In early December the justice secretary, David Lammy, announced that in order to address the huge backlog in the criminal justice system, jury trials should only be used in the most serious cases in England and Wales. Though he subsequently back-tracked a little on the original proposal, the plan remains to significantly reduce the use of trial by jury in minor cases. Lammy's announcement prompted some commentators to note that trial by jury has been an important part of our legal system since Magna Carta. It led me to reflect on those political activists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries who both celebrated the idea of trial by jury in theory, and relied on it in practice when they found themselves on the wrong side of the law.

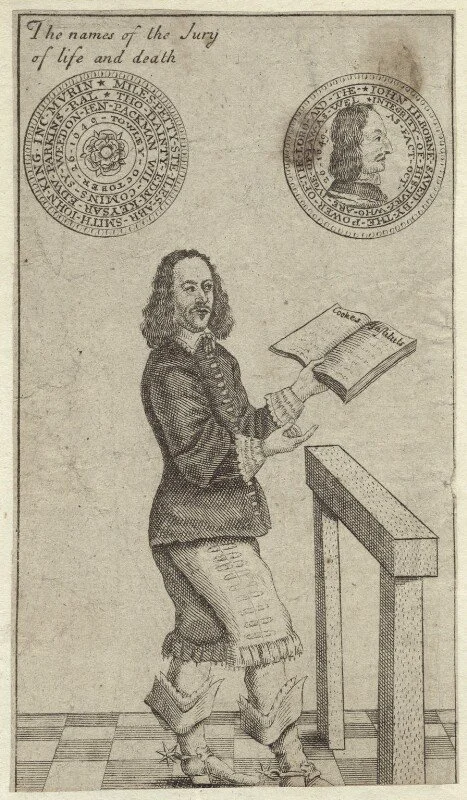

John Lilburne, unknown artist. National Portrait Gallery. NPG D28982. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

This famous image of the Leveller John Lilburne depicts him defending himself at the bar, alongside a medal that was designed to commemorate his acquittal by a jury in October 1649. Lilburne had been charged according to an act which declared it treason to claim either in writing or verbally that the Commonwealth Government (established after the execution of Charles I) was 'tyrannical, usurped, or unlawful'. While Lilburne was no fan of the monarchy he had distanced himself from the regicide and was highly critical of the Rump Parliament, insisting that it was illegitimate.

Lilburne was tried in front of a jury at the Guildhall in London in the autumn of 1649. He chose to defend himself and is depicted here with a copy of Sir Edward Coke's Institutes in his hand. He used Coke to argue that the English understanding of fundamental liberty (reflected in both Magna Carta and the 1628 Petition of Right) insisted that an Act of Parliament should be deemed invalid if it overrode principles of equity and morality or of common law. Of course, Coke also presented trial by jury as a fundamental English right and as crucial to the liberty that was understood to be enshrined in the English constitution. Lilburne spoke at length during the trial and at the end he gave a long speech directed at the jury in which he presented himself as a 'freeborn Englishman and a Christian' who was fighting for the rights of all 'freeborn Englishmen'. The speech was clearly rousing - at its end many of those present responded 'Amen' and the jury took just an hour to deliver its verdict 'Not Guilty', prompting onlookers to cheer and shout in celebration for more than half an hour (Andrew Sharp, 'Lilburne, John (1615?-1657)' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://doi-org.libproxy.ncl.ac.uk/10.1093/ref:odnb/16654). Lilburne and his supporters were convinced that being tried by a jury had been crucial to the outcome. The commemorative medal lists the names of the jurors and declares:

John Lilborne saved by the power of the Lord and the integrity of his jury who are

juge of law as wel as fact October 26 1649.

Lilburne and his supporters were adamant that trial by jury offered an important check on the government, ensuring that it could not simply silence opponents - or those who asked awkward questions - with impunity.

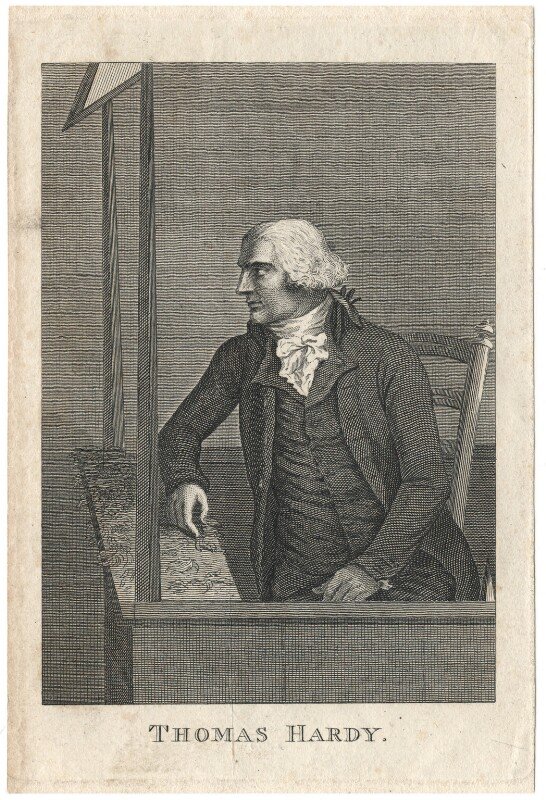

Thomas Hardy, unknown artist. National Portrait Gallery. NPG D3227. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

Jury trials were still serving this function over one hundred years later during another period of intense political crisis. On 12th May 1794 the president of the London Corresponding Society (LCS), Thomas Hardy, was arrested on a charge of high treason. In the days that followed eleven other reformers, most of whom were members of either the LCS or the Society for Constitutional Information, were also arrested. Among their number was Thomas Spence. Their 'crime' was continuing to campaign for parliamentary reform at a time when Britain was at war with the revolutionary regime in France. The King sent a message to the House of Commons expressing his concern at the supposedly 'seditious practices' of corresponding societies. Only three leading figures (Hardy, John Thelwall and John Horne Tooke) were brought to trial. Tried by juries, in late October, all three were acquitted and following this the other LCS prisoners - including Spence - were also released.

Token commemorating the release from prison of Thomas Hardy in 1794. Unknown artist. National Portrait Gallery. NPG D7039. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

In the light of these acquittals, and against the background of the ongoing French Revolution and war with France, the authorities sought to further limit the actions of reformers. The 'Treason Act 1795' redefined treason to encompass simply 'imagining the King's death' through writing or speaking (36 Geo 3 c.7). While the 'Seditious Assemblies Act' made gatherings of 50 people or more illegal (36 Geo 3 c. 8). In addition the authorities seem to have got better at manipulating the jury system so as to avoid acquittals and ensure that verdicts went in their favour.

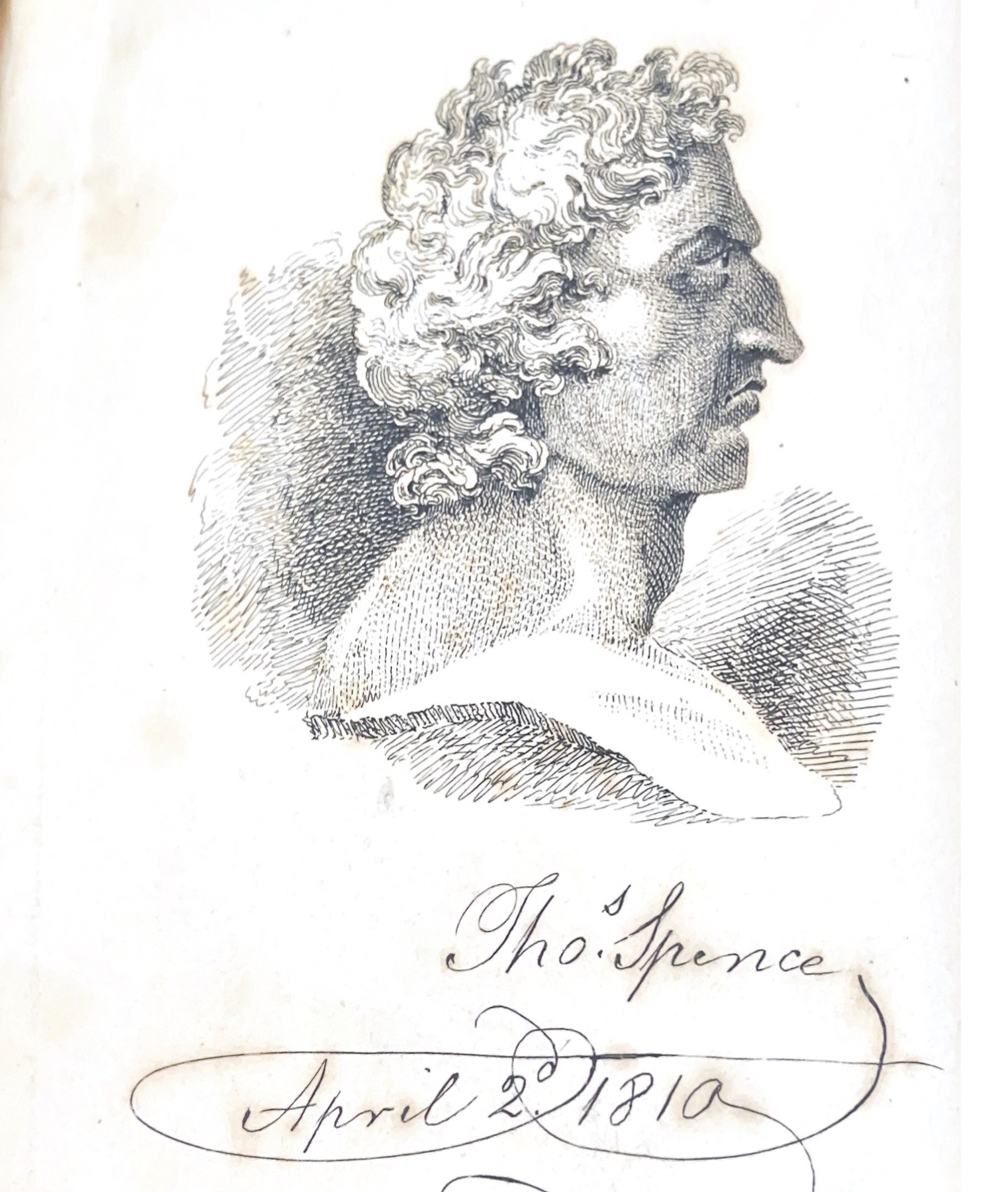

Having been released in 1794, Thomas Spence fell foul of these changes, being arrested again in 1801, this time for having 'composed and published a seditious libel' in the form of his pamphlet The Restorer of Society to its Natural State (The Important Trial of Thomas Spence. London, 1803). Spence defended himself but was immediately found guilty by the jury. He was subsequently brought before four judges who sentenced him to a year's imprisonment in Shrewsbury jail and a fine of £20.

Thomas Spence, from an image held among the Hedley Papers at the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society. Reproduced with kind permission.

In his account of his trial, Spence complained of the unfairness and corruption of the legal system. He claimed that the Attorney General and journalists had misconstrued and misrepresented his ideas, saying that he was 'held up to the public as a fool or a madman' and was accused of seeking to overthrow all private property, whereas it was only landed property that he argued should be owned and maintained by local parishes. He also argued that, given the nature of the jury, the odds were stacked against him. It was unfair, he asserted, that he was being tried by men of property when his system explicitly called for a modification of landed property, which meant that his jurors had an interest in the outcome of his trial. It would have been fairer, he insisted, if at least half of the jury had been labourers without a vested interest (or at least with the opposite interest).

Like Lilburne, Spence went on to present himself as speaking not just on his own behalf but on behalf of the whole human race - especially the 'no-hopers'. The consequence of the verdict against him, he suggested, was that nobody should put forward any proposals for the public good, and in particular that labourers had no right to propose new laws. Laws it seemed were made by and for men of property. Rather than prosecuting people for proposing plans to improve human happiness, Spence argued, society ought to be prosecuting those who hold back such reforms despite their utility.

Of course, Lilburne and Spence were distinctive in being prosecuted for challenging the established regime, but that is also true of some who find themselves in the criminal justice system today. Will it be those people, I wonder, who will lose their right to trial by jury under the government's new proposals?