Economic inequality is a perennial issue. Recent news items have reminded me of this, and of the fact that it has sometimes been justified by appeal to the arguments of eighteenth-century writers, notably Adam Smith. This misconceives what he actually wrote, and ignores the arguments of other eighteenth-century thinkers - such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau - against economic inequality.

Image from Wikimedia Commons.

In advance of last week's budget there was much speculation as to whether Rachel Reeves was going to break Labour's manifesto pledge and raise income tax. Public services are currently struggling and raising the tax paid by those in the additional rate band (who earn over £125,140 of taxable income per year) and in the higher band (those earning £50,271 to £125,140) would have been the most straightforward way of providing a welcome boost to the public finances. Taxing those in the top two bands more heavily would also have served to reduce the growing inequalities in income within our society.

The Labour Market Statistics published by the Office for National Statistics in October reported that the mean average weekly wage (including bonuses) is £733 before tax - equating to an annual pre-tax average salary of around £38,100. Yet, as Forbes Magazine noted, this hides huge inequalities between individuals. The median annual pay of top chief executives was £4.22 million in 2024, while three million UK workers earn the minimum wage (£12.21 for those over 21, £10 for those aged 18-20 and £7.55 for those aged 16-17) (https://www.forbes.com/uk/advisor/business/average-uk-salary-by-age/#overview_of_earnings_in_the_uk); amounting to around £25,000 a year at best.

Image of Elon Musk from Wikimedia Commons.

Another story this month that highlighted the issue of extreme inequalities in income was the announcement on 7th November that Tesla shareholders had approved a record breaking trillion dollar pay package for Elon Musk (already the world's richest man). The package is dependent on the company raising its market value over ten years and hitting various targets, and Musk will be paid in shares, but it is still an obscene amount of money to award to an individual. The Tesla board justified the deal on the grounds that it feared that without that incentive Musk might leave the company and it could not afford to lose him.

The notion that the outrageous salary package offered to Musk is necessary to keep him at Tesla draws on the argument that it is better for companies (and by extension for society) to keep rich people on side because vast inequalities of wealth within a society actually benefit everyone. Drawing on a (skewed) understanding of Adam Smith's thought, the theory of 'trickle-down economics' reassures us that we are all better off as a result of the huge salaries of the rich. Smith's theory of the invisible hand is taken as an excuse to reject state intervention in income distribution on the grounds that it is likely to be counterproductive (https://www.adamsmithworks.org/documents/adam-smith-peter-foster-invisible-hand). Yet, as research by David Hope and Julian Limberg has shown, tax cuts for the rich tend to result in further benefits for them rather than improving the lives of workers or stimulating economic growth (https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/107919/1/Hope_economic_consequences_of_major_tax_cuts_published.pdf).

Street sign from Geneva commemorating Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Image by Rachel Hammersley.

While those who argue that vast inequalities in wealth are good for society sometimes seek eighteenth-century roots for their argument, the counter-argument - that growing inequality has negative rather than positive consequences for society as a whole - was also explored at that time. In his Social Contract Jean-Jacques Rousseau insisted on the need for relative equality within a successful state:

as for wealth, no citizen be so very rich that he can buy another, and none so poor

that he is compelled to sell himself: Which assumes, on the part of the great,

moderation in goods and influence and, on the part of the lowly, moderation in

avarice and covetousness.

In a footnote Rousseau continued:

Do you, then, want to give the State stability? Bring the extremes as close together

as possible; tolerate neither very rich people nor beggars. These two states, which

are naturally inseparable, are equally fatal to the common good; from one come the

abettors of tyranny, and from the other tyrants; it is always between these two that

there is trafficking in public freedom; one buys it, the other sells it. (J. J. Rousseau,

Of the Social Contract, ed. V. Gourevitch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1997, p. 78).

For Rousseau, then, great inequalities of wealth within a state would encourage tyranny and corruption.

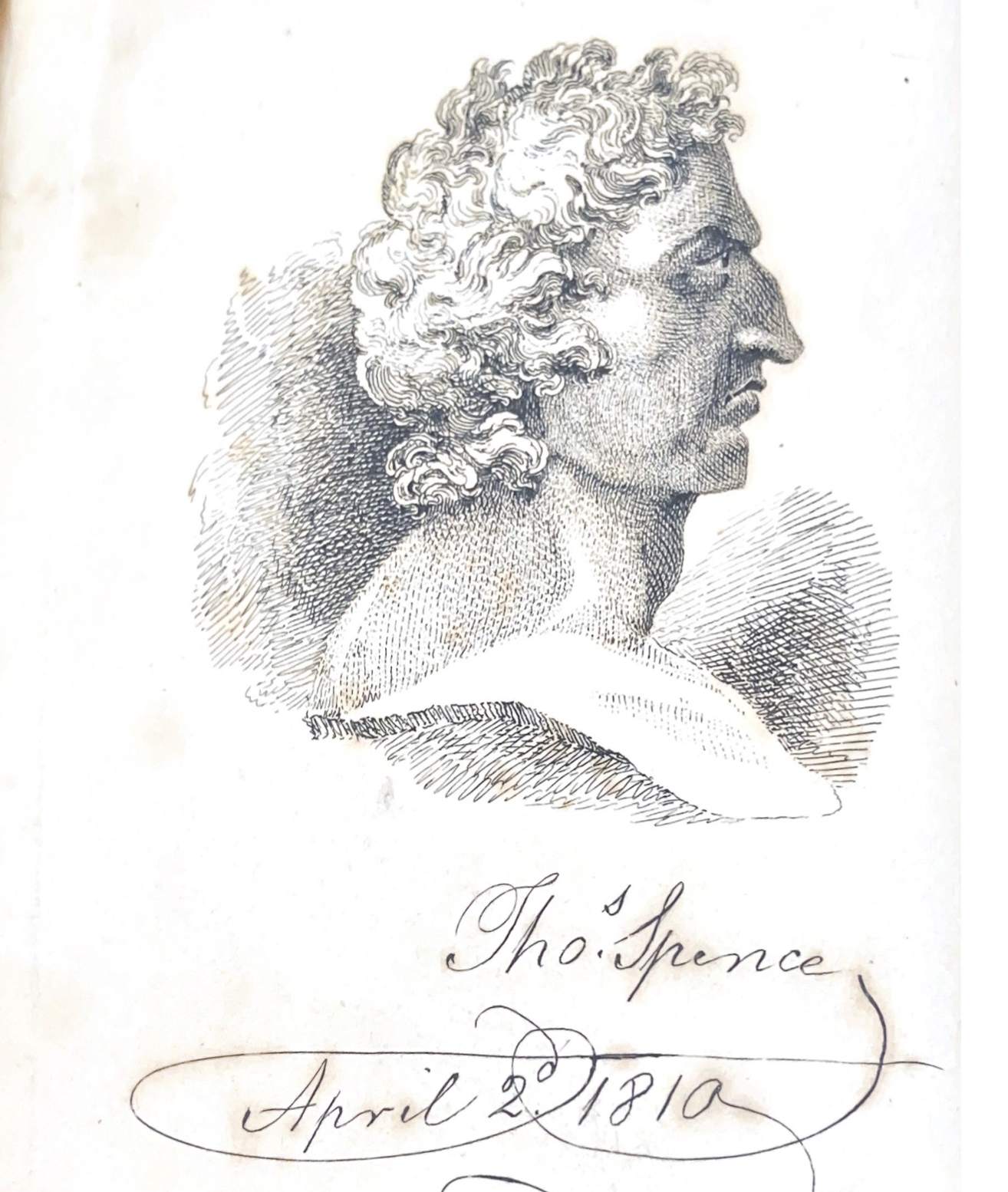

Writing just over thirty years later, the Newcastle-born radical Thomas Spence expressed a similar view. He observed the growing inequalities in British society:

Great landlords, and great farmers, now engross the country and these employ

none but great tradesmen. No little masters to be seen now, no medium; but very

great, and very little; very rich, and very poor. (Thomas Spence, 'A Letter from

Ralph Hodge, to his Cousin Thomas Bull, in The Political Works of Thomas Spence, ed.

H. T. Dickinson. Newcastle: Avero, 1982, p. 22).

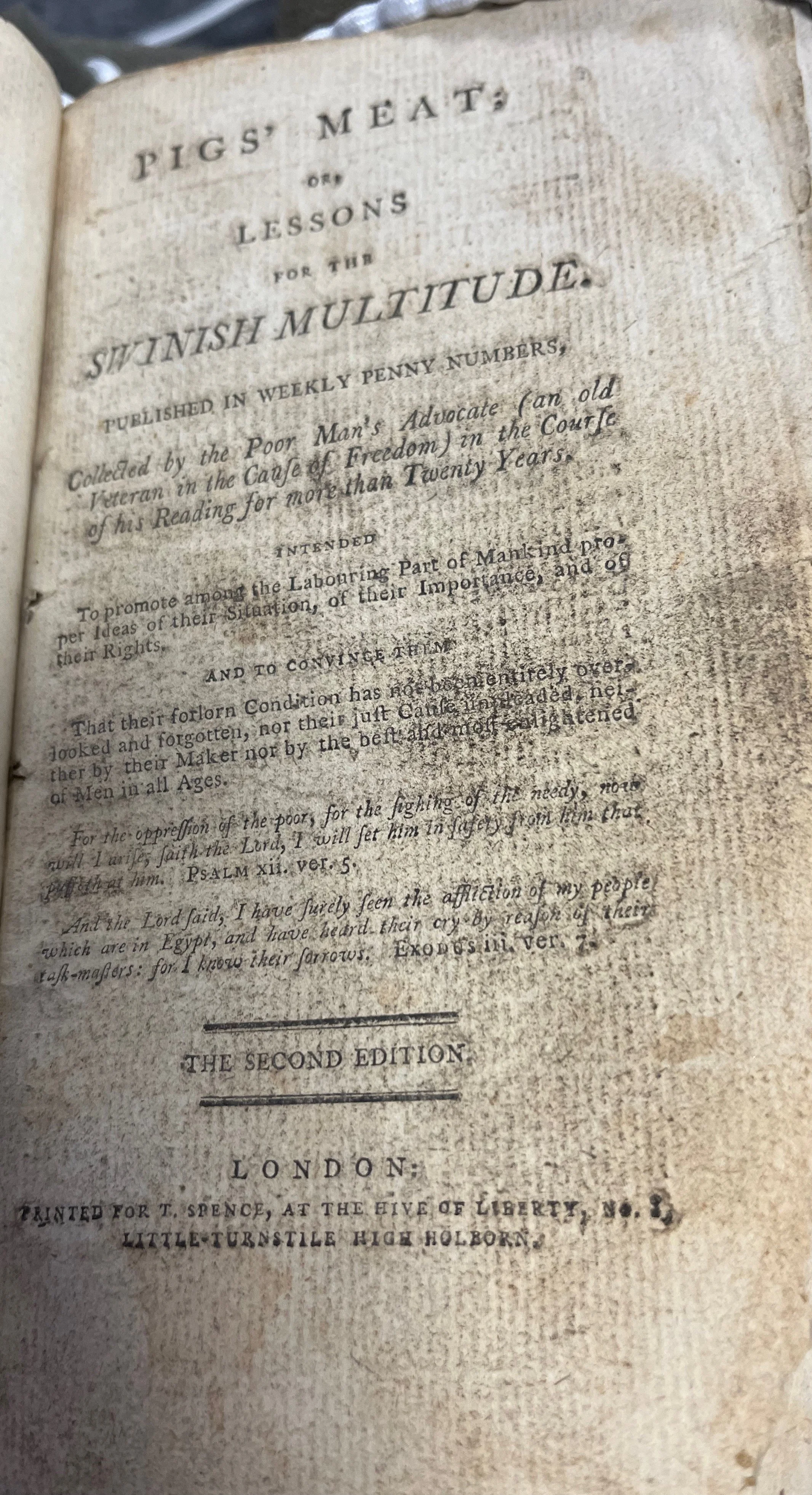

In contrast to the theory of 'trickle-down economics', Spence insisted that a more equal division of property was the way to ensure that all had the necessities of life. Under the heading 'A Lesson for Antigallicans' he reprinted the following extract from a contemporary pamphlet in his journal Pigs' Meat:

Title page of Thomas Spence’s periodical Pigs’ Meat (London, 1793). Copy from the Philip Robinson Library, Newcastle University. Reprinted with kind permission.

if property were divided with any tolerable equality, a man would begin by

providing amply for his support, comfort, and enjoyment; and would only suffer

the surplus to be exchanged for foreign superfluities; nor would he for superfluities

condemn himself to incessant labour. (Thomas Spence, Pigs' Meat. London, 1793, p.

18)

Similarly in an earlier work of his own, in which he imagined an island society where land was owned collectively, Spence has his narrator observe of the island:

instead of anarchy, idleness, poverty, and meanness, the natural consequences I

narrowly thought of a ridiculous levelling scheme, [there is] nothing but order,

industry, wealth, and the most pleasing magnificence. (Thomas Spence, A

Supplement to the History of Robinson Crusoe. Newcastle upon Tyne, 1782, p. )

On what grounds did these thinkers argue that excessive inequality is bad for society? They claimed that as the gap between rich and poor increases, the pursuit of money comes to be valued more than the promotion of the common good. As a result, wealth starts to be viewed as a marker of merit regardless of the means by which that wealth was gained. In the language of the eighteenth century, people start rising to power simply because they are rich rather than because they are virtuous. Looking at the world today, I cannot help feeling that we are well past that point.

For eighteenth-century thinkers, the solution to this problem was easy to understand, though not necessarily straightforward to implement. If excessive inequalities of wealth within society were dangerous to the public as a whole, then it was incumbent on the government to introduce some degree of redistribution of wealth to keep those inequalities in check. This would ensure that the government operated in the public interest.

Image of Spence from the Hedley Papers at the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society. Reproduced with kind permission.

Spence took a rather extreme view of what this government intervention should involve. While he did not call for the abolition of moveable property, believing this was a spur to industry, he did insist on the communal ownership of land (organised at the level of the parish). That proposal was ridiculed in his own time and seems even less like a workable solution today. But we do have a ready-made system that is designed to allow the government to redistribute wealth in the interest of the public good and to keep a check on the inequalities of income between the richest and poorest in society. That system is income tax. What a shame Rachel Reeves did not find the courage to pull that lever last week.