Last month I wrote about the 'Translating Cultures' workshop that I attended at the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, Germany in late June 2018. The same week I also spoke at the Graduate Conference in the History of Political Thought held at UCL in London. The theme this year was 'Representation and Misrepresentation' and I was honoured to be invited to deliver the keynote address. Unfortunately, I was only able to attend the first five panels, but I heard some fascinating, inspirational papers that led me to reflect on several key themes.

One of these was the sheer complexity of the concepts 'representation' and 'misrepresentation'. This complexity has a long history. While representative government is often associated with modern democracy - with representation presented as a means of making democratic government workable in large modern nation states - Ludmilla Lorrain reminded us that representation was originally developed in opposition to democracy. Late eighteenth-century advocates of representative government - for instance, the American founding fathers, Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès and Edmund Burke - believed democracy ought to be avoided, and instead celebrated representative government as superior. In this context, Lorrain argued, William Godwin's commitment to 'representative democracy' is worthy of investigation.

Benjamin Constant, as Arthur Ghins demonstrated, sided with Sieyès and Burke rather than Godwin. The advantage of representation for Constant was not that it made democracy possible, but rather that it would result in good political decisions. Ghins also argued that Constant was more concerned with representing interests than individuals, further complicating what we understand by political representation.

John Stuart Mill, replica by George Frederick Watts, 1873. National Portrait Gallery NPG 1090. Reproduced under a Creative Commons License.

The question of who or what was to be represented was always contentious, and from the French Revolution onwards some claimed that representation ought to extend to women as well as men. John Stuart Mill was a particularly strong advocate of this claim. In her paper, Stephanie Conway argued for the centrality of this commitment within Mill's thought. Mill, she suggested, believed that the enfranchisement of women would solve the pressing problem of overpopulation.

Alongside who should be represented, the tools used to exercise representation have also proved contentious. The timely issue of the uses of referenda in representative governments was explored by Gareth Stedman Jones, in his introductory address, and by Ariane Fichtl. Opening her paper with a reference to Jacques Louis David's painting 'The Oath of the Horatii', Fichtl noted that the Horatii were eventually acquitted after an appeal to the Roman popular assembly. Yet in 1792 it was the Girondins, rather than David's allies the Jacobins, who advanced the idea of referring the decision about what should be done with the former French king to the people. Stedman Jones noted that under both Napoleon III and Hitler referenda were used as a means of providing apparent democratic accountability in systems that were some way from being democratic.

Jacques-Louis David, 'Oath of the Horatii', 1784. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:David-Oath_of_the_Horatii-1784.jpg

Sir William Temple, Bt., after Sir Peter Lely. Based on a work of c.1660. National Portrait Gallery NPG 152. Reproduced under a Creative Commons License.

As well as causing me to reflect on the complexities of representation, the papers also encouraged me to think about the nature of the history of political thought as a field. In the first place it is clear that the importance of examining works in their historical and intellectual context - as pioneered by the Cambridge School - remains a useful and revealing methodology. Interestingly, it was, perhaps, the speakers from the European University Institute in Florence who displayed the richness of that approach most eloquently. Bert Drejer explored the revisions that Johannes Althusius made to the 1610 and 1614 editions of his Politica, methodice digest in response to changing circumstances. Moreover, in answering questions he noted that part of the reason for Althusius's greater emphasis on cities in the later editions was probably that he had become a syndic himself in the intervening period. Juha Haavisto is writing an intellectual history of William Temple and very much seeking to set Temple's thought in its context. He described Temple as a practical and pragmatic writer whose lack of consistency can be explained by the fact that he often adapted his thought to the circumstances. Elias Buchetmann is working on a contextual reading of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's philosophy. He argued that Hegel's observation of events in Württemberg, particularly the constitutional crisis of 1815-19, had a significant impact on the development of his thought. Morgan Golf-French also touched on this approach in his question to Ghins regarding the relationship between Constant's liberalism and his knowledge of, and engagement with, the German context.

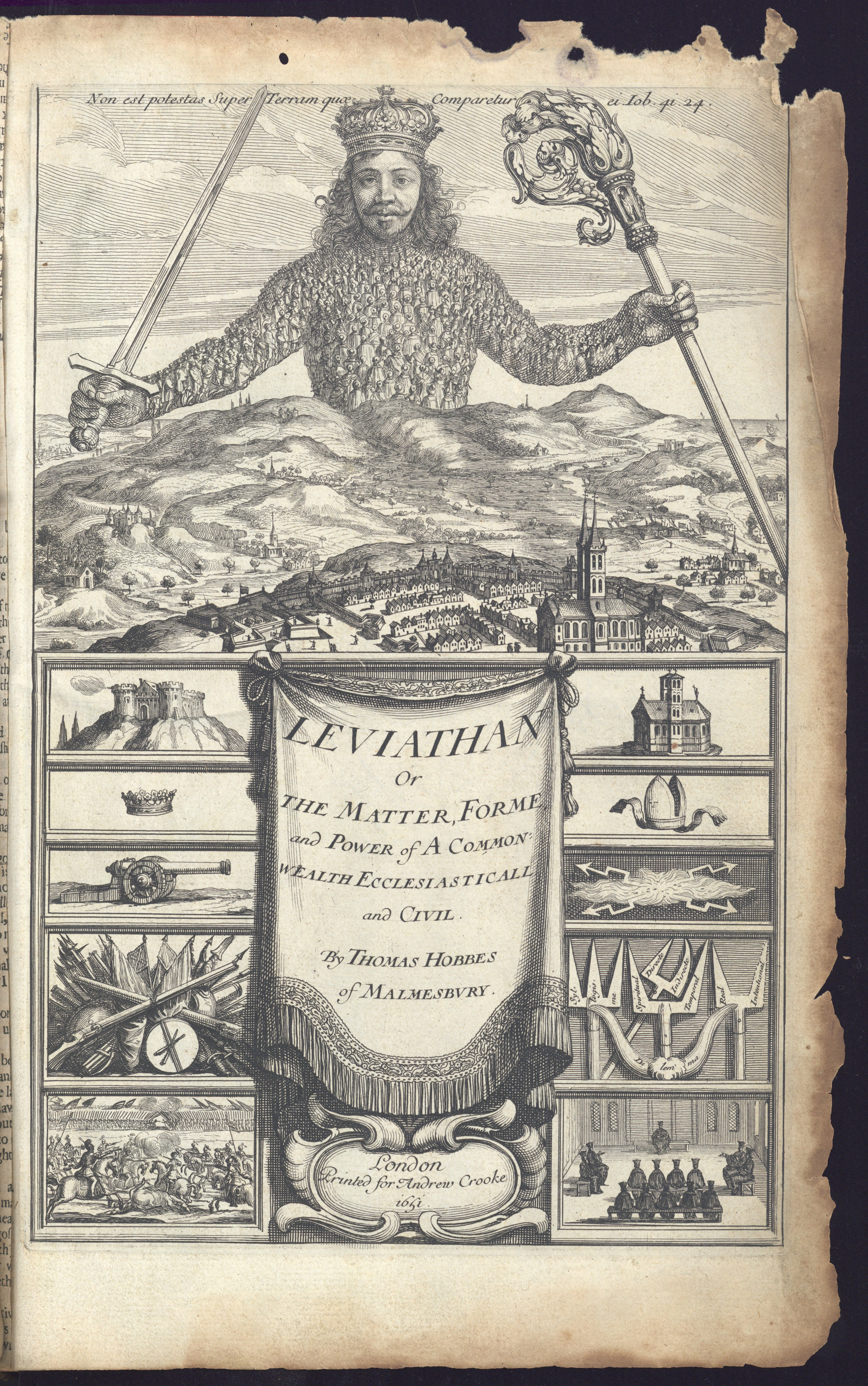

Frontispiece to Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan with its image depicting the state literally representing or embodying the population. Reproduced with permission from Robinson Library, Newcastle University. Special Collections, Bainbrigg (Bai 1651 HOB).

While suggesting much continuity, these papers also showed signs of new developments and trajectories in the history of political thought. In particular, it is clear that there is a growing tendency towards branching out from politics, narrowly defined, to explore the interrelationship between politics and other fields of knowledge. The 2009 book Seeing Things Their Way put forward a two-pronged argument: that advocates of the Cambridge School have often ignored or downplayed the religious dimension of earlier thought; and yet that their methodology is particularly conducive to understanding and making sense of religious beliefs and convictions in their own terms (Seeing Things Their Way: Intellectual History and the Return of Religion, ed. Alister Chapman, John Coffey and Brad S. Gregory. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009). Building on this idea, Connor Robinson reminded us that debates about the polity took place within the church as well as the state in seventeenth-century England. He suggested that ideas of representation in that period might usefully be read against the background of Protestantism, showing that the ideas and practices of the early church were central to the responses that James Harrington and Henry Vane made to Thomas Hobbes. Barret Reiter also linked political and religious thought, presenting Hobbes's interest in the problem of idolatry as part of a much wider concern with the fancy or imagination. The root of Hobbes's concern with idolatry, Reiter argued, lay in the individual following his own imagination rather than obeying the sovereign.

Other papers touched on other relationships. Alex Mortimore examined the way in which political ideas could be expressed in literary form, specifically in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's work Die Aufgeregten (The Agitation), which was written in 1792 at the height of the French Revolution. I was particularly struck by the subtitle of this work 'A Political Drama' and wondered whether this was a common genre at the time or whether it was prompted by Goethe's reaction to this highly charged political moment. The paper served to remind us that literary sources can be just as valuable as political texts in reflecting the political views being expressed and debated at particular points in time.

Economics is another discipline that is closely related to politics and that was often not fully distinguished from it in earlier periods. Both Ghins's paper and that by Henri-Pierre Mottironi explored the interrelationship between politics and economics in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Mottironi demonstrated that the French Physiocrats modelled their ideas of citizenship, taxation, and representation on practices that were well established in corporate institutions, including joint stock companies such as the French East India Company. Sieyès then derived his understanding of these same concepts from the Physiocratic model and embodied them in his constitutional proposals many of which were reflected in the French constitution of 1791. While convinced of this borrowing, I was also struck by the tension that this brings to light between what revolutionaries like Sieyès were claiming and what they were doing. Sieyès set out to replace the unjust and unequal organisation of French society around corporate bodies such as the Estates with a more equal and rational system centred on individuals. Yet Mottironi's work suggests that in the very conception of this new rational model Sieyès was himself drawing on practices that operated in corporations like the joint stock companies.

Perhaps it is precisely because political concepts are so complex that the history of political thought is in such rude health?