Is what I am doing worthwhile? How can I make a difference? I often ask myself these questions. They feel especially pressing in the midst of the current cost of living crisis, in the face of impending environmental disaster, and in a situation of growing inequality both within Britain and between us and the global south. In this context, writing books and articles on obscure early modern figures and their ideas - and teaching classes to students who are relatively privileged - can feel self-indulgent. It was, therefore, reassuring to learn from Penny Corfield, at a recent conference to celebrate 50 years since the publication of The World Turned Upside Down, that the eminent early modern historian Christopher Hill was troubled by these questions too. Like me, Hill was no doubt partly prompted by the inspiring phrase from Gerrard Winstanley, which I have quoted before in this blog: 'action is the life of all, and if though dost not act, though dost nothing' (Gerrard Winstanley, A Watch-Word to the City of London and the Armie, London, 1649).

The programme for the conference, which was expertly organised by Waseem Ahmed in conjunction with John Rees.

In his excellent paper on Hill's life and thought, which marked the culmination of the conference, Mike Braddick explained that as a young man in the 1930s Hill was already 'thinking like a Marxist' but did not yet know what to 'do'. Of course, he soon found his role. As Mike explained, writing history was Hill's contribution. As one obituary of him noted, Hill was 'an historian's historian' and yet works like The World Turned Upside Down spoke not just to academics, but also to ordinary people. Moreover, as Ann Hughes explained in her paper, Hill also reached out in many different ways to a wider public through his involvement with organisations such as the Workers' Educational Association, the Open University, and the BBC. I was bemused to learn that Hill's piece 'James Harrington and the People' was originally written for radio. Oh if only someone would commission a radio programme on Harrington today! Similarly John Rees reported, on the basis of his own experience, that Hill was always happy to be associated with the organised left and gave inspiring speeches to large crowds.

There is an interesting parallel between Hill's commitment to venture beyond academia, presenting his historical research (and that of others) to the general public, and the subject matter of The World Turned Upside Down. That book took seriously the ideas of ordinary people. Its protagonists are not the 'great' thinkers of the seventeenth century but rather the ordinary people (some of them very humble indeed) who were caught up in events. Hill was interested in ideas that inspire practical political action, regardless of the social status or level of education of those who voiced those ideas and took that action.

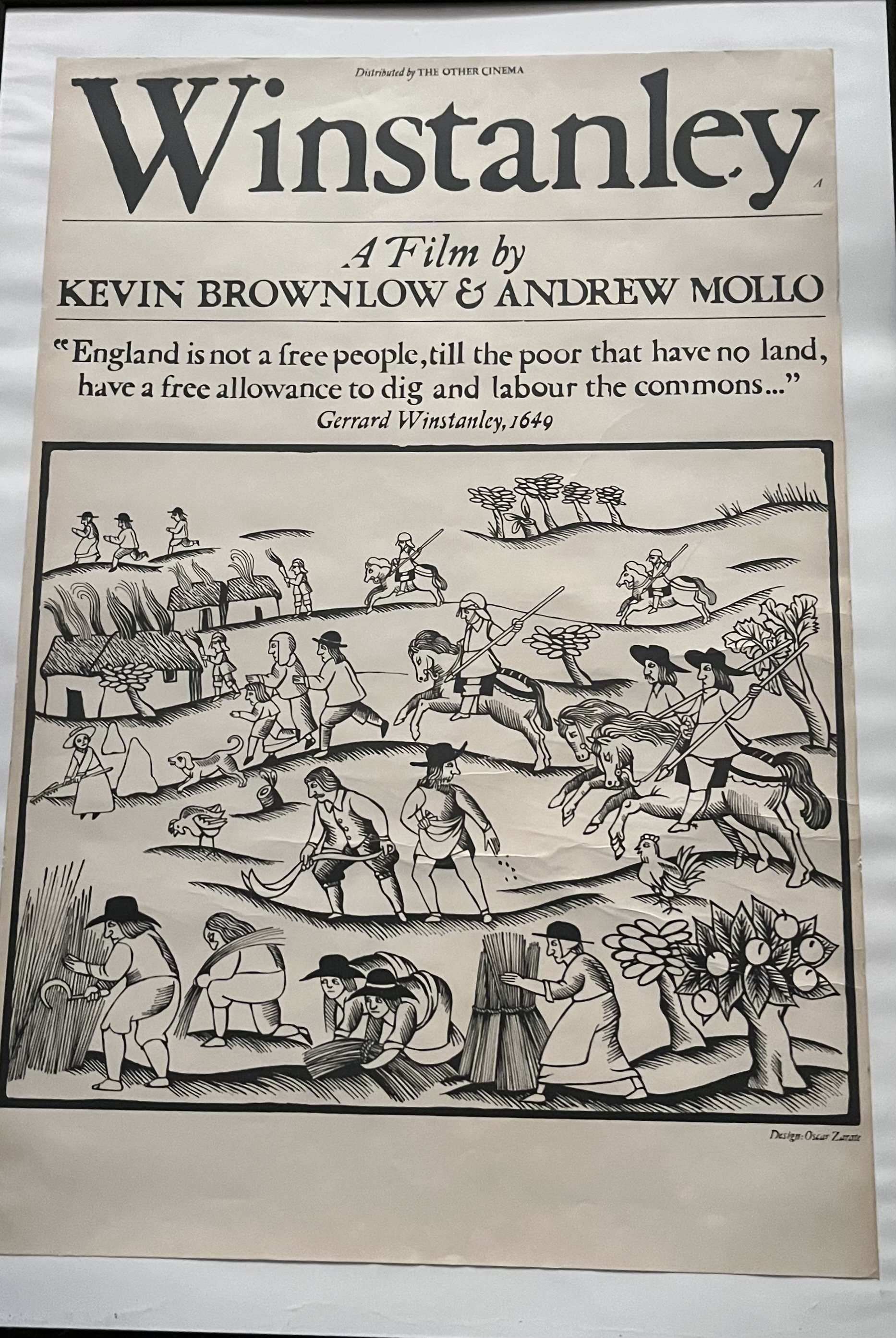

A poster advertising the film Winstanley about the Digger movement, one of the key groups to feature in Christopher Hill’s The World Turned Upside Down. Author’s own copy.

This focus was reflected in several of the papers at the conference, including papers that dealt with figures who feature in The World Turned Upside Down and papers on those who perhaps should have done, but do not. It was apt to have Ariel Hessayon talking about the Ranters and Bernard Capp to say something about the Fifth Monarchists. Ariel contextualised Hill's account of the Ranters in The World Turned Upside Down and emphasised the fact that the strength of Hill's book lay in making these rather obscure figures visible. He also noted that Hill came to the Ranters quite late. Capp extended this point, acknowledging that the radicals are not prominent in many of Hill's earlier works such as The English Revolution 1640 and The Century of Revolution (though this partly reflects the nature of those publications). Capp also suggested that the Fifth Monarchists and Muggletonians ranked lower in Hill's estimations than the Ranters and the Diggers, not least because their ideas did not all sit comfortably with his understanding of radicalism.

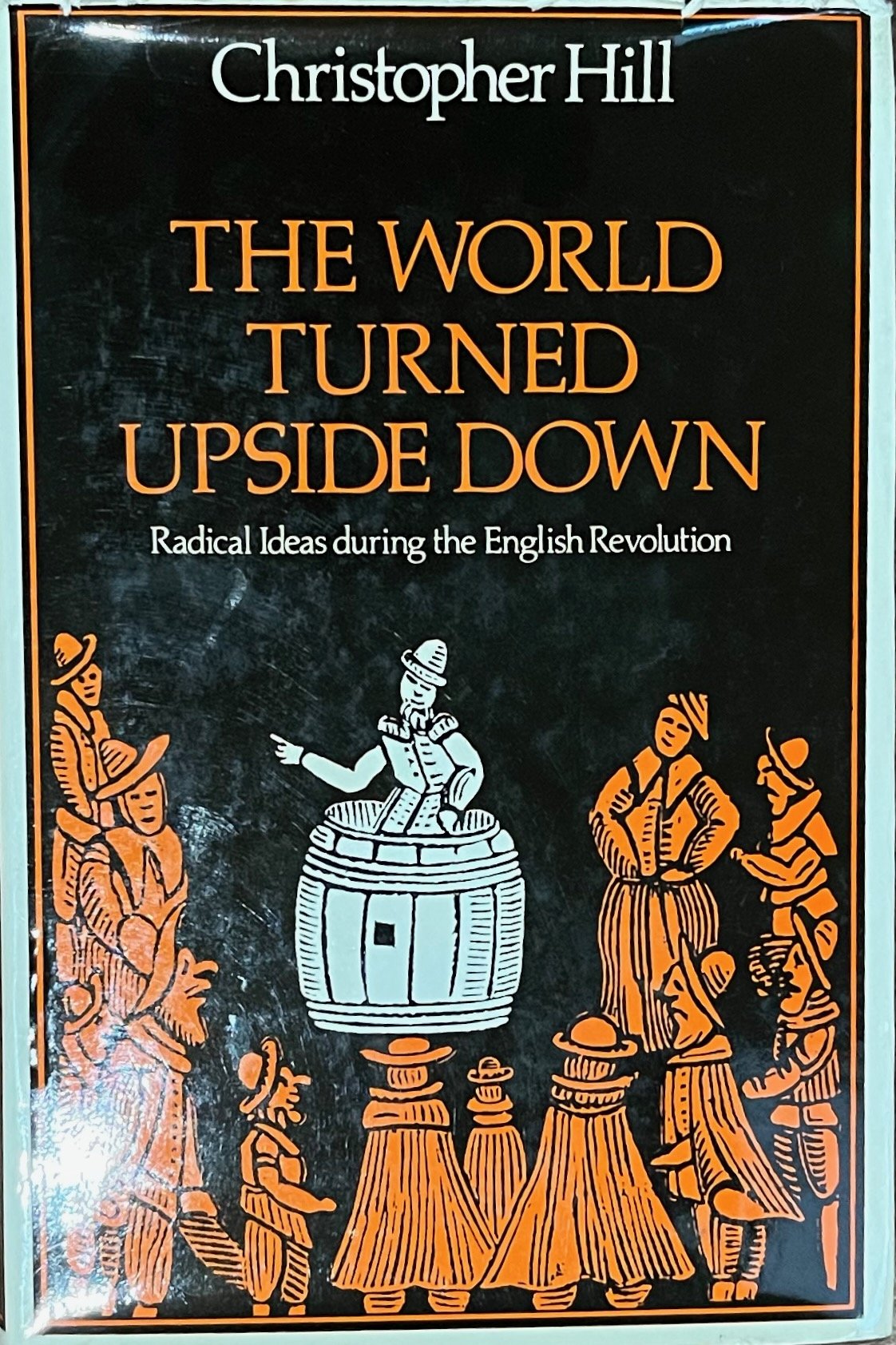

Author’s copy of Hill’s book showing the tub-thumping preacher on the cover.

Several speakers made the case for particular individuals to be considered as radicals. Jackie Eales's paper focused on the radical preacher James Hunt of Sevenoaks, who does not appear in The World Turned Upside Down despite probably being the tub-thumping preacher on the cover of the original edition. Jason Peacey argued the case for George Wither and asked the thought-provoking question: How would our view of radicalism change if Wither were taken more seriously? Ed Legon's paper focused on individuals even more obscure than Hunt and Wither, textile workers-cum preachers such as one Thomas Moore, 'Dingle', and others for whom we do not even have a name. The link between textile workers and radical puritanism has long been recognised, if not fully explored, but other speakers found radicals in even more unexpected places. Will White made the case for the neutral Francis Nethersole as a radical of sorts. He pointed out that refusing to take sides was itself a political act, which might lead to disobedience and required considerable courage. He also noted the similarities between ideas put forward by Nethersole to justify his neutrality and those expressed by the Leveller William Walwyn in The Bloody Project. The fluidity implicit in Walwyn's position (and acknowledged by Hill) was also reflected in the activities of another Leveller, Captain William Bray, who was the subject of Ted Vallance's paper. Ted showed how Bray haunted the boundary between the Levellers and the Ranters. In part, this fluidity stems from thought being geared to political action, since engaging in politics (rather than merely contemplating it) may require pragmatism: deploying different arguments for different audiences; rearranging priorities in response to events; and even setting aside key principles at certain moments.

The image of the world turned upside down from the pamphlet of the same name.

This leads to another point that was reflected in both Hill's life and his work. The importance of free and open debate, and even the possibility that ideas might be changed through it. As Ann, John and Mike all noted, Hill experienced this himself in the debates in which he engaged as a member of the Communist Party Historians’ Group between the late 1930s and 1957. The idea of open debate was also reflected in papers that themselves turned conventional interpretations upside down. For example, Richard Bell showed that the interest of key Levellers in prisons was not a case of them bringing political consciousness to prisoners, but rather of the Levellers tapping into a long-standing campaign for prison reform. Similarly, Laura Stewart made a convincing case for the notion of a Scottish Revolution, emphasising the need for it to be understood on its own terms.

Laura's paper was one of many that either ventured beyond Hill's field of enquiry or even challenged key aspects of his thought. As Penny Corfield made clear, Hill would have enjoyed and appreciated the debate. He welcomed respectful disagreement on the grounds that thinking could be advanced in the process. As Mike explained, the members of the Communist Party Historians’ Group were not aiming to impose an orthodox view of the English Revolution but rather engaged in lengthy, deep and open discussion to try to work out the relevance of Marxist theory for English history. For Hill it was important that ideas were debated and kept in use.

Sketch of the bust of Thomas Spence. From the collection of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne. Hedley Papers. Reproduced with kind permission. With thanks to Harriet Gray.

The conference papers and discussions certainly inspired me, helping me better to understand and articulate the meaning of my own life and work. I too am committed to analysing not simply the ideas of great political thinkers of the past, but also those of ordinary people caught up in events. My PhD research examined the ideas of relatively humble French revolutionaries who were members of the Cordeliers Club, and considered the ways in which they adapted English republican ideas to their own situation. In my current research I am exploring how reformers and radicals in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain articulated their arguments. In this regard, the Newcastle-born radical Thomas Spence is of particular relevance. Despite being from a very humble background, Spence developed innovative political ideas of his own and believed strongly in the value of providing political education to all members of society, regardless of their wealth or social status.

At the same time, I am committed to engaging with audiences beyond academia. I have been involved with a number of exciting projects alongside our excellent educational outreach team from Newcastle University's Robinson Library and staff at the National Civil War Centre. Our current project involves working with Year 12 students on oracy and debate. Meanwhile, the Experiencing Political Texts project (https://experiencingpoliticaltexts.wordpress.com) has provided an opportunity to work with members of the public in a regular reading group where discussions are always thought-provoking. We will develop this further as we put together two exhibitions, one at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University this summer and another at the National Library of Scotland, opening in December. Finally, this blog has provided a valuable opportunity to share my research with a wider audience, but also to reflect on the implications of the ideas of the past today. I can only dream of producing a book like The World Turned Upside Down, but by taking seriously the ideas of all people - including those who have so often been silenced - perhaps I can make a small contribution and heed Winstanley's injunction to 'act'.