The first volume of Richard Carlile’s periodical The Republican. Bodleian Library: Johnson e.3662 Photograph by Alex Plane, courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries.

On Friday 27 August, 1819, there appeared the first issue of a journal entitled The Republican edited by Richard Carlile. Its publication was a direct response to the Peterloo Massacre that had occurred just under two weeks before. Despite the header declaring it to be 'No. 1. Vol. I.', this was not, in fact, an entirely new journal but, as the editorial explained, the continuation of Sherwin's Weekly Political Register, which had been appearing for several years.

The change of title was, however, deliberate. Carlile was publicly identifying as a 'republican'. In his address to readers that prefaced the first volume he took pains to explain his understanding of the term. Noting that 'it has been the practice of ignorant or evil-minded persons' to associate republicanism purely with 'the horrors of the French Revolution' he urged his readers to look more closely at the etymology of the word. A republican government, he explained, is one 'which consults the public interest - the interest of the whole people' (The Republican, I, 'To the Readers of the Republican'). This, as I have argued in a previous blogpost, accorded with the traditional understanding of the term dating right back to ancient times. Yet, because Carlile was writing in the early nineteenth century, he was well aware of the additional connection that had been forged between republicanism and anti-monarchism. He engaged directly with this point, arguing rather cleverly that: 'Although in almost all instances where governments have been denominated Republican, monarchy has been practically abolished; yet it does not argue the necessity of abolishing monarchy to establish a Republican government.' In truth, Carlile believed that securing government in the public interest required a proper system of representation and that if this were to be introduced the abolition of monarchy was likely to follow. Nevertheless, his understanding of the double meaning of 'republican', and his emphasis on establishing government in the public interest rather than simply abolishing the monarchy, indicates continuity with the longer history of English republican thought.

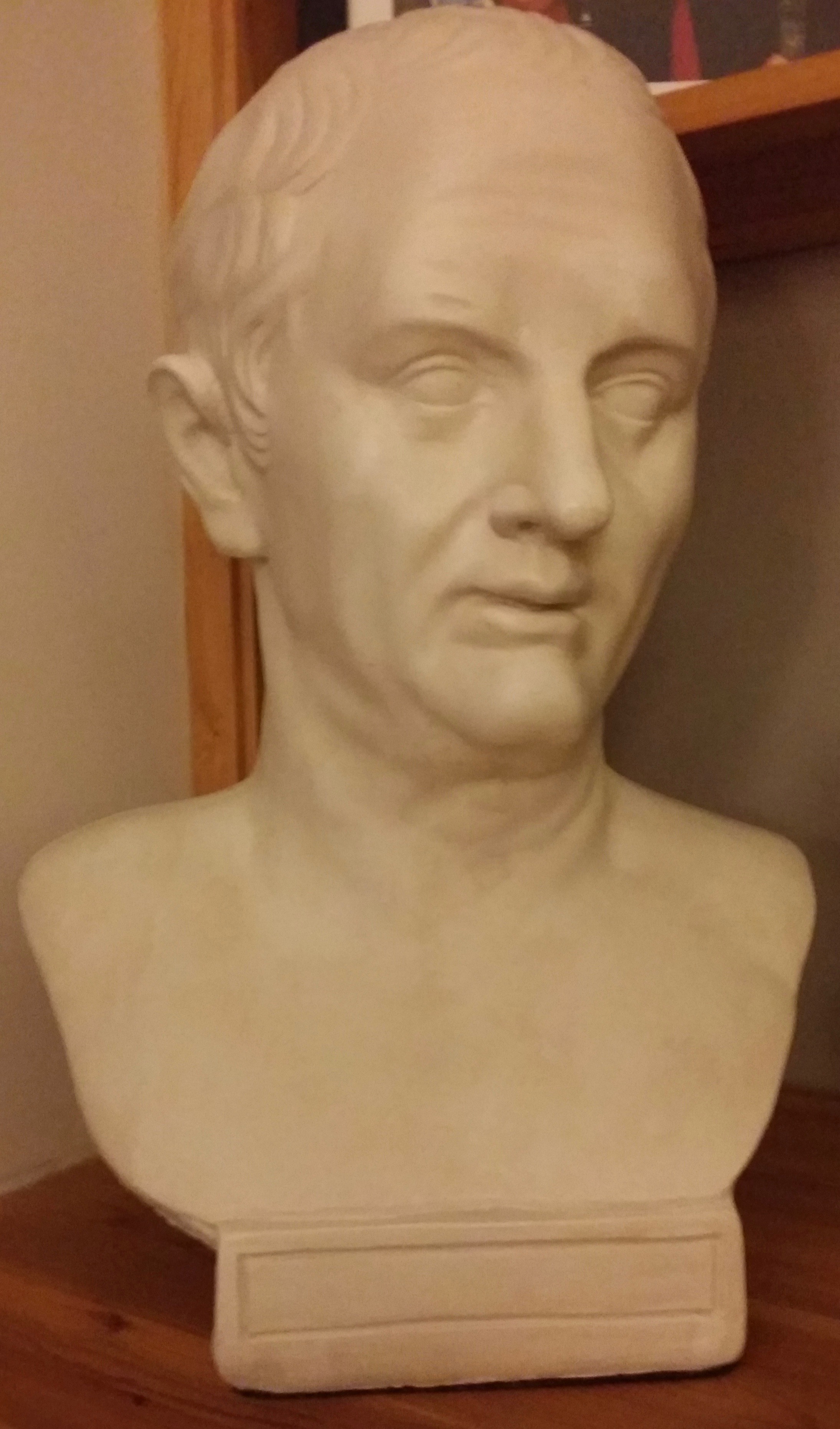

Thomas Paine by Laurent Dubos, c. 1791. National Portrait Gallery. NPG 6805. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

Carlile also associated his ideas more directly with those of earlier English republicans. He was a committed disciple of Thomas Paine and was responsible for printing and disseminating Paine's works. He was also an admirer of Thomas Spence, declaring that Spence's Land Plan was 'the most simple and most equitable system of society and government that can be imagined' and that it was 'a subject' about which it was 'worth thinking, worth talking, worth writing, worth printing' (Richard Carlile, Operative, 3 March 1839 as cited in Malcolm Chase, '"The Real Rights of Man": Thomas Spence, Paine and Chartism', in Rogers and Sippel (eds), Thomas Spence and His Legacy: Bicentennial Perspectives, special issue of Miranda 13 2016, pp. 3-4). Spence was himself a disciple of the seventeenth-century English republican James Harrington, and Carlile too made frequent reference in his writings back to the period of the Stuarts. He implied that the tyranny enacted by his own government at Peterloo and in its aftermath was similar to that performed by Charles I and his sons. In an open letter to the Prince Regent, which appeared in the second issue of The Republican, he warned the Prince that if he failed to deal justly with the perpetrators of the Peterloo massacre then 'the fate of Charles or James, is inevitably yours. And justly so.' (The Republican, No. 2 Vol. 1. 3 September 1819). Carlile also celebrated the heroic martyrs of the period, including John Hampden and Algernon Sidney.

Carlile repeatedly demonstrated his willingness to act as a martyr to liberty and to sacrifice his own personal freedom in the greater cause by stoically enduring repeated prison sentences. He was imprisoned for his role in publishing Paine’s works in 1819 soon after launching The Republican. This image was produced to celebrate his release six years later. ‘On his liberation after six years of imprisonment’ (Richard Carlile) by an unknown artist, 1825. National Portrait Gallery. NPG D8083. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

More substantively, The Republican echoed earlier English republican works in celebrating both civil and religious liberty, and in emphasising the interrelationship between the two. In the very first issue, Carlile explicitly declared his willingness to submit to martyrdom 'in the cause of liberty' and in the second issue he accused the despots of Europe of seeking to: 'abridge and destroy the liberties of their subjects, and to make their own authority absolute' (The Republican, No. 1 Vol. 1, 27 August 1819 and No. 2 Vol 1, 3 September 1819). Of particular importance to Carlile were the liberties of free speech and freedom of association. What was particularly galling about the Peterloo Massacre was that the individuals who had been killed had simply been enacting their right, under the British constitution, 'to assemble together for the purpose of deliberating upon public grievances as well as on the legal and constitutional means of obtaining redress' (The Republican, No. 5 Vol. 1, 24 September 1819). Such actions were necessary in Carlile's eyes because, like earlier British commonwealthmen, he believed that the British constitution had become corrupt and its balance disturbed. Echoing the late seventeenth-century thinker Henry Neville, Carlile argued that the balance of the constitution lay too much with the monarch and that too little power was wielded by the House of Commons. It had once dominated the other branches 'but that controul is quite destroyed, and through the influence of Boroughmongering, they are become the base and contemptible tools of every vicious faction that can get into power' (The Republican, No. 4 Vol. 1, 17 September 1819).

Richard Carlile, by an unknown artist. National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1435. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence.

Again like earlier English republican authors, Carlile was adamant that citizens should enjoy religious as well as political liberty. Echoing John Milton and other so-called 'godly republicans' of the mid-seventeenth century, he insisted on a clear and complete separation between church and state: 'I maintain on this head, that no government should legislate as to what shall or shall not be the religion of its subjects; or what differences should exist in their creeds' 'an established priesthood, of whatever tenets, is incompatible with civil liberty' (The Republican, I 'To the Readers of the Republican'). Yet in terms of his own personal religious convictions, Carlile had less in common with the 'godly republicans', instead taking the path previously developed by John Toland and his associates at the turn of the eighteenth century, whereby rabid anti-clericalism morphed into deism and even atheism. All forms of religion, Carlile declared, are 'an imposture and fraud practised by base and designing men on the credulous part of mankind' (The Republican, No. 2 Vol. 1, 3 September 1819). By publishing the controversial theological works of Paine, Carlile hoped to be able to emancipate minds from the slavish fears associated with Christianity (The Republican, No. 6 Vol. 1, 1 October 1819). Carlile's readers expressed similar views. In a letter that appeared in the second issue, Joseph Fitch of Old Road Academy, Stepney, praised Carlile for the patriotic firmness with which he faced tyranny after being charged with sedition for publishing the theological works of Paine. He urged those who saw the views voiced by Carlile as a threat to the state to stop being 'the voluntary dupes of priestcraft and corruption' and he ended by urging support for the cause of 'civil and religious liberty' (The Republican, No. 2 Vol. 1, 3 September 1819).

While the continuities between Carlile's understanding of republicanism and that of his predecessors are striking, he also introduced new elements. He was more critical than most earlier English republicans (with the exception of Spence) of the unjust inequalities between rich and poor. In issue six he attacked the 'Prince and Ministers, Sinecurists and Pensioners, Borough-mongers and Fundholders, Bishops and Parsons, Judges and Lawyers' for attacking the lower orders and seeking to keep them down (The Republican, No. 6, Vol. 1, 1 October 1819). He also championed the rights of other marginal groups within society, even asserting that women ought to be accorded political rights (The Republican, No. 5. Vol. 1, 24 September 1819).

Carlile's writings, and the continuity of his arguments with earlier English republicans, challenge the common assumption that the English have no sustained republican tradition. In fact, there is a rich and vibrant vein of republican thinking in this country, one that has been flexible enough to adapt to a variety of different circumstances and issues. The optimism and energy of Carlile's writings stemmed from his firm conviction that the unjust political system of his own day could be completely overturned if only the franchise were extended and the poor were given the vote. On this point history has proved Carlile wrong, which poses challenging questions for democratic republicans today.

![John Lilburne, England's New Chains Discovered, London, 1649. http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/leveller-tracts-6. 18.10.17. Taken from the Online Library of Liberty [http://oll.liberty.org] hosted by Liberty Fund, Inc.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57a64976d1758e28c2a46317/1508942506653-MC9ZTGQZPUPJNO70AQAP/Englandsnewchains.png)