravers since 1759. In November of that year he recorded in his diary that he had taken tea with Vautravers (who was then staying in London) for the first time. Hollis's interest in Switzerland - and in particular in the Canton of Bern - also dated back to that time. He had been preparing a parcel of books for the Library at Bern since April and it was finally sent with Vautravers' assistance in January 1760. Two years later Vautravers settled at Rockhall near Bern.

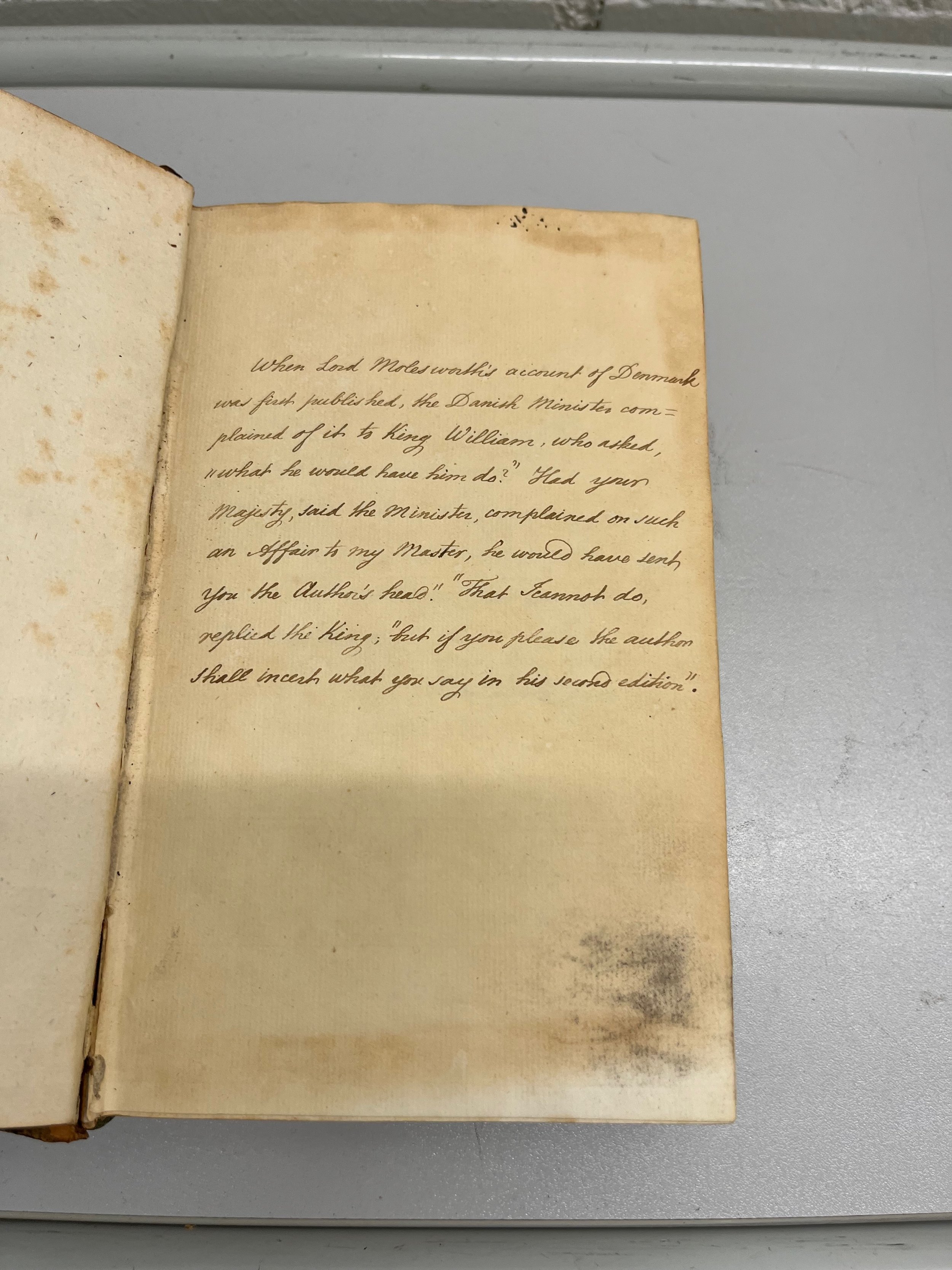

Vautravers was still living at Rockall when the controversy over Rousseau erupted and hence his letter to Hollis. In response, Hollis sent Vautravers a package for Rousseau which contained an invitation for him to come to England and a copy of John Wallis's grammar (to help him to improve his English language skills). Unfortunately, the package did not reach Rousseau before he left the country. Rousseau did travel to England in 1766, but on the invitation of David Hume rather than Hollis. Yet Hollis did take some action on Rousseau's behalf in London. On 18th November 1765 he went to see Noah Thomas, the director of the St. James' Chronicle, to present him with an extract from Vautravers's letter requesting that it be printed in the paper. It duly appeared the following day. Vautravers's letter announcing Rousseau's expulsion from Switzerland followed on 28th November. The publication of these letters, Hollis hoped, would secure the support of the English public for the exiled Genevan author while also highlighting the precariousness of civil and religious liberty. The following year, Hollis received from Vautravers several sketches depicting Rousseau's 'sufferings' in Switzerland by the artist Samuel Jerom Grim. These he passed on to his close friend Thomas Brand.

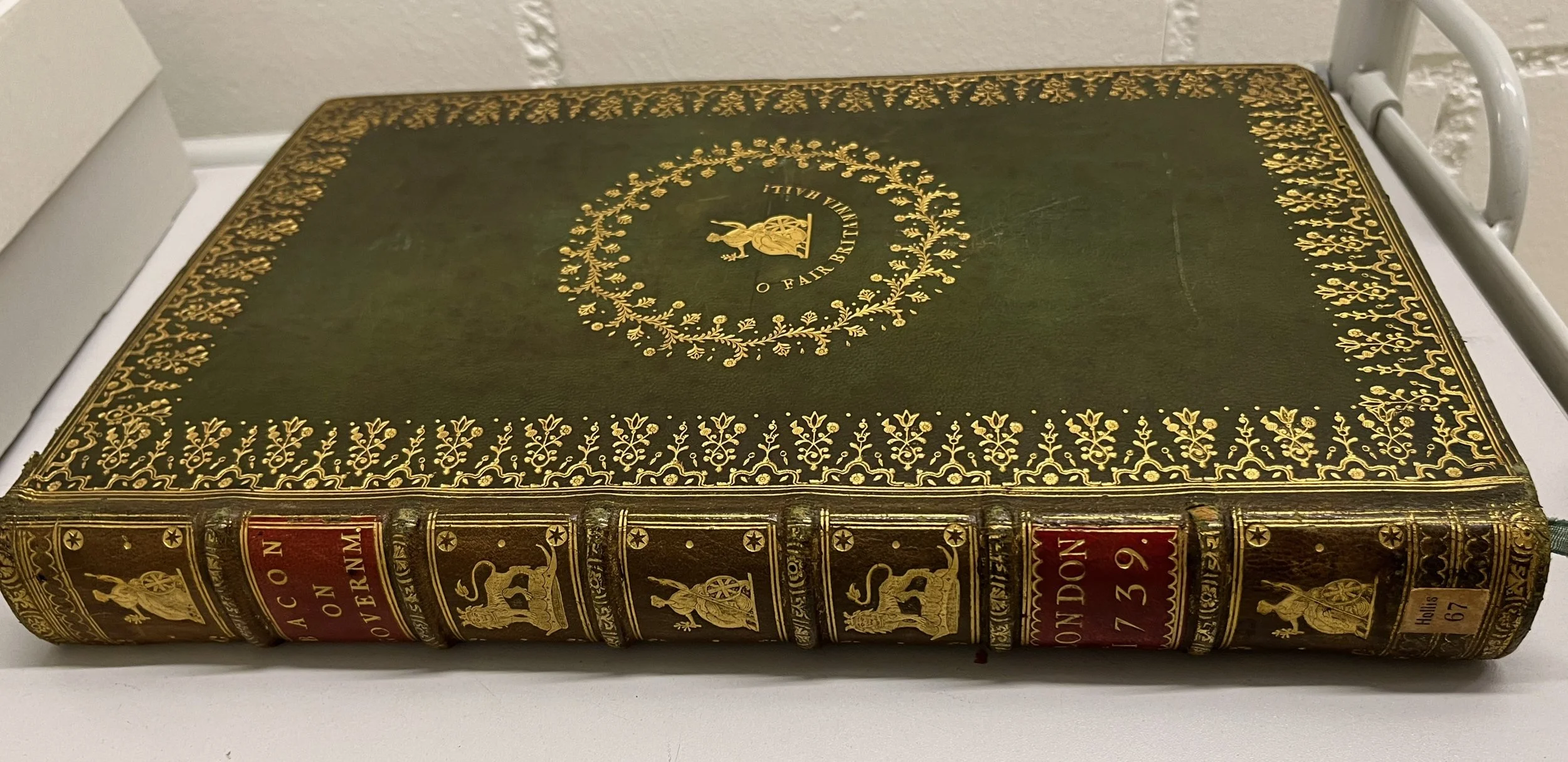

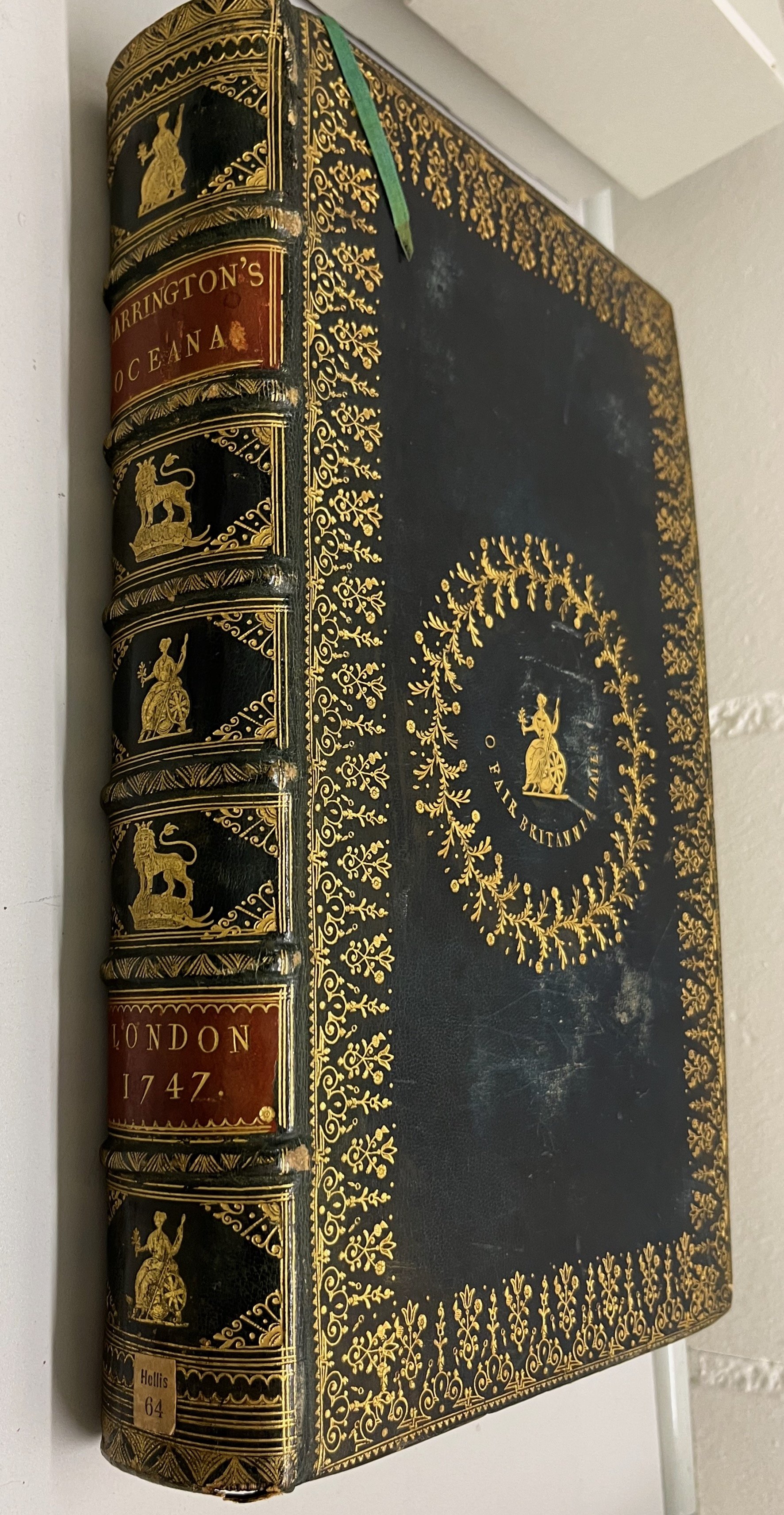

One of the beautifully bound books that Thomas Hollis sent to the Library at Bern. Bern, UB Münstergasse, MUE Hollis 67. Image Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

The treatment of Rousseau on the part of the Bern authorities had a huge impact on Hollis. His initial sympathy for the Canton owed much to their protection of the English republican exile Edmund Ludlow in the late seventeenth century. Their less sympathetic treatment of Rousseau one hundred years later soured Hollis's favour. Though he sent the Library more than 200 volumes between 1759 and 1765 - including some that were presented in extremely lavish bindings - he sent nothing after 1765. The treatment of Rousseau by the Bernese authorities indicated that they were not committed to the principles of civil and religious liberty that Hollis held so dear and were not, therefore, worthy recipients of his gifts.