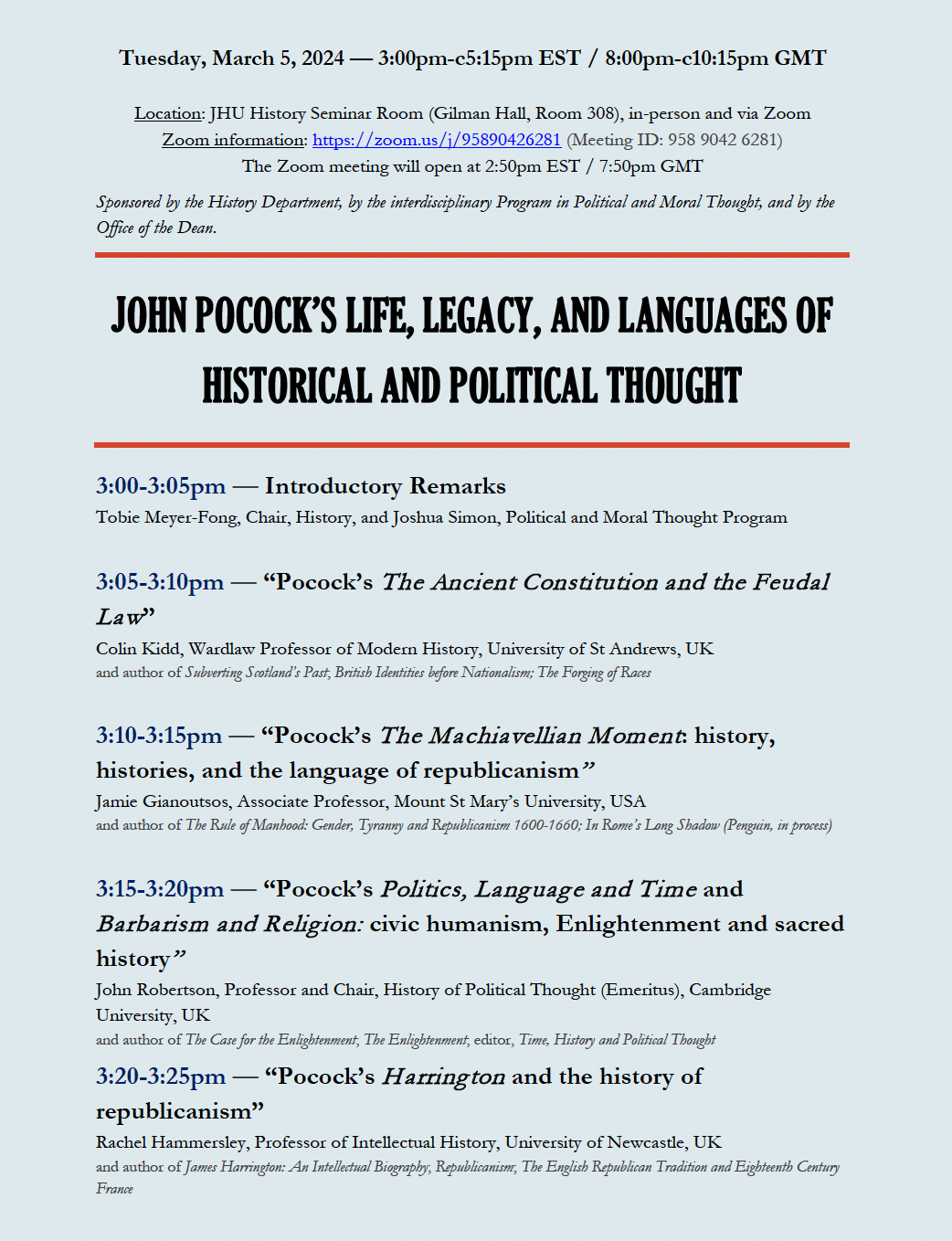

When I was invited in 2019 to tweet a book a day for a week I had no hesitation as to what my first book would be. John Pocock's The Machiavellian Moment was probably the single biggest influence on me as a student, directly affecting the direction my research has taken. For this reason I was thrilled later that year when, just before the publication of my Intellectual Biography of James Harrington, I received one of John Pocock's beautiful handwritten letters expressing his interest in my forthcoming book, which initiated a brief correspondence between us. Following Pocock's death at the age of 99 in December 2023, I was honoured to be invited by John Marshall to contribute to 'John Pocock's Life, Legacy, and Languages of Historical and Political Thought', which was held simultaneously at Johns Hopkins University and online on Tuesday 5th March 2024.

Having initially reassured John Marshall that I relished the challenge of saying something meaningful about 'Pocock's Harrington and the history of republicanism' in less than five minutes, I did subsequently question my initial enthusiasm. The reality of drafting something worthwhile that did not breach the time constraint was tough. It was, though, very illuminating to hear the other speakers perform equally impossible tasks of summarising Pocock's thoughts on a range of topics including the Italian Renaissance, the Enlightenment, Edward Gibbon, and Edmund Burke in less than five minutes each. Papers were presented by scholars at all levels, from PhD students to Emeritus Professors; and the event closed with three excellent questions by graduate students currently studying at Johns Hopkins. The organisation of this event was largely down to John Marshall (though with a supportive team around him). His vision for the event and his dedication to making it a success were impressive. What follows, provides a taste of what I gained from this ambitious celebration. Anyone who missed the event, and would like access to the recording, can contact John Marshall directly.

What came across more than anything else was John Pocock's phenomenal intelligence and the breadth and depth of his scholarship. Eliga Gould, speaking on behalf of Pocock's students, put it well when he referred to the capaciousness of his work and vision. During the course of his lifetime, Pocock offered groundbreaking insights on a whole host of individual figures while also making significant contributions to broader fields of study. These included the Enlightenment - where he put a persuasive case for thinking in terms of a plurality of Enlightenments rather than a single Enlightenment. He also contributed to the transformation of British History by challenging the dominant Anglocentric emphasis, calling for the inclusion of the histories of Scotland and Ireland, but also Wales, Cornwall, the Channel Islands, America (pre-1776) and, of course, his native New Zealand. Equally important was his stress on the tensions and interplay between metropolitan zones of law and marcher zones of war. In addition, Pocock set the terms for the study of the history of republicanism: emphasising and unpicking the ancient legacy; highlighting the centrality of the conception of time to republican thinking; and prioritising the vocabulary or language of republicanism over institutions.

Despite the breadth, it is possible to identify consistent threads that run throughout Pocock's thought. One was his robust approach to historical research, which - as was noted by David Bromwich (in relation to Burke) and John Marshall - involved reading all the works available by a particular author in order to enter into the thinking of those who interested him. He also adopted a broad approach to sources, consulting manuscripts as well as printed material, treating style as important (David Womersley commented on this in relation to Gibbon), and recognising that political 'sources' could take a variety of forms including literature and - as Anna Roberts noted - even artefacts.

Central among the sources Pocock himself deployed were histories. His first work The Ancient Constitution and the Feudal Law was a major achievement in the field of historiography. As Colin Kidd explained, it documented ideological uses of the past, treating historical thinking as political thinking. For Kidd this exposed a space between politics and the history of political thought in the form of the history of political argument. Pocock returned to this territory in the magnum opus of his later years, the multi-volume account of the thought of Edward Gibbon, Barbarism and Religion. Both here, and in his works on other individual thinkers, Pocock sought to identify and understand the political and intellectual battles in which those thinkers were engaged.

While The Ancient Constitution and Barbarism and Religion are the works that most obviously treat historical writings as political thought, the preoccupation with history and time also lay at the heart of Pocock's other major work The Machiavellian Moment. In the first place, the conception of time is presented as crucial to republics in that they exist in time and are, therefore, subject to corruption and decay. This was what Pocock meant by the 'Machiavellian Moment'. He argued that Machiavelli was particularly concerned with 'the moment in which the republic confronts the problem of its own instability in time' and explored how this idea played out in the writings of others in Renaissance Italy, seventeenth-century England, and eighteenth-century Britain and America. In adopting this broad chronology, the book also examines the survival - and transformation - of ideas over time. While there is continuity in terms of the central problem being confronted and the vocabulary deployed to address it, the republican language at the heart of the book was adapted to fit different circumstances and Pocock was sensitive to the particular historical contexts that prompted the production of specific texts. The adaptations are especially evident in the case of James Harrington. He drew on Machiavellian ideas to construct an immortal commonwealth - which Machiavelli would have declared an impossibility - and his ideas were in turn deployed by those Pocock labelled 'neo-Harringtonians' in ways directly contrary to Harrington's intentions.

Pocock's intelligence, and the breadth of his scholarship, could make him appear intimidating, yet he tempered this with a deep humanity - and this also came out strongly in the presentations. Again and again, contributors spoke of the personal impact he had had on them and commented on the fact that, while he was challenging, he was also generous, encouraging, and fun (the last being exemplified by the fact that his sons Hugh and Stephen chose to begin their contribution with a song). Eliga Gould spoke of him having a personal and unique relationship with each of his graduate students, but it is clear that his intellectual relationships extended well beyond those who had the special privilege of being taught by him. Indeed, it was striking that one of the older contributors, Orest Ranum, who had been on the committee that appointed Pocock to his position at Johns Hopkins in 1974, described him as a constant teacher - instructing not just students but all those with whom he came into contact. Another Johns Hopkins colleague, Christopher Celenza spoke for many when he described the privilege of being taken seriously by Pocock - even when this meant disagreement. The possibility that polite disagreement could co-exist alongside friendship and respect, was also highlighted by perhaps Pocock's closest intellectual companion, Quentin Skinner, who admitted in his talk that he never succeeded in convincing Pocock on the subject of liberty. He was, then, as Jamie Gianoutsos articulated, not only a careful student of republican vocabulary, but also a model citizen himself.

I hope I have conveyed the fact that this event was deeply moving, instructive, and inspiring. I was, though, left with a slight sense of regret. Skinner recalled that in 1973 Pocock announced that he had a plan for a huge new project. It would explore all of British historical and political thought from Bede to Bertrand Russell. The scale and ambition of such a project reflects the massive breadth of John Pocock's vision and the strength of his drive, but perhaps also explains why it never came to fruition. I don't suppose I was the only person at the event who took a moment to lament this fact. I would have loved to read it.