Various things I have read and observed this month have led me to think again about democracy and attitudes towards the poor, both in the past and today. In this month's blogpost I share some of these reflections.

One task I have completed this month is to write a review for the journal History of Political Thought of the excellent monograph Anti-Democracy in England 1570-1642 written by Cesare Cuttica. Though the book's main focus is the arguments put forward by opponents of democracy, Cuttica convincingly challenges the still persistent view that representative democracy was an invention of the age of Revolution in the late eighteenth century. There are some good reasons for this view, not least the fact that the term 'representative democracy' was not coined until the 1770s - Alexander Hamilton, Noah Webster, and the Marquis de Condorcet all being early adopters. Yet, as I have argued previously in this blog, James Harrington had already developed a sophisticated theory of representative democracy more than a century earlier. Markku Peltonen has since demonstrated that democracy was being positively advocated in England in the period of the commonwealth and free state (1649-1653) (Markku Peltonen, The Political Thought of the English Free State, 1649-1653. Cambridge, 2023) and Anti-Democracy in England reveals that as early as the 1640s a distinction was already being drawn between direct and representative democracy, with the former viewed entirely negatively, but the latter gaining some sympathy and support.

More broadly Cuttica argues that anti-democracy was a dominant discourse in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries; and that this was closely associated with fear of 'the mob', of 'the lower orders'. He usefully unpicks just why democracy was viewed so negatively; one crucial reason being that it was seen as worse than tyranny because it blurred the important distinction between rulers and ruled.

The other reading I have been doing this month has focused on the late eighteenth century. Hostility to democracy remained common then too - for largely similar reasons. There is also evidence that the concept of representative government underwent further exploration at this time. In Britain, particular attention was paid to what was required for representation to work effectively. In The Freemens' Magazine (1774), a text that offers a forensic examination of national and local political issues from the perspective of the freemen of Newcastle upon Tyne, the local minister and political activist Rev James Murray insisted that MPs ought to follow the instructions of their electors rather than making their own judgements on key political issues. In another text, Give us Our Rights! (1782), the leading reformer John Cartwright argued that, without annual parliaments and universal male suffrage, representative government would remain flawed.

John Cartwright by Georg Siegmund Facius, after John Hoppner, 1789. National Portrait Gallery: NPG D19015. Reproduced under a creative commons licence.

Cartwright's commitment to universal male suffrage is particularly striking in the light of Cesare Cuttica's comments about the ubiquity in the seventeenth century of the view that the poor should not have a political voice. Cartwright was explicit - and adamant - that the poor deserved to be properly represented in Parliament: 'Since the all of one man is as dear to him as the all of another, the poor man has an equal right, but more need, to have a representative in parliament than a rich one' (John Cartwright, Give us our Rights! London, 1782. p. 8). While Cartwright's view was by no means that of the majority at the time, it is striking that he was allowed to express it publicly in print. Moreover, as the quote implies, he and other reformers optimistically believed that granting universal male suffrage would, in and of itself, improve the lot of the poor. Writing in the early nineteenth century, the radical author and printer Richard Carlile reinforced this view, declaring: 'The great mass of the People of this country are not only deprived of even the least shadow of liberty, but are deprived of the necessaries of life', the means of correcting this, he argued, was 'the necessary controul of the democratic part of the Government over the other part' (Richard Carlile, The Republican, I:2, Friday 10 September 1819, pp. 34-35).

Sadly the optimism of these reformers proved unfounded in that the introduction of universal suffrage has not eradicated poverty. The franchise was extended to an increasingly wider proportion of the male population in 1832, 1867 and 1884 and to women in 1918 and 1928 - and yet the negative attitude towards the poor remained. As Cesare Cuttica notes, even Thomas Babington Macaulay, who supported the Reform Act of 1832, maintained a strong disdain for ordinary people, describing the multitude as 'endangered by its own ungovernable passions' and insisting that only those with 'property' and those endowed with 'intelligence' should be allowed to govern (Cesare Cuttica, Anti-Democracy in England 1570-1642. Oxford, 2022, p. 244). Even among those who acknowledged the need for a wider franchise, then, there remained a hostile attitude to the poor, a conviction that the poor should not be given a political voice, and an unwavering belief in the need to maintain the distinction between rulers and ruled.

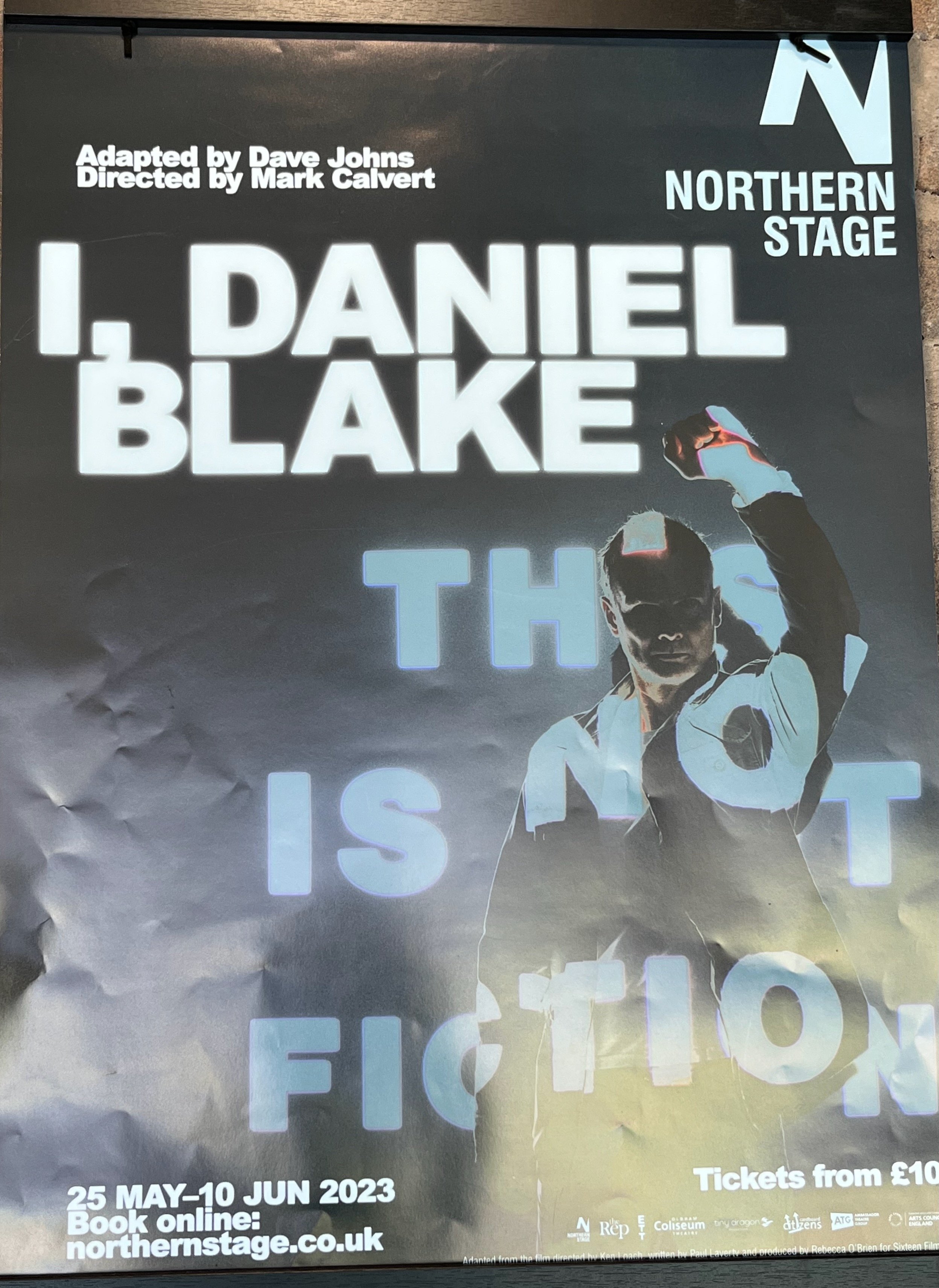

Poster for the stage version of ‘I, Daniel Blake’ at Northern Stage in Newcastle. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

As recent events have proven yet again, many among the political elite continue to view the poor with disdain. The lives of the poorest and most vulnerable in our society also continue to worsen, after having improved somewhat in the second half of the twentieth century. A recent BBC feature on the opening of a stage version of 'I, Daniel Blake', at Newcastle's Northern Stage theatre, suggested that since the launch of Ken Loach's film in 2016 the demands on food banks in Newcastle have increased considerably. Moreover, there have been repeated incidents suggesting that many MPs think different rules apply to them than to the rest of the population. These include: the expenses scandal; the failure of some Government ministers to adhere to Covid restrictions during the pandemic; and the suggestion that the Home Secretary's traffic offence ought to be handled differently from the standard rules that apply to anyone else who is caught speeding. Furthermore, while universal suffrage is not generally challenged, continued attempts are made to silence the political voice of the poorest and most vulnerable. The new rules on voter identification introduced at May's local elections undoubtedly create more of an obstacle for the poor, who are less likely to be in possession of a passport or driving licence, than the rich.

Cesare Cuttica is right to highlight both the importance of anti-democratic thought in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and to pinpoint the opening up of a cleavage between direct and representative democracy occurring as far back as the 1640s. But it is also the case that the very idea of representation has subsequently been used to reinforce the assumption that political participation is, or should be, restricted to the middle and upper classes, and by these means to turn down - even silence - the political voices of the poor. We need to overcome the lingering effects of political prejudices that date back at least to early modern times.