Last month's blogpost focused on the dissemination of political texts - in various forms - by two seemingly very different eighteenth-century figures - Thomas Hollis and Thomas Spence. This month's post will show that the parallel between these two men ran even deeper. They both recognised that if the texts they disseminated were to have an impact, attention had to be paid to the linguistic skills of their audience - in particular the capacity to read proficiently and to speak and debate effectively.

John Wallis by David Loggan, 1678. National Portrait Gallery: NPG 639. Reproduced under a creative commons licence.

In late June 1760, Hollis first broached the idea with the printer and bookseller Andrew Millar of reprinting John Wallis's Grammatica linguae anglicane (1653), which offered an introduction to English grammar for those with knowledge of Latin. Hollis linked this proposal directly to his wider political project. The volume would be 'for the benefit of Foreigners, and the spreading of the principles of truth and Liberty'. (The Diary of Thomas Hollis, ed. W. H. Bond. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1996. p. 36. 28 June 1760). As discussed in last month's blogpost, Hollis sent various English political texts abroad with the aim of advancing liberty. If the recipients were to make good use of them, they would need an understanding of the English language. Hollis emphasised this point in a handwritten inscription that he added to the copy of another work, the Bibliotheca Literaria, which he sent to Harvard College in 1767. Having sent books on government, he explained, he then sent: 'Grammars, Dictionaries of Root and other Languages, with critical Authors; in hope of forming first rate Scholars, the NOBLEST of all Men!' (William H. Bond, "From the Great Desire of Promoting Learning": Thomas Hollis's Gifts to the Harvard College Library. Cambridge: Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2010, p. 34). He also drew up a list of 'books favourable to Liberty, and ingenuous actions' to be placed at the end of the Wallis edition to further cement the connection between language and politics. (The Diary of Thomas Hollis, p. 220. 24 November 1764). Having commissioned the edition of Wallis's work, Hollis then distributed copies of it very widely, including sending a copy with the donations of political books that he sent to key institutions abroad. The larger donations that he made to Harvard and Bern also included other linguistic works such as John Wilkins, An essay towards a real character and a philosophical language (1668) and Robert Bellers, The Plan of a Dictionary of the English Language (1747).

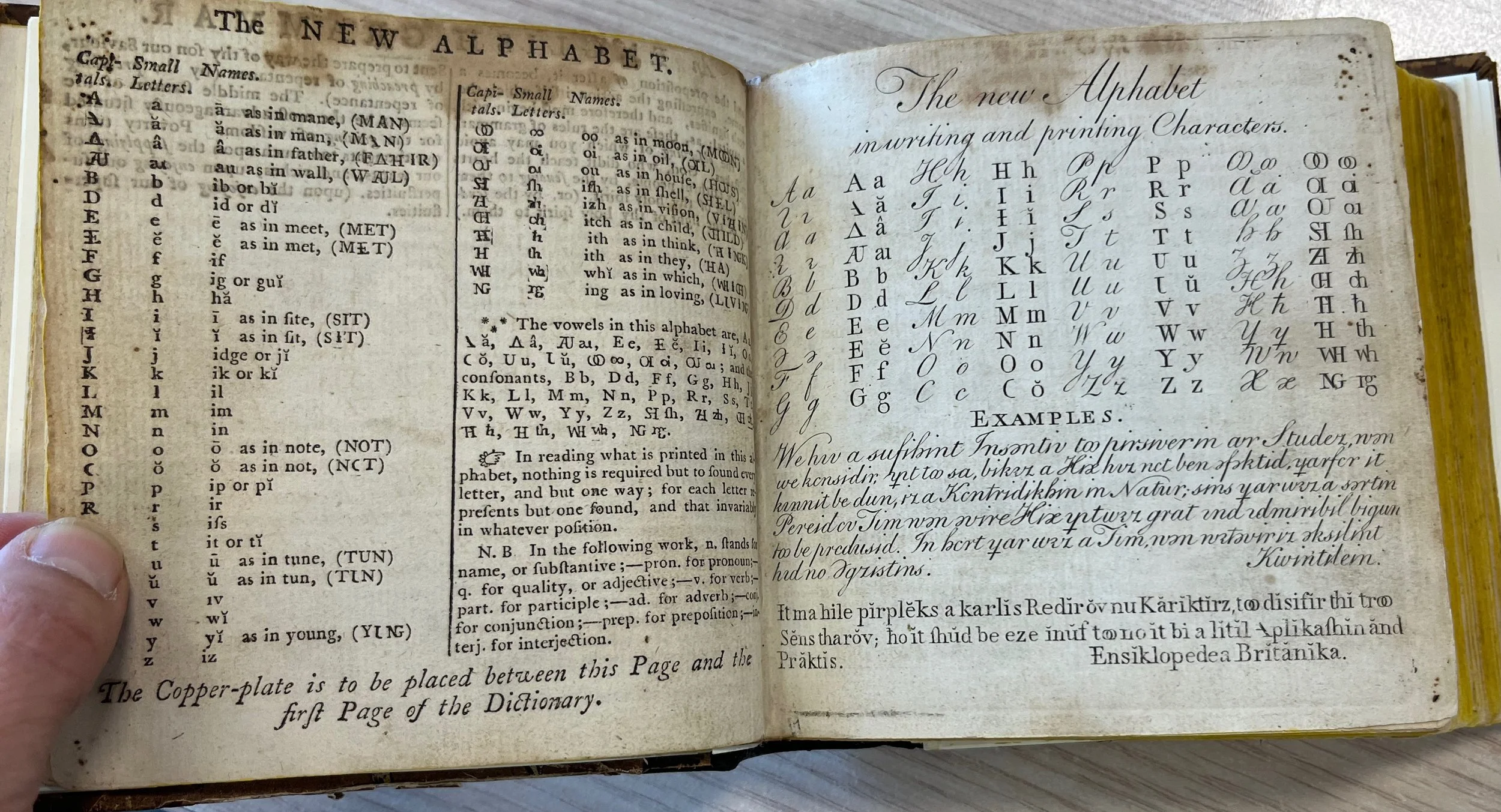

Thomas Spence, The Grand Repository of the English Language (Newcastle, 1775) in which he set out his phonetic alphabet. Image by Rachel Hammersley from the copy held at Newcastle City Library. Reproduced with kind permission.

Spence, too, recognised the connection between language skills and political understanding. In the 1770s he designed a phonetic alphabet which he continued to promote even after his move to London - printing several of his own works in this distinctive format. Whereas Hollis's priority was providing linguistic texts so that foreigners could benefit from works printed in English, Spence's main concern was the labouring classes in England 'who generally cannot afford much time or expence in the educating of their children, and yet they would like to have them taught the necessary and useful art of reading and writing' (Thomas Spence, The Grand Repository of the English Language. Newcastle upon Tyne, 1775, Preface). For Spence, as for Hollis, the ultimate goal was the promotion of liberties and rights. Spence was explicit that his phonetic alphabet would allow 'the very poorest' to acquire 'such Notions of Justice, and Equity, and the Rights of Mankind, as rendered unsupportable every Species of Oppression' (Thomas Spence, The Real Reading-Made-Easy. Newcastle, 1782, pp. 41-2).

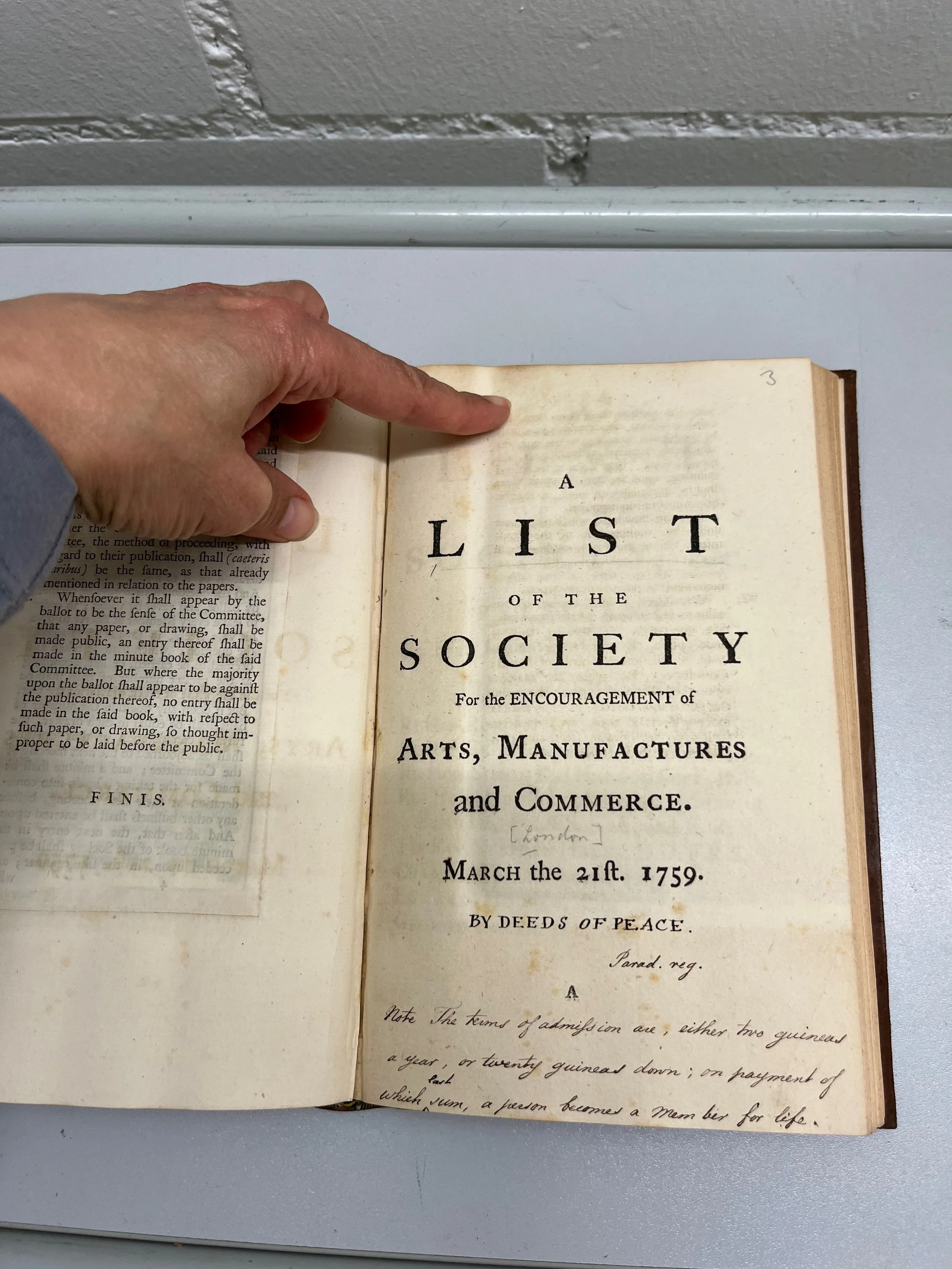

Bern, Universität Bibliothek, ‘Die Hollis-Sammlung 79(3) A List of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (London, 1759). Reproduced with kind permission. Image, Rachel Hammersley, 2025.

While both men clearly placed great emphasis on the written word, they also saw the benefits to be gained from people gathering together in societies to discuss ideas. Hollis was a committed member of several London-based societies, and he enthusiastically promoted them elsewhere. His decision to send books to the public library at Bern in Switzerland was partly motivated by the establishment there in 1759 of 'Die Oekonomische Gesellschaft' (The Economic Society) which was aimed at bringing about improvements to the canton and operating as a channel for the reception of new ideas from abroad. Hollis wrote to his local contact, Rodolphe Vautravers, the following year noting his delight that the society was flourishing (A. Thirouard Wyss, The Hollis Collection in Berne, p. 24). Among the parcels of books Hollis sent to Bern he included not only works on agriculture and husbandry, that spoke to the aims of the Bern society, but also works on societies themselves including Histoire de l'academie Royale des sciences, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Thomas Birch's The History of the Royal Society and A copy of the royal character and statutes of the Society of Antiquaries of London. In 1765 members of the societies at Bern and Biel sent Hollis a report of their activities as thanks for his support. Rather than keeping the report, he sent it on to the American colonies in the hope of encouraging the establishment of similar societies there.

The only known surviving copy of Spence’s original lecture at the Newcastle Philosophical Society in 1775. From the Anthony Hedley Papers at the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society. Reproduced with permission.

Spence too both participated in and organised gatherings to discuss ideas from an early age. Moreover he continued to do so even after his less than positive early experiences. Spence was expelled from the Newcastle Philosophical Society in November 1775 having delivered a lecture entitled 'Property in Land Every One's Right', which he then had printed for circulation. Around the same time, he formed a debating society of his own, which met at the school he taught at on Broad Garth, Newcastle. One evening they debated his ideas about property in land but the other young men at the society - including Spence's friend Thomas Bewick - were not convinced, and the debate went against Spence. Afterwards Spence accused Bewick of betraying him and challenged him to a fight. After moving to London, Spence joined the London Corresponding Society (LCS). In the spring of 1793 his shop was named as a venue where an LCS petition in support of parliamentary reform could be signed (Mary Thale, Selections from the Papers of the London Corresponding Society, 1792-1799. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983, pp. 57 and 60-61.) Again, his involvement in the Society got Spence into trouble; he was arrested alongside other members of the LCS on 20 May 1794 and was imprisoned until December. Yet Spence remained undeterred. In March 1801 a meeting was held at which 'Citizen Spence's theory of Society' was endorsed, and it was resolved that supporters of the system would meet in small numbers 'after a free and easy manner' to discuss those ideas (British Library: Add. MS. 27 808, 201 and 203). An advert in a collection of Spence's songs also promoted Spence's ‘free and easy’ gatherings, which were held at the Fleece on Little Windmill Street on a Monday or Tuesday evening at 8pm

Both Hollis and Spence, then, seem to have been committed not just to spreading political ideas in print, but also to facilitating the exchange and discussion of ideas in person in dedicated societies. This meant that they were concerned not only with the development of reading and writing skills, but also with those associated with speaking and listening.

It would be easy to downplay these aspects of their projects - and even to dismiss them as further evidence of the eccentricities of these two men. Yet their concern with language skills - and their sense that improving those skills was crucial to the preservation of liberty and challenging inequalities - speaks to current concerns and connects to another of my activities.

In 2018 an All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Oracy was established in Parliament, with the aim of 'helping every child [to] be a confident communicator and find their voice' (https://www.marjon.ac.uk/research/knowledge-exchange/Oracy_APPG_InterimReport_Dec20.pdf) The APPG defined Oracy as: 'the ability to speak eloquently, to articulate ideas and thoughts, to influence through talking, to collaborate with peers and to express views confidently and appropriately'. It also recognised the importance of Oracy for improving attainment in schools, preparing students for future study and careers, and for citizenship and empowerment. Finally, the group noted marked differences in Oracy skills arising from social background, and observed that the language gap had widened as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

These findings chime with my own experience as a university lecturer. While the university students are some of the brightest, there is generally still a marked difference in Oracy skills depending on education and social background. Seminar teaching is a crucial component of university education - especially in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Successful seminars require students to express their own opinions and interpretations of the material they have read. They need to be able to speak fluently, to listen carefully, and to debate sensitively and constructively. Yet, over the years, students have seemed less and less willing to participate in seminars. Some simply do not turn up at all, and others attend but do not contribute to the discussion. Recent focus-groups conducted as part of an Oracy project at Newcastle University found that, while the majority of the students questioned were confident when sharing their ideas in small groups with people they already know well, they were much less confident when speaking in front of the whole class - or even in small groups with people they did not already know. Those of us involved in the project (which includes academics from several different disciplines, school teachers and the educational outreach team from the University Library with support from the charity Voice 21) will be testing strategies for improving the Oracy skills of our students and sharing our findings with each other. I would like to think that Hollis and Spence would approve.